Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2011-2012 Vol. 107 No. 1

’

Rethinking Teaching

Research about how people learn has changed the way Oberlin professors teach.

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

Nancy Darling points to an Excel table of different-colored squares scattered on her computer screen. "This, believe it or not, is high school sex," says Darling, a professor of psychology at Oberlin for seven years.

The dark blue squares indicate high school students who are not sexually active. Several shades of green indicate kids with different probabilities of having sex with their peers. The arrangement of differently colored squares can change dramatically from model to model — there can be schools where sexual activity is very low and some where it’s very high — but Darling is showing the Oberlin students in her adolescent development seminar how social issues can be examined using computational models, in which the variables can be considered mathematically.

The blocks of color start to shift when you drop one kid with a sexually transmitted disease — a dangerously red block — into the model. As her students watch the affliction spread, especially in the models where sexual activity is so high that everyone in the high school eventually contracts the disease, Darling can hear gasps and groans spreading throughout her classroom.

"A lot of my students will go on to work in social service agencies," Darling explains. "They’ll get into deliberations similar to the one this model addresses, which is how best to slow the spread of STDs in high schools when you have a limited program budget. People usually just sit around and argue about how to do it, but another approach is to create these ‘what-if’ scenarios through computational modeling and turn those arguments into numbers. Someone might say such-and-such program would work better, but the model helps you understand exactly how much better."

Only a few years ago, Darling wouldn’t have considered using computational models in her classes. She’s a statistician used to working with mathematical models that use hard data, so she wasn’t even comfortable using these what-if models herself. But she’s open to changing what she does in the classroom to help her students learn. She and several other professors — Richard Salter (computer science), Dan Stinebring (astronomy and physics), Michael Loose (neuroscience), and Ellis Tallman (economics), as well as Albert Borroni (computer support for teaching) — began to discuss how learning about computer modeling would equip students to grapple with many of the most complicated issues in the world.

"Almost every policy debate is based on computational models," Darling says. "Climate change, the Wall Street meltdown, stimulus packages, health care reform — these are all approached using models. If you want to participate in the debates, you have to understand modeling."

Stinebring and Salter held a conference on computational modeling five years ago. Two years after that, the group applied for and won a National Science Foundation grant to introduce computational modeling into courses throughout the curriculum. For three years, workshops were offered to teach this approach to faculty.

Now, the method is used in psychology, sociology, economics, geology, astronomy, political science, biology, neuroscience, and environmental studies. The overall goal is to introduce 85 percent of Oberlin’s students to computational modeling, with the assumption that students will likely take two different classes over the course of their studies and see how the approach can be used in different disciplines.

A Devotion to Pedagogy

Introducing computational modeling to the humanities is one of many ways that Oberlin professors push pedagogical innovation into the classroom. While many started teaching when the archetype of a great professor was the brilliant lecturer, they’ve been paying attention to research that smashes that archetype. The research shows that students learn better when they’re actively involved in working with the material—and that they learn best when they partner with other students to shape and question it. Learning also thrives when teachers reach across disciplines and use unexpected tools, resources, and settings. And—not so surprising—students learn when they nail down their understanding in prose.

The implications of this research are pushing many professors to change the way they work, so much so that alumni who took their classes even five years ago would be surprised. "It’s striking how engaged the faculty are in reflecting on their teaching and how they constantly revise it and add new elements," says Sean Decatur, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. "On an individual level, there are some who decide they want to try something new. Groups of faculty also get together to explore and discuss new pedagogical practices. Our office funds and supports many of these efforts."

History professor Steven Volk has been teaching at Oberlin for 26 years, and he’s led many of the efforts to explore and test new pedagogical models. Fifteen years ago, he began engaging other faculty members in this exploration, with initiatives such as Friday brown-bag lunches in which faculty discussed teaching approaches. Four years ago, he institutionalized this effort by founding the Center for Teaching Innovation and Excellence, which is housed in Mudd Library.

"There’s a fundamental revolution going on in pedagogy, where we’ve moved from teaching to learning," says Volk, who in 2011 was Oberlin’s first teacher to receive the U.S. Professor of the Year award (see sidebar). "We know that the way students learn best is to construct knowledge in their own heads. If I’m doing all the work constructing a beautiful lecture and all I want is for them to take it down, then they’re not constructing knowledge. So I’ve totally changed my classes to put student learning at the center."

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

For one thing, Volk no longer delivers the traditional classroom lecture. Instead, he prepares 30- to 40-minute video lectures that students view outside the classroom, at their own pace. Volk then breaks them into groups to discuss and answer questions about the material. "On the first day of class, I talk to them about wanting to create a community of learners, and that I want them to learn from each other as well as from me," he says. "I talk to them about their responsibilities within that community. As a result, discussions aren’t seen as wasted time between the nuggets of truth I’m delivering to the class."

Volk doesn’t expect his students to recall all the details they’ve discussed in class — after all, they have smart phones if they need to know that Bolivia’s independence from Spain took hold in 1825. He approaches his classes with what he calls the "backward planning" hypothetical. "If I bump into one of my students 10 years after graduation, what do I want them to remember?" he says. "Not the details, but the concepts and the learning skills: how to investigate, read closely, analyze, interpret, and work with others."

Breaking Boundaries

One of the pedagogical ideas Volk has embraced is called "languages across the curriculum." He augments his two-semester course on the history of Latin America with an extra hour per week taught in Spanish for students who want to study the culture more intensively and earn an extra credit.

"If you want to study a part of the world where English is not the main language, it makes sense to do some studying in the language of that country," says Sebastiaan Faber, a professor of Hispanic studies who has organized faculty workshops on the subject. "To understand the history, you have to know the language so you can talk to sources and read documents. So many nuances are lost in translation. The kids doing the extra hour come to class with insights that the main class doesn’t."

The concept was first introduced across the country in the 1980s, Faber notes, and has recently come to the fore again because of a renewed interest in internationalism. It’s a concept that has great potential at Oberlin where there is a strong international faculty—many professors either grew up speaking the language of the country they teach about or learned it as scholars. "We have experts in French history, Latin American history, Asian history, Eastern European history, and Russian history, and all those people as a matter of course speak and read the languages of the region," Faber says. "This program allows the faculty to make fuller use of the skills they have as scholars."

For instance, Ari Sammartino, associate professor of history, will be teaching a course about Weimar Germany and will include an extra session taught in German. As she’s not trained to teach German, a professor in the German department will help her prepare that session. "It really makes sense for an expert in German history to work with the German department," says Faber. "This new effort breaks down barriers between departments that don’t make sense."

While there was never a barrier to enter the Allen Memorial Art Museum, it’s only in the last decade or so that a significant number of faculty members have recognized that its rich collection can be as rewarding academically as it is aesthetically. The museum received a $1.25 million challenge grant from the Mellon Foundation in 2008 to spur greater use of its collection in teaching. The grant helped establish a permanent endowment for the museum’s Office of Academic Programs, which is curated by Liliana Milkova.

"My role is to facilitate the use of the collection as a teaching tool and the galleries as a learning site," says Milkova, who has held workshops with faculty to talk about pedagogical opportunities that the museum offers and works with about six classes each week. "I do a lot of outreach to non-art faculty who are often hesitant to integrate art into their teaching. I want them to think of the art as a learning tool, not some esoteric material. We can find the meeting point between their discipline and the art."

"If I bump into one of my students 10 years after graduation, what do I want them to remember? Not the details, but the concepts and the learning skills: how to investigate, read closely, analyze, interpret, and work with others."

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

In a recent use of the museum’s collection, Milkova led a session with Carol Lasser’s advanced history seminar in second-wave feminism to see how the ideas from the movement were expressed in art.* One of the signature pieces was a still life painted by Audrey Flack in 1974 called Strawberry Tart Supreme, which depicts a tray of desserts with a dripping, glistening strawberry tart at the center. "Traditionally, women weren’t considered advanced enough to create anything more intellectually engaging than still lifes," Milkova says. The artist was using the still life genre and the focus on baking—a traditional women’s pursuit—to challenge these constraints while hinting at the intensity and even ferocity of women’s desires.

Taylor Allen, associate professor of biology, has also been working with Milkova to wrench his students’ learning out of the traditional framework. For his Biology of Love class, his students view about 15 works of art that depict some aspect of love, then break into groups to develop an argument based on their visual analysis — for instance, that love is depicted differently in the west than in the east, or whether the artists’ depiction of romantic love concurs with the scientific understanding of love. "One thing I like about this is that it puts the students in the realm of uncertainty," Allen says. "Science students always feel there is one right answer, but in art there isn’t one right answer."

The students learn to hone their powers of visual analysis, assisted by Milkova as she explains how she as an art historian approaches the work. The ability to conduct a vigorous visual analysis serves students well when they begin working with microscopes. In fact, a few medical schools take a similar approach with their students, believing that the skills they learn in the museum will buttress the visual acuity they need to examine patients.

"When you take students who are primarily focused on making and performing music into a visual setting, they respond quickly and eloquently to it."

And not so surprisingly, the visual richness of the museum can stimulate richness in other art forms. At least, this has been the experience for Peter Swendsen ’99, assistant professor of TIMARA (Technology in Music and Related Arts). As soon as he began teaching five years ago, he took his students into the museum, and now it’s a regular part of his teaching.

A recent example is the class he cotaught with Nick Jones of the English department called Landscape Soundscape Wordscape, which explored how artists in all media start with the idea of a place and translate that into different creative forms. Students examined landscape paintings, musical compositions, poetry, and other works, and also made their own work.

"When you take students who are primarily focused on making and performing music into a visual setting, they respond quickly and eloquently to it," Swendsen says. "You need to have things about which to write your music — you need starting points that aren’t just other music — and the museum consistently supplies starting points."

He doesn’t often think of this kind of teaching as innovative; it’s just something that often happens at Oberlin. "But as soon as I talk to people at other campuses, the perception of this being innovative just goes through the roof," he says. "I don’t think a lot of this creative mixing is going on in the world at large."

Reinforcing the Power of Language

Another kind of creative mixing is taking place on campus as Oberlin puts more effort into ensuring that students in all disciplines become good writers. Oberlin has pursued "writing across the curriculum" since 1984, but some felt the approach didn’t encourage writing proficiency strongly enough. "For instance, we’d have a history class that had a writing designation, so the students knew they’d have to write a paper there," says composition and rhetoric professor Laurie McMillin. "But there was nothing in the designation that required the teacher to really work with them on how to write the paper, how to revise, and so on. If we care about student writing, then we need to be more engaged with the process."

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

photo courtesy of Oberlin College Office of Communications

McMillin is helping guide a transformation that will come to fruition in the fall of 2013. In addition to the writing instruction that takes place in the first-year seminar all new students are encouraged to take, other classes spread across the disciplines will be designated as writing intensive or writing advanced. The professors will train to work with students on their writing: McMillin has already conducted workshops for faculty members — in science and social science, so far — who might be unsure about their ability to teach writing and concerned that the time spent on writing proficiency will take away time they need to teach their subject. McMillin says that once they try it, they’re often relieved on both counts.

"I had a young history teacher, Marko Dumancic, take the workshop," she says. "He reported back that he had the students do lots of writing and that it really helped them learn the content."

The ability to write within and outside their disciplines will stand the students in good stead through their years in higher education and beyond. "We have kids working on such interesting things," says McMillin. "They need to be able to communicate that to other people, not just other specialists."

A Culture of Risk Taking

That many of the same emphases and innovations have enlivened the conservatory is a testament to the importance of the barrier breaking that drives these changes.

"We were very compartmentalized before," says the conservatory’s dean, David Stull ’89, who is in a position to know since he was a student at the conservatory more than two decades ago. "What used to happen was students would go to theory and history classes and find there wasn’t a connection between those classes and performance." Now, with classes such as Performance and Analysis, there is a bridge between those realms. The result is that the intellectual exploration that takes place bolsters the students’ ability to meet the ever-changing demands of careers in music.

Brian Alegant, professor of music theory and director of the division of music theory, says the conservatory faculty has moved toward a model of more active learning and engagement with the students.

"The whole idea for me is to put the student in charge of his or her own learning," Alegant says.

Gone from Alegant’s class are midterm and final exams. "Everything is projects based," he says. And while student assignments in the past were based on a piece of music dictated by the instructor, Alegant wants his students to choose. "If you’re a bassoon player, what the [heck] do you want to work on a Schubert piano sonata for?" he says. "Why don’t we choose a piece that you’re currently learning?" Not only do students choose their inputs, they choose their outputs, as well. "You might write a paper, or you might do a recording, or you might compare and contrast different performances, or you might create an analytical diagram, or you might decide that you want your final project to be an article that you’re going to submit to Horn Call, or to Violin Quarterly, or Piano Quarterly, so you can actually take a stab at getting into the professional world of publication."

Conservatory teaching is also moving away from what Alegant characterizes as the "I am Delphic Oracle, holder of all knowledge" model, "toward the idea the professor is merely a facilitator in the student’s educational experience." That also means moving toward alternative grading schemes and a tremendous amount of self-reflection. At midterms and finals, he asks students for two pages of reflections, one page — "no BS" —about what they learned, and another stating what grade they deserve, and why. Most of the time, he says, they’re right on the mark.

The conservatory is also marshaling technological advances to meet the students where they are. While the faculty members want students to listen to music and read scores as much as possible, until recently, that material was mostly available in the library. But, Alegant says, "Most musicians lead vampire hours." So the conservatory digitized scores and sound files so students can access them on their own schedule.

Like the college, the conservatory is stressing the importance of writing for students, even those planning careers in performance. The market for musicians and artists demands that students become malleable and draw broadly from a range of skills. "You have to think, you have to speak, and you have to write," Alegant says.

The conservatory is so committed to encouraging written communication, it has created a music criticism competition that brought in some of the biggest reviewers in music journalism, and awarded cash prizes for the best reviewers. The Stephen and Cynthia Rubin Institute for Music Criticism will be a biennial competition at Oberlin.

Conservatory students are also encouraged to take advantage of the opportunities of the Creativity & Leadership Project, which funds student-led entrepreneurial initiatives. The project has supported concert tours of student musicians presenting new music on the East Coast, chamber music and jazz in Italy, and a classical guitar and classical saxophone duo in a number of university towns.

The entrepreneurial impulse that is encouraged is part of an over-arching culture at the conservatory that encourages risk taking, partly the result of who teaches here and who comes here as students. "We tend to attract, and then we nurture and cultivate, students who are interested in taking these types of risks," says Alegant.

Nowhere is that risk taking more evident than with the conservatory’s emphasis on new music, inside and outside the classroom. Students have opportunities to perform, compose, and record, on their own and with the Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble, headed by Timothy Weiss, director of the division of conducting and ensembles and professor of conducting.

"When you’re doing a new piece, it’s impossible to have a series of opinions about how it should sound," Dean Stull says. "There isn’t a history of debate on what the work is all about." Freed from the constraints of custom and expectation, students can work out their own ideas about the piece. When students return to the canon, Dean Stull says they find something interesting has happened: Their contemporary music explorations have created a fresh perspective on the works with which they’ve long been familiar.

"By developing a culture around new music, you actually cause the performance of all music to be raised dramatically because of the skills the students take away from those experiences," Stull says.

"When they go back to, say, the Beethoven quartets, they’re far more willing to just look at the score—just stare at it—and say, ’wait a minute—maybe we should do this instead.’ They have become open to new possibilities."

Pedagogical Gizmo Helps Change Class Dynamic

Students arrive in Dan Stinebring’s astronomy and physics classes and unload their backpacks: books, pads of paper, laptops, and clickers. Clickers? Are they competing to change TV channels?

Stinebring, the Francis D. Federighi Professor of Natural Science, talks briefly about the subject of the day, asks a question, then a screen lights up with four different answers. After some productive rumination, students across the room push a button on their clickers. Immediately, the technology provides the summary of their votes, and Stinebring has an instant understanding of the array of student comprehension. If the class is evenly divided between those who have the right answer and those who don’t, he tells students to turn and convince their neighbor that they’re right.

"It has a remarkable impact on the class," Stinebring says. "There’s a moment of chaos and hubbub with everyone talking to their neighbor, trying to put their reasoning into words. That articulation usually helps move the overall understanding along. This fits into what I’m trying to do with my students in general. I want active learning in the classroom, not the traditional passive learning, which treated the students like passive vessels that we pour knowledge into."

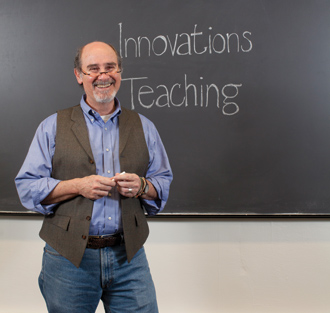

Steve Volk’s History of Innovation

photo by Tanya Rosen-Jones '97

photo by Tanya Rosen-Jones '97

Steve Volk pauses in the middle of a class discussion on dissension in Spain’s South American colonies. "Tupac Amaru was the last Incan emperor," says Volk, professor of history and chair of Latin American studies. "That’s where Tupac the singer took his name."

The students register an extra spark of interest, and then the discussion rolls on to the difference between a riot and rebellion.

Is Steve Volk an extraordinary teacher because he comes up with these snippets of information that knit the class material to the students’ extracurricular interests? Not really, but it’s part of the package.

As the recipient of the 2011 U.S. Professor of the Year, Volk sets an example for college teachers around the county. The award was created by the Council for Advancement and Support of Education and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. This is the only national program to recognize excellence in undergraduate teaching and mentoring. Volk also was awarded the American Historical Association’s Nancy Lyman Roelker Mentorship Award after being nominated by some of his former students.

Throughout his 26-year career, Volk has always been eager to try new approaches to teaching that will benefit his students. And he’s been a motor for pedagogical innovation on campus, helping to spread the latest research on student learning through brown-bag lunches and the founding of the Center for Teaching Innovation and Excellence.

In his eagerness to help students learn, he creates such fertile classroom discussion that he also learns new things. "I love teaching undergraduates," Volk says. "They’re not set in their disciplines, and they don’t know which questions they’re not supposed to ask. Often, those questions really open me up to something I hadn’t known or thought about before."

Kristin Ohlson is a freelance writer and author in Cleveland Heights. Jeff Hagan’86 contributed additional reporting.

*In the print version and an early online version, we erroneously said this was taught by Andrea Estepa. We regret the error.

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.