Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2014 Vol. 109 No. 1

Welcome to Cleveland!

A new wave of Oberlin alumni has hit the shores of Lake Erie.

By Jeff Hagan '86Photographs by Mika Johnson '01

Cream Rises Naomi Sable ‘02, Josh Rosen ‘01, and Ben Ezinga ’01 at the Fairmont Creamery, which they are redeveloping.

For developers Ben Ezinga ’01, Josh Rosen ’01, and Naomi Sabel ’02, the run-down husk of the former Fairmont Creamery at the edge of Cleveland’s forever-almost gentrifying Tremont neighborhood is where imagination and ambition meet opportunity.

Dried paint chips lose their tenuous grip on concrete and masonry walls as a wind whips through windowless frames. Tilted floors—once allowing dairy debris to wash down the drain—are a reminder of the building’s former working life. Still, the three alumni are smitten with this 106,000-square-foot mess. They’ve lined up $14.7 million in public and private investments to convert it into a hub of commercial enterprises and mixed-income residences. Sabel, pointing to a mushroom-shaped column top, says a bit rhapsodically, “We’re going to keep these. How cool will it be to have these in your living space?”

Gabe Pollack ‘10 at Cleveland's Nighttown jazz club, where he helps produce shows and manage artists.

The enthusiasm of this trio—whose company, Sustainable Community Associates, developed a block of East College Street in Oberlin—is matched by the enthusiasm of Cleveland civic and business leaders who knew them from their Oberlin work. Rosen says it’s not uncommon for him to get a 5 a.m. text from Cleveland Councilman Joe Cimperman asking, “What can I do for you today?”

“They’re so smart, and they have the ability to sell their ideas to people who don’t get them at first,” says Cimperman. These three “knew how to approach people and not be officious snobs. Maybe that’s the Oberlin touch—being kind but also kicking butt. Maybe it’s the idea of taking on projects that everyone says are impossible.”

It’s not just the young developers who see Cleveland flowing with milk and honey. A fresh, chance-taking spirit has settled on the place, and Oberlin folks have taken notice and are taking part. Most are drawn to the former steel town’s inexpensive real estate, rich cultural heritage, and thriving medical community. They’re also fond of its beer.

Downtown Cleveland.

As with the Fairmont Creamery, much of what’s new in Cleveland builds upon the best of what’s old. The city no longer hides the rusted roots of its industrial past. Its granddaddy microbrewery, Great Lakes, even brews Burning River Pale Ale, which name-checks the infamous 1969 river fire that left a scar many Clevelanders still feel.

“I always thought Cleveland had a certain majesty. But it was down at the heels for sure,” says retired advertising executive and art collector Fred Bidwell ’74. “Local low self-esteem was epidemic. That’s really changed. Cleveland now has some swagger and pride.”

The notion that smart and creative young people would choose to live in and celebrate tattered, former industrial cities like Cleveland even has a name: Rust Belt Chic.

“The term can be used both straight and ironically,” says Anne Trubek ’88, whose Rust Belt Chic Press publishes anthologies and the online magazine Belt. The term was coined in the 1980s by comic writer Joyce Brabner, widow of famed Cleveland comic book writer Harvey Pekar, to describe the attitude of New York hipsters coming to Cleveland to marvel at its urban decay.

While the term may be ambiguous, there’s no doubting that something has Oberlin graduates—long fast-tracked to hip cities on both coasts—taking longer looks at the increasingly funky city on a Great Lake.

The college itself encourages interaction with its bigger neighbor to the east. President Marvin Krislov has touted the sophistication of Cleveland’s restaurant scene in his weekly letter to the campus community. The Oberlin Business Scholars program, for the past 10 years, has connected students with alumni business leaders in Cleveland, along with those in New York, Chicago, and Washington. A semester-long intensive theater immersion with the edgy Cleveland Public Theatre, involving 16 students and five faculty members, culminated in a piece called Water Ways that earned rave reviews. Artist Corin Hewitt ’93 engaged a team of Oberlin students as part of his installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art in 2013.

Lila Leatherman ‘13 (Makillda) and Grace Kanaan ‘12 (Midnight Smack) of the Burning River Roller Girls league.

Many students and young alumni who live in Oberlin are drawn to Cleveland simply for the opportunities not available in town. Cuy Corey Patrick Harkins ’12, for example, a tutoring coordinator at Oberlin Community Services, manages the Cleveland-based Addicted to Glamour drag pageant system. Lila Leatherman ’13, a biology lab instructor at Oberlin, competes with the Burning River Roller Girls, the city’s roller derby league. Three nights a week, she treks to Cleveland’s eastern border for games and practices, where she’s known as Makillda. (“I haven’t laid anyone out yet,” she says hopefully.)

For many, though, the draw is specific to Cleveland. As a Burning River Roller Girl, Leatherman joins last year’s rookie-of-the-year Grace Kanaan ’12 (Midnight Smack), who is studying for a master’s degree in medical physiology at Case Western Reserve University and applying to medical schools. Kanaan hopes to stay put: “As an aspiring physician, Cleveland is a great place to be. University Hospital, MetroHealth, and, of course, the Cleveland Clinic are all nearby.”

Perhaps Jackie Mostow ’12 will be among Kanaan’s medical school classmates. Mostow moved to Cleveland after Oberlin to work as an executive assistant to civic leader Lee Fisher ’73. She is now preparing for med school and working for Neighborhood Family Practice, doing Affordable Care Act outreach and education. “I find myself in love with the community I have in Northeast Ohio,” she says.

The Transformer Station art space on Cleveland’s west side, created by Fred Bidwell ‘74 and Laura Bidwell.

Alicia Smith ’10 was a writer in Rochester, N.Y., with a master’s degree in journalism when she decided to go back to school. “I was interested in medical sociology and knew that Case was one of the few places that offered it.” Her boyfriend, David Tran ’10, a nurse, soon followed and now works at MetroHealth hospital.

The city holds special appeal for people interested in the not-very-lucrative field of the arts: Its arts organizations are easy to access, and the cost of living is low.

New Orleans native Taylor “Floy” Hoffman ’13 wrangled an internship with Fred Bidwell and his wife, Laura, whose west-side Transformer Station exhibition space serves as a satellite for the Cleveland Museum of Art. The Bidwells have connected Hoffman to other opportunities, including a paid gig at the Cleveland Museum of Art, helping with a pop-up installation called the Truth Booth. Like arts workers in many cities, Hoffman augments her income with shifts in retail and restaurants. Cleveland, she says, offers “low barriers to entry. I have access to things that as a 24-year-old recent college graduate I probably wouldn’t have somewhere else.”

Lora DiFranco ‘08 happily landed in Cleveland to work for an arts and planning organization.

Sharing a house with Hoffman is Frances Lee ’13, a painter who works part time at a tech company. “I like that I can support myself with a part-time job and have a large attic studio where I can spend a lot of time working,” she says.

To Lora DiFranco ’08, who works for LAND studio, a nonprofit that designs and programs public spaces around town, Cleveland “is the least pretentious place on Earth. It has all the benefits of a big city, but with a small-town feel. If you have energy and passion for an idea, people will be really supportive,” she says. “Even if your idea is a coloring book for adults, like mine was.”

With an eye toward opening his own jazz club, trumpet player Gabe Pollack ’10 shifted his studies at Oberlin to the conservatory’s Creativity & Leadership program his last year. These days he helps produce shows and manage artists at Cleveland’s Nighttown jazz club, gathering important experience along the way. “DIY-type people can live here cheaply and work on projects and not worry about how to pay the rent,” he says. There’s a market in Cleveland for a jazz club that caters to younger crowds with smaller budgets, he believes. “If I open up a venue in Cleveland, I’ll be here forever. And that’s not out of the question.”

Cleveland’s rich traditions in philanthropy, progressive politics, organized history—and intractable urban problems—are yet another draw for Oberlin grads, who are among the city’s Teach for America teachers, Refugee Response volunteers, political organizers, and social workers.

Therapist Syrea Thomas ‘11 cares for Cleveland’s children.

Therapist Syrea Thomas ‘11 cares for Cleveland’s children.Syrea Thomas ’11 earned a master’s degree in social work at Case’s Mandel School of Applied Social Science, where many of her requirements were met through real-world field placements. Her office as a school-based therapist is a trailer that sits behind an elementary school in a rough-edged neighborhood on the west side. And while she considered living in Chicago, she discovered Cleveland “offers a lot of mental health agencies, especially for children.”

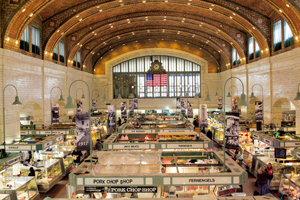

The majestic West Side Market,

a draw for student and alumni foodies alike.

The majestic West Side Market,

a draw for student and alumni foodies alike.To appeal to smart young people, however, a city needs more than a low cost of living. Obies enjoy places like the Happy Dog, a hot dog restaurant that hosts chamber concerts performed by Cleveland Orchestra musicians; the Ohio City Bicycle Coop; the indie-minded Beachland Ballroom; a steady stream of hip flea markets and craft fairs; and a foodie scene that includes the voluptuous West Side Market and a growing network of urban farms planted on formerly empty city lots. “I have found a lot of things I liked about Oberlin in this city,” says Lee.

“There are amenities attractive to somebody just out of school—such as a vibrant cultural and entertainment scene,” adds Bidwell. “You could go to San Francisco or Berkeley or Brooklyn—really hip places, but where everything is amazingly costly. You’re one of tens of thousands of people trying to find a place there. In Cleveland, you can make something happen and make a difference in a way that would be much more difficult in a bigger town.”

Graphic by Ryan Sprowl.

Graphic by Ryan Sprowl.

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.