|

| Home :: Features :: Lessons Learned on the Lost Highway Lessons Learned on the Lost Highway Story by Heidi Waleson. Photos by Steve J. Sherman ’81.

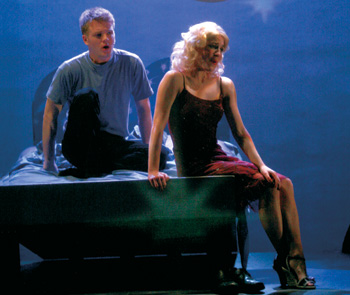

Last October, Raphael Sacks, a six-foot-four sophomore theater major, got the score for his first-ever opera role: the demented porn-king mobster Mr. Eddy in Olga Neuwirth’s Lost Highway. The part was “the most rhythmically complex music I’ve ever seen,” Sacks says. “I’m a singer and I’ve taken lots of theory, but this had constantly changing meter and subdivisions—any given beat could be in septuplets or in four. I had weekly coachings with Daniel Michalak, the Conservatory’s vocal coach and accompanist, but when I got to the orchestral rehearsals, I found that my big scene [in which he rages against a man for smoking in a garage] is mostly accompanied by a sextet—piano, guitar, bass clarinet, saxophone, trombone, percussion—all pushing the limits of their instruments to find sounds you’re not going to be able to find in a piano reduction.” Not only did Sacks have to synchronize his Sprechstimme tirade, with pitch approximations ranging from falsetto into low bass, with the orchestration, he was also supposed to be ferociously kicking someone to death at the same time.

Such were the challenges of the U.S. premiere of Lost Highway, a winter-term project mounted in Finney Chapel in February and then brought to New York for two sold-out performances at Columbia University’s Miller Theatre two weeks later. Lost Highway brought together acoustic musicians, electronics and computer experts, singers, composers, theater and dance artists, video producers, directors, a screenwriter, and many others in a Conservatory- and College-spanning collaboration that would be hard to imagine taking place anywhere else. “We’re made to do this,” says Lewis Nielson, Chair of the Composition Department and the project’s producer. As was the case with another winter-term endeavor, the historical performance Royer opera mounted in 2002, Oberlin is an ideal producer for such an unusual project as Lost Highway, since it is uniquely positioned to assemble the necessary resources—time, space, labor, and skills—as well as to assume the risk. Such endeavors relate clearly to the real world. Miller Theatre devotes about half of its season to contemporary music; it was George Steel, its Executive Director, who suggested the opera in the first place. And Newsday critic Justin Davidson wrote, “With this production, Oberlin has challenged other music schools to prepare their students for the weirdness of real musical life. Violinists can practice Paganini Caprices all day long, but when the time comes to accompany a grunt aria, will they know what to do?” A Long, Strange Trip

The attraction of Lost Highway for Oberlin stemmed from both its source material and the opera itself. The piece is based on the 1997 film by David Lynch, a nightmarish work in which a jazz musician, haunted by strange phenomena, appears to have murdered his wife. On death row, he transforms himself into another man and plunges once again into a mysterious journey, in which his wife reappears as another woman, who seduces him into situations in which he kills again. The viewer is never entirely sure what is happening. Lynch, long a cult hero (his other famous works include the films Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive and the television series Twin Peaks), has a significant fan base at Oberlin. Even more critically, Nielson and David H. Stull, Dean of the Conservatory, see Olga Neuwirth’s music, which combines acoustic instruments, amplification, electronics, and other media, as an unusually successful example of complex and unconventional contemporary composition. “This is the first time I’ve seen a composer effectively integrate so many media in such a large scale,” Stull says. “It’s an enormous sonic palette and visual palette, and it is seamless and purposeful, designed to underpin an artistic point of view. Whether you agree with it or not, it is most definitely about something.” The educational value of the project, they believed, would be huge.

The Austrian-born Neuwirth, 38, who studied with Tristan Murail, Luigi Nono, and Pierre Boulez, wrote Lost Highway for the Graz Festival in 2003. She and her co-librettist, the Nobel Prize-winning writer Elfriede Jelinek, drew their text almost verbatim from the film screenplay by Lynch and Barry Gifford. A Lynch fan from an early age, Neuwirth chose Lost Highway because, she says, “I’m fascinated and obsessed with recollection and memory, and how you can’t escape from your own past. For Fred [the musician protagonist who becomes Pete, a hapless young garage mechanic], what is real, and what is his imagination? These have been important topics for my music for years. Is it a sample or a live musician? Is the note treated or changed? What is real? What is fake? And of course, there are the time loops. How do we deal with things that are coming back, so that we can’t step out from them?” Although Neuwirth has written music for films, playing what she calls “the supporting role,” the Lost Highway film acted as an inspiration for something new. “I did an analysis of the whole film, frame by frame,” she says. “Then I had to forget the visual.” And while her text stays close to that of the film, she points out, “They are not talking a lot. They don’t give any real information. I reduce it even more, so that nothing is conveyed by language, so there is more space for the music.” The opera thus has a different kind of intensity. Instead of creating unease and dislocation through purely visual means, Neuwirth accomplishes those goals through sound. Audio Files

Producing Lost Highway involved numerous departments at Oberlin, another key aspect of the project’s appeal. All had to work in unusual ways. The orchestral players, from Asso-ciate Professor of Conducting Timothy Weiss’s Contemporary Music Ensemble, are amplified and their sonic environment is altered by electronics in real time and scordatura (de-tuning) in the score. It’s the sort of work these students like, Weiss says. “They are interested in getting their fingernails dirty with musical material that is out of the ordinary. They want to turn over every stone of detail to get what the composer wants.” Onstage, the performers—actors and singers who are also amplified and affected by sound processing—must whisper, speak, and sing in rhythm, sometimes with severely extended vocal techniques. In addition to his anti-smoking rant, for example, Mr. Eddy gets his throat cut and gags and gargles through his death throes; Fred’s transformation into Pete is accomplished with howls of agony from both the actor and the orchestra (what critic Davidson calls the “grunt aria”). Work began early on the piece’s complex requirements. In the summer of 2006, Leif Shackelford ’07 was hired to do the bulk of the computer programming for the sound design, overseen by Associate Professor of Computer Music and Digital Arts Tom Lopez ’89, who chairs the Technology in Music and the Related Arts Department (TIMARA). Lopez explains: “The composer provided us with about 100 samples—pre-recorded audio files of sound—that were incorporated into the overall design. The instrumentalists and singers also were processed live, with reverbs and delays, in real time. For example, in the moment after a grisly scene, the character Alice lets out a ‘Wow!’ We harmonize it so it sounds like multiple voices, which adds a little extra spice. Also, the audience is surrounded by about 20 loudspeakers, and there are sounds that move around the audience and the stage. All that coding had to happen beforehand.” Shackelford also helped incorporate changes made by the composer during the production process. Once casting was complete in the fall, Lopez and his team began working on the samples, redoing about half of them —“particularly those that involved the voices of characters, since the Graz singers had different accents,” says Lopez. Oberlin’s Collegium Musicum, directed by Professor of Musi-cology Steven Plank, recorded one sample, a Monteverdi madrigal, which appears in a pivotal scene. Half a dozen students from the College and the Conservatory helped run the very complex audio setup, including TIMARA major Katelyn Mueller ’07, who followed the score and called all 300 sound cues. Balancing the sound on all of these elements was a highly complicated process. “It was really gratifying to see the students take on these responsibilities and observe how the sound management got better and better with every performance,” Nielson says. And Lopez adds, “I’ll be using work we did in this opera for years to come.” Video of an Opera of a Film Responding to Neuwirth’s interest in visual elements, the Oberlin team created a whole new layer of video for the production that did not exist in Graz. The production had to be designed to work effectively in both Finney Chapel and in the Miller Theatre, and it had to be trucked from Ohio to New York and reassembled there. The visual aspects of the production were the province of Jonathon Field, Associate Professor of Opera Theater and Director of Opera Theater Productions, who took his cues from the composer’s notes in the orchestra score. “I tried to provide as many projection surfaces as possible to create a surround sense of video,” he says. Video is a central plot device in the film: Fred and his wife, Renee, receive unmarked videotapes that show the interior of their house, building Fred’s distress. The last videotape shows him standing over Renee’s bloodstained body, the only evidence of a murder he doesn’t remember committing.

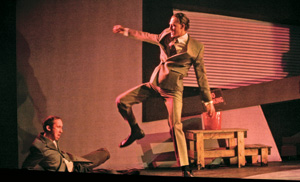

Given that the score itself has multiple layers, Field wanted to keep the stage action clear. “I looked at the shooting script of the movie and found that Olga had already interpreted a lot. So I kept it simple and plot driven.” And while Field has directed theater and opera, Lost Highway proved an unusual amalgam of the two. “Working with opera singers and actors together led me to this great discovery—that actors go from text to moment to timing, while opera singers go from timing to moment to text. They arrive at the same place, but their processes are completely inverted. I had to have faith that the opera singers would develop characters and the actors would deal with the timing requirements.” The students, perhaps by virtue of their age, seemed unfazed by the electronic aspects of the piece and coped with its other challenges as well. Field says, “I’m amazed to this day at how they pulled the pitches out of the air and kept with the rhythm.” In Character Michael Weyandt, who played the role of Pete, is a 2005 graduate of Oberlin in voice and composition, now studying for a master’s in voice at Indiana University. When he got wind of the project through friends in Oberlin’s Composition Depart-ment, he lobbied for the role of Pete, and took a semester off from IU to do it. Weyandt’s usual opera work runs to such baritone roles as Lescaut in Manon, so this one was very different. “It’s a miked show, and the composer did not want a traditional classical timbre—a rich sound—but rather a half-voiced, thinner sound, which was interesting.” he says. “Since I didn’t have to project lines in a traditional way, I could worry more about subtle colors, and that was exactly what she wanted.” He also had to speak English dialogue, which he hadn’t done since high school.

Alice Teyssier, who played the double role of Renee/ Alice, also has roots in contemporary music; a double major in flute and voice, she was a stalwart of the Contemporary Music Ensemble as a flutist and was in her fifth and final year during the production, working on a master’s thesis on the use of video in contemporary opera. [See The View From Here, page 38.] She made contact with Neuwirth during the summer of 2006 at a workshop in Europe where the composer was on the faculty. Her Lost Highway role was, she says, “a polar opposite” of others she’s done. “I’ve been the innocent type, the ingénue, so this was my first evil role.” Teyssier picked up on Neuwirth’s view of the two women, an interpretation that brings a dimension to the characters that was not portrayed in the film. “For Lynch, Alice and Renee represent the idolized, mysterious, ungraspable woman,” she says. “I see the two women as distinct characters, but they both seem to drive their respective partners mad. Renee is passive-aggressive and never answers to anything directly, while Alice leads Pete by the tip of his nose.” Cruising the New Music Road Both Neuwirth and Lost Highway screenplay author Barry Gifford spent time on campus, teaching classes and interacting with the producers and performers. Neuwirth’s principal concern was the sound environment, and the students and faculty were particularly impressed with her ears. “There’d be a section that sounded like cacophony, and she’d say to the percussionist, ‘I want a rubber mallet; you are using a hard mallet,’” Weyandt recalls. “She’s very detail-oriented. … I realized she had very specific reasons for everything.” Lewis Nielson notes that Neuwirth’s involvement made a real difference in the final project. “She can sing everything in her score, and she really knows what she wants, so you can really nuance a performance. The composer can take it up that one little notch and make it really explode. This was a high-risk project—and she wanted to go for everything. She had confidence in our ability to strive for it.” Sacks adds, “It was wonderful to work with her. Tim Weiss had a blast—seeing him channel her intentions and take her last-minute directions to the orchestra and run with them was really inspiring.” That’s exactly the sort of learning that David Stull was hoping to see. “We are interested in providing our students with extraordinary experiences,” he says. “A project like this has no model. As they grapple with it, and watch the faculty making choices and grappling with it, the education they glean is critical for a musician in the 21st century. How you access new music and new art, how you experience a fusion of disciplines, is something you need to know to be adept as an artist.”

Neuwirth’s thoughts about her art, beyond its purely technical considerations, made an impression on the students. “She very much wanted to talk about large-scale aesthetic issues,” Weyandt says. “She loves the operas of Mozart, and how he talks about humanity. All the crazy stuff she does, it’s for the purpose of expressing something about human nature, about the characters, ideas about relationships. Ultimately, she’s only interested in that side of the piece. Everything else is serving that. She believes in art.” For Nielson, the impact of the piece extends even beyond the learning process and Oberlin’s achievement in carrying out a project of such extreme complexity. “It tells our students that anyone connected with the contemporary arts needs to be on a mission to reestablish the importance of contemporary music in American society,” he says. “On campus, it was standing room only three nights in a row, and plenty of people saw all three performances. They left talking about it. If anything can get across the fact that contemporary music can be a communicative, vital, visceral experience, it is something like this.” |