| |

|

The

proposal to destroy the virus stocks caused many to reflect

upon the possibility of someone using the virus as a biological

weapon. Suspicions arose that certain governments or terrorist

groups may want--or already have--virulent strains of the

virus. Concerned individuals have voiced passionate resistance

to the destruction of the United States' stocks, arguing

that if others secretly kept the virus and developed it

as a biological weapon, we would be completely at their

mercy.

|

|

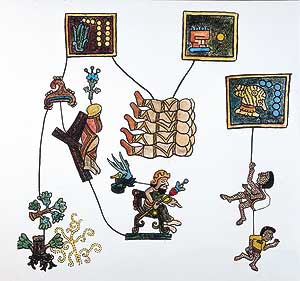

Aztec

victims of the smallpox epidemic of 1538 are coverd

with shrouds as two Indians, at right, lie dying:

Aztec drawing.

|

Some

scientists oppose destruction of the virus at a time when

so many new techniques have been developed for studying

mammalian viruses. They believe this step would cause a

tragic loss of information about many pathogenic viruses,

perhaps those that cause AIDS and hepatitis. Their arguments

are countered by

others

who point to the fact that the DNA of smallpox

has been sequenced and cloned, and that, even if the viruses

are destroyed, the cloned genes will be available for

research. Such counter arguments provoke heated comments

from those who would maintain the virus. "Anyone who says

the DNA sequence (of the genes) is enough doesn't understand

virology, and that includes some famous virologists,"

said one advocate of maintaining the virus. "To me, on

a scientific basis, we're taking an extremely precious

resource and destroying it...and destroying it ends the

whole issue ofpossibly understanding it in the future."

Henderson

has been an outspoken advocate in the argument to destroy

the smallpox vials. A professor at the Johns Hopkins School

of Public Health, he is the founder and director of the

Johns Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense Studies,

a think tank that considers what could be done to protect

Americans during a biological event or warfare.

In

1988, Henderson's organization put together a working

paper of deliberations regarding the destruction of the

virus. "The deliberate reintroduction of smallpox into

the population would be an international crime of unprecedented

proportions," he says. "Spreading of a highly lethal epidemic

in an essentially unprotected population, with limited

supplies of vaccine, no therapeutic drugs, and with shortages

of hospital beds suitable for patient isolation, is an

ominous specter."

The

paper concluded by concurring with the WHO resolution

to destroy the vials and encouraged readers to seek the

support of all concerned governments in carrying it out.

However,

arguments for keeping the virus carried the day, and on

April 22, 1999, President Clinton sought a delay in the

destruction of the stocks of virus based on a recommendation

of his advisors, reflecting agreement among all departments.

The president's message indicated that the research value

of keeping the virus and the uncertainty about who else

may have clandestine stores of it may have played a part

in his decision.

MORE QUESTIONS, FEW ANSWERS

Science,

politics, economics, ideologies, and ethics have come

crashing together as we grope toward a course of action.

There is too much we don't know or that we're not being

told. The WHO says it has about half a million doses of

vaccine and can produce more. Henderson estimates that

the stored vaccine supply in the United States might supply

about seven million doses. But these are pitifully small

numbers, and we don't know the quality of that vaccine

and how effective it would be in preventing infection.

One

argument for maintaining our virus stocks is that our

own supply might serve as a deterrent to potential aggressors.

As Henderson says, "There are those who believe that unless

it can be absolutely guaranteed that all stocks of virus

are destroyed, no action internationally could or should

be taken," a rationale similar to the nuclear deterrent

strategy that we have lived with for half a century.

"For

nuclear weapons, the argument may have a rationale," he

adds. "However, does a decision, for example, to destroy

all known stocks of smallpox virus in the USA without

assurance that Russia would do the same have comparable

implications? Does this suggest that if one country were

to use smallpox as a bioweapon that it would be the intent

of the USA to retaliate in kind? It seems unlikely."

Under

what circumstances, then, would we ever use a deterrent?

If the answer is none, then of what value is a deterrent?

What other purposes might there be in maintaining our

stocks?

If

we maintain stocks to continue research to perfect a new

vaccine or to unlock the secrets of viral pathogenicity,

a new series of questions arises. If these are meaningful

and realistic benefits--which some people believe them

to be--then it seems reasonable to ask whether these benefits

also appeared meaningful and realistic years ago, when

all but the two known remaining virus stocks were destroyed.

Assuming the same concerns were apparent then, we ask

what has been done

in the area of vaccine development in the last 20 years.

If there has been progress, we should know. If there has

been no effort, we must ask why.

If

work hasn't been done along these applied public health

lines, it could be that our policy makers see no value

in developing a vaccine for a disease that no longer

exists, which on the surface seems quite reasonable.

If so, what has been the value in maintaining any stocks

of virus for the last 25 years?

Henderson's

argument against the issue is clear: the smallpox virus

simply isn't needed to create more vaccines. "The smallpox

virus is a wholly different organism and has never been

used in vaccine development," he says. "Vaccines made

today would still be made from the vaccinia virus, which

provides a broad immunity that is effective against

all known strains of smallpox."

If,

he said, smallpox were to be released in a metropolitan

area, 100 to 135 million doses of the vaccine would

be made available--"enough to handle the need and not

create a panic situation." A standby facility would

be ready to produce 20 million more doses each month.

"With that amount we could feel confident that we're

covered in this country, and make the vaccine available

to other countries."

As

the June 1999 deadline for the destruction of the known

virus stocks approached, the World Health Assembly (the

highest governing body of the WHO) must have known that

the U.S. and Russia were far from agreement about destroying

them. Perhaps as a compromise, the Health Assembly amended

the WHO position to one advocating "temporary retention,

up to not later than 2002, for the purpose of further

international research." The recommendation was reaffirmed

by an international group of scientific and public health

experts meeting at WHO headquarters in December 1999.

Perhaps

it is impossible to eradicate any disease in the absolute

sense. Nobody knows how the smallpox virus originated.

There are, however, striking similarities between smallpox

virus and other primate viruses, suggesting an evolutionary

relationship. If the smallpox virus evolved as a human

pathogen some 10,000 years ago from, say, the milder

monkeypox virus, there is no reason to believe that

such an evolutionary event could happen only once. It

is difficult to imagine any microbial disease being

permanently eradicated, and Pasteur's dying message,

"The microbes will have the last word," takes on new

urgency.

The

thought that someone could earnestly consider using

the virus as a biological weapon deadens the spirit.

If that is the case, it makes little difference whether

or not we maintain our viral stores. The virus is not

our enemy; it is only a vehicle. Our future will not

be determined by whether or not we keep the virus, grow

the virus, mutate the virus. Our hope is in the gossamer

connection between our minds, our hearts, our music,

our philosophy, our science, our courage, our dreams.

All these are parts of the fabric of our lives. Nothing

is separate. The poet Roethke summed it up in a few

words, saying,

"...And

everything comes to one,

As

we dance on, dance on, dance on."

Richard

Levin is a professor of biology at Oberlin.

|