|

|

|

Whatever Happened to Religion On Campus? Everything! by Michele Lesie |

|

It's easy to see, though, why a non-religious student might have that impression. While colleges across the country are building multi-faith prayer centers, adding chaplains, removing Christian symbols from their chapels, and dismantling pews to make room for prayer rugs, Oberlin is holding back. The administration is not indifferent; just unsure. The devout here have been quiet, and largely uncomplaining. No one can say yet where this relatively recent phenomenon--an intense interest not just in "spirituality" (a buzzword these days, many students agree) but in the rituals of traditional faith--will lead. Or what students want, if anything, to change. "A part of this is a reaction to something that ended in the mid-'70s, the hyper-rationalism that all religions suffered from," said Rabbi Shimon Brand, the Jewish chaplain. "Everything had to be rational and empirical. I think one strand of the word spiritual is re-owning the experience of religiosity." The chaplains' office in Wilder Hall has long been the place for comfortable discussion of personal concerns for students in the Big Three, as the chaplains jokingly call their Protestant, Jewish, and Catholic realm, as well as for those who practice Oberlin's underrepresented faiths. As most college chaplains do, they deal with youthful resistance to the limitations that all religions come with: "I don't want to be categorized." "I feel closer to God walking in the woods." And the very popular, "I'm not religious, but I'm spiritual." So the shift toward expressing faith, which includes a desire among students to understand and practice rituals their own parents let slide, took the chaplains by surprise. "Some of them are flipping back to the spiritual forms of their grandparents," said Catholic chaplain Father Edward Kordas, who was startled one day by a student kneeling in church saying the rosary. Another student told him she was "nostalgic" for the Latin Mass. When Kordas tried to explain that nostalgic was probably not the right word (Masses have been celebrated in English for 35 years), the young woman said, "It's my family heritage." "They keep asking me extremely basic questions," said Kordas. "Why do we have the Stations of the Cross? Where does the structure of the Mass come from? Why are we particularly devoted to certain saints?" Lassen,

too, said he's seeing fewer and fewer students arriving

without knowledge of the Bible and their own traditions.

The students he advises are eager to learn, but, with

the exception of deeply religious Pentecostals and Evangelical

Christians--and yes, Oberlin has them--most continue to

shun categorization. "I don't think they know what the

categories are," he said.

"The Jewish community is slightly different," said Brand, whose students' choice of a subdivision is confined to the categories within Judaism. "What I'm seeing now is a desperation for religious experience. It's not political. It's much more internal and personal." Brand is hesitant to call the resurgence of faith among young people a mere trend. "If it is," he said, smiling, "it's 10,000 years old." Oberlin has always attracted more than its share of foreign students, for whom switching faiths or disowning religious rituals is out of the question. A high-school applicant from Taiwan, aware of the College's secular reputation, told Brand, "I'm wondering if I can survive there." Whatever

the reason, this revival of sorts has not gone unnoticed,

especially among students who practice, or would like

to practice, openly and comfortably. The campus religious

organizations

report increased attendance at services, more participation

in events, and more seekers and samplers.

Some say the faith has always been there, but in the last two years or so has simply become more visible, partly because the weary devout see no reason to hide their devotion in an institution that prides itself on embracing diversity. "It's a well-hidden secret that there are religious students at Oberlin," said Erica Seager, a senior from California. "When I came here, I didn't think Oberlin could offer me as good a Jewish place as other schools. I was pleasantly surprised. "This is a multicultural environment that tries to protect students of any racial and ethnic background, sexuality, and gender. But into that rhetoric of acceptance, religious faith has not yet entered. It's really time to insert religion into Oberlin's open, pluralistic mode."

"I don't think we're as well-accepted as other religions," said senior Andrea Ahne of Illinois. "During my freshman year, someone asked me, 'If you're Catholic, why did you come to Oberlin?'" Another student, Jane, got tired of being "picked at" by an atheist classmate. ("He kept asking me how I can believe in God.") Her answer was to join the Newman Community. "I figured, if I have to keep defending my faith, I may as well start practicing it," she said. "I'd say my experience here caused me to grow strong," another student offered. "To defend your faith, you have to know about it, so I learned more." Kordas added, wryly, "I've always said Oberlin is one of the best places for Catholics to be." It would be wrong to suggest malice, or anything worse than misunderstanding, the students made clear. As Rabbi Brand put it, "What's the dirtiest word on this campus? Exclusion." Religious students of all faiths tend to support each other and would probably do so without the various "crossover" campus organizations such as Oberlin Christian Fellowship and the fledgling Oberlin Interfaith Community. "I have never encountered anyone from another faith who hasn't invited me to one of their services," Ahne said. "I'm openly Catholic, and I eat in the Kosher Co-op because I like the company and the food," said senior Criss Porterfield of Oregon. "And everybody there wished me happy Easter."

Throughout this age group's childhood, the Church's

focus was on building community and social relevance,

"which left less time for the basics," Kordas explained.

"This is happening all over the country, so I'm not

so surprised at their questions anymore. They just want

to know more about their own faith."

While no religion predominates, the college has a strong Jewish presence (about 25 to 30 percent of the student population) and a very active Hillel. In a sort of role reversal, these students have shouldered much of the job of making sure the school's liberal, pluralistic spirit is preserved while the dust of these new matters of faith settles. "There has always been spirituality here," said Erica Seager. "Ties to nature, service to others, people doing yoga. But definitely, in the last several years, there has been more interest in traditional religion and, along with that, an increasing desire of religions to work together." "The Oberlin Catholic community," she observed, "is very liberal and open to Oberlin ideals, but a lot of people feel institutions in general are a negative force. They're not trusted by the student body. That's just the way Oberlin is. What these people don't realize is that religious students don't fall into any particular mold. The Jewish community, for example, is a mix of the very observant who keep kosher, to people who describe themselves as secular Jews and don't believe in God," she said. On Friday nights, Jews and Muslims share the Sabbath meal in Talcott Hall. The Kosher Co-op prepares the food. Someone always reads from the Koran.

Jewish holiday services are held at Wilder. There is

no synagogue nearby, no special space on campus, and

not much griping about the fact. (At some schools, students

have campaigned for equal accommodations and refused

to meet even in symbol-stripped chapels on ideological

grounds).

"Things can get a little crowded, but I personally feel comfortable," Seager said. "Talcott is the only place available. Besides, there are logistical problems. We can't carry food (on the Sabbath) from one building to another." Muslim students also follow similar dietary restrictions, she said. Dining jointly just made sense. Being in the majority is odd, she added. "I didn't grow up in a Jewish community, so it was a big shift coming to a place where there are a lot of Jews. I wasn't as observant when I was younger as I am now, partly because of this community and this rabbi. Shimon is willing to meet students on whatever level they're on." Senior Morris Levin of Philadelphia had a like experience. "I became more observant here. Much more than my parents," whom, he admitted, view his devotion with some trepidation. "The Jewish community here has always been strong, but recently, among the people I know, I've encountered a search for spirituality, a yearning. It's almost as though people are having everyday experiences that we don't have language for. Even so," added Levin, who got a laugh this spring when he prayed to "God, who may or may not be in heaven" before a sporting event, "it's still more OK to be a cultural Jew here, or an ethnic Jew, than to be a religious Jew." |

The

gravely polite young woman went out of her way to walk

a visitor to Fairchild Chapel, which, for an hour on Sunday

mornings, becomes a Catholic space. "Well, this is it,"

she said, pausing on the stocky structure's steps. Muted

pre-mass strains started up behind the chapel's heavy

wood door. The student turned to go, then commented without

preamble, "so many churches for such a non-religious school."

She is wrong. The college owns two nondenominational chapels.

The churches on or near campus belong to the community.

And despite what the school's protestant chaplain, Rev.

Fred Lassen, calls "a mythology of militant secularism,"

those in the loop know that Oberlin is not an entirely

temporal institution.

The

gravely polite young woman went out of her way to walk

a visitor to Fairchild Chapel, which, for an hour on Sunday

mornings, becomes a Catholic space. "Well, this is it,"

she said, pausing on the stocky structure's steps. Muted

pre-mass strains started up behind the chapel's heavy

wood door. The student turned to go, then commented without

preamble, "so many churches for such a non-religious school."

She is wrong. The college owns two nondenominational chapels.

The churches on or near campus belong to the community.

And despite what the school's protestant chaplain, Rev.

Fred Lassen, calls "a mythology of militant secularism,"

those in the loop know that Oberlin is not an entirely

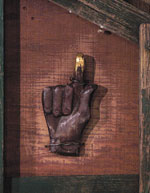

temporal institution. AFTER

SUNDAY MASS, "FATHER ED" AND A GROUP OF CATHOLIC STUDENTS

MET for their customary pizza in the Religious Life

Center at Lewis House. The Mass had been what one student

termed "Oberlin-specific." The school name is often

used as an adjective--Oberlinesque, Oberlin-y--and everyone

knows what is meant. In this case: no crosses, no kneelers,

and a plain dais in place of the altar, where Kordas

celebrated the Eucharist surrounded by students holding

hands. Those uncomfortable with the deviation remained

in the pews.

AFTER

SUNDAY MASS, "FATHER ED" AND A GROUP OF CATHOLIC STUDENTS

MET for their customary pizza in the Religious Life

Center at Lewis House. The Mass had been what one student

termed "Oberlin-specific." The school name is often

used as an adjective--Oberlinesque, Oberlin-y--and everyone

knows what is meant. In this case: no crosses, no kneelers,

and a plain dais in place of the altar, where Kordas

celebrated the Eucharist surrounded by students holding

hands. Those uncomfortable with the deviation remained

in the pews.