Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2007 Vol. 102 No. 3

Eating Fresh

Even during the colder months, locally grown vegetables are a staple in Oberlin’s dining halls, thanks to a grant from the College’s food service provider that helped erect a second greenhouse at George Jones Farm. The result? High-quality produce that takes just pennies to transport.

Even during the colder months, locally grown vegetables are a staple in Oberlin’s dining halls, thanks to a grant from the College’s food service provider that helped erect a second greenhouse at George Jones Farm. The result? High-quality produce that takes just pennies to transport.

Tastes great, less fueling—locally grown food is now a campus staple.

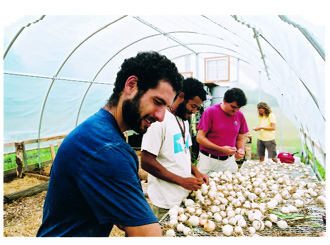

Late last fall, after the first frost called an official end to the growing season in Northeast Ohio, Obies Sara Waterman ’04 and Aaron Englander ’06 entered a greenhouse on the grounds of the George Jones Farm in Oberlin and harvested several species of organically grown leaf lettuce. Within 24 hours, the lettuce had taken its place on a dining hall salad bar—next to locally grown tomatoes—as part of a meal that also offered locally produced chicken and tofu, apples, honey, cheese, and milk.

Just seven years ago, less than 5 percent of the milk, meat, and produce served on campus was grown locally. But since 2001, when Oberlin selected Bon Appétit Management Company as its food service provider, that percentage has increased each year. The 35 percent target for 2007 represents more than a quarter of a million dollars of food spending in the local economy.

“We believe [locally procured food] is of a higher quality, supports the local economy directly, and is better for the environment because of its energy savings,” says Michelle Gross, director of Residential Education and Dining Business Services. “When you buy locally you don’t package as much; you don’t transport as much; and you don’t process as much.”

Every dollar spent by the College on local food generates between $1.96 and $3.20 in the local economy, according to a study conducted by environmental studies professor David Orr—proving that a commitment to local produce can have a meaningful impact on the economic health of this still-rural region. “Some local farmers don’t think it’s viable anymore to farm,” says Rick Panfil, general manager of Campus Dining Services. “We’re trying to help them see there is a market for local produce.”

Last spring, the California-based Bon Appétit took the unprecedented step of donating $6,200 toward a greenhouse in Oberlin that extends the growing season for organic produce grown on the George Jones Farm. The grant also helped purchase a waste oil furnace, which burns used cooking oils to heat the greenhouse—allowing the farm to start seedlings earlier in the spring and grow lettuce throughout the fall and winter. Of the 73 colleges and universities that utilize Bon Appétit, only Oberlin has earned such a financial boost.

“This is the first time Bon Appétit has made a cash investment in the production side of sustainable farming,” Panfil says. “We believe this may be the first direct collaboration of this kind between a food service company and a farm.”

The message for local farmers is clear: There is a significant market for local produce, and an investment of $10,000 or less can extend the growing season substantially. “The company took its commitment to buying local food one step further with the greenhouse,” says Brad Masi ’93, executive director of the New Agrarian Center, the non-profit organization that manages the farm. Soon, Oberlin-grown greens will be on the table at another Bon Appétit client: Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

“The commitment to the local farmer and other local entrepreneurs was one of the things Bon Appétit had been pressing for several years,” says Randy De Mers, the company’s regional manager. “Oberlin represented a location where the potential to take that to new levels was waiting.”

Student Feedback Spurs Change

Oberlin’s desire to buy local was not the only factor in selecting a new food service provider six years ago. Student complaints about food quality were on the rise, and Sodexho, the enormous conglomerate that had provided food service on campus for the previous 15 years, was seen as inflexible in the face of requests to alter recipes to meet student preferences, especially in vegan and vegetarian dining. But it was a factor quite distant from the campus that finally pushed the College to search for a new food service provider. In 1999, Oberlin’s students joined college students around the nation in protesting the investment of Sodexho’s European owners in for-profit prison management companies. For Oberlin students, it was time for Sodexho to go.

In selecting a new food service provider, the College evaluated such things as a company’s willingness to cook fresh food from scratch, to take vegan and vegetarian cuisine seriously, and to respond to student feedback. But also important were two factors related to minimizing the negative impact and maximizing the positive impact of generating 900,000 meals each year: resource reduction—that is, making good decisions regarding packaging—and a commitment and ability to work with local vendors.

As a company whose mission statement includes “creating food that is alive with flavor and nutrition, prepared from scratch using authentic ingredients … in a socially responsible manner for the well being of our guests, communities and the environment,” Bon Appétit easily caught the attention of the selection committee.

“Bon Appétit was one of the few companies that actually understood and had a program incorporating efforts to buy local,” says Gross. “Farm to Fork [the company’s name for its efforts to emphasize locally grown foods] was in an infancy stage back then, but at least they’d thought about it. They’d established a program and were embarking on it.”

Bon Appétit and the College agreed to an initial goal of making 10 percent of all food purchases from local sources. Apples, lettuce, and tomatoes were soon joined by local cheese, tofu, milk, honey, and chicken. Gross, who meets annually with De Mers to set goals for local purchasing, has been impressed with the company’s creativity and commitment to buying locally. “They have become a wonderful partner,” she says. “They’re coming up with ideas about as fast as I can.”

Of course, a commitment to local food alone would be insufficient. The food and service have to be good. And they are. Student reviews of the food are positive, and Bon Appétit has shown itself to be quite flexible in adjusting menus and recipes in response to student feedback. Just last fall, Oberlin was named by PETA as the sixth most “vegetarian-friendly” college in the country.

“There is a huge difference in the quality of food,” says Waterman, whose undergraduate years spanned the transition to Bon Appétit. She’s especially impressed with DeCafe, the Wilder Hall convenience store managed by Director of Retail Food Services Gina Fusco. “Every year you see that Gina has more and more local foods—foods from small, local producers,” says Waterman.

Beyond the benefit to regional economic health that comes from Oberlin’s increasing commitment to buying local is an educational purpose. Through such activities as the Eat Local Challenge, a lunch sponsored periodically by Bon Appétit prepared exclusively with ingredients from farms within a 150-mile radius of campus (shrimp was on the menu last fall), the dining hall becomes a classroom: a place to study sustainable consumption and stewardship of the earth. “I know that food that’s coming from far away may have a lower dollar sign on it, but it’s more expensive for my community,” says Waterman. “The simple act of eating can have a huge impact on social and political understanding on our campus.”

And the lessons to be learned from making a commitment to sustainable practices extend well beyond the perimeter of the college campus. “When demand changes, companies change,” notes Gross. “Even our larger, more corporate purveyors know we want more local, and they are buying it.”

Bon Appétit’s Randy De Mers calls Oberlin College “the standard bearer of where sustainability is moving” among his accounts. “I send people to Oberlin frequently and use the [food service] team and site as an active learning lab for managers,” he says.

Tim Tibbitts is a writer in Shaker Heights, Ohio, and a frequent contribtor to OAM.