BY MICHEL DEBOST

|

The sophistic question about chickens or eggs coming first translates to flute playing in terms of whether blowing or breathing comes

first or is more important. The answer, of course, is breathing, although it is blowing that creates a sound. Most flutists worry more

about taking air in than in managing its release.

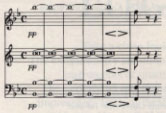

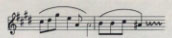

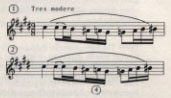

There are abundant examples of difficult passages in the flute repertoire for breath management: the first three movements of Bach's Partita, the first solo in Mozart's Concerto in D major K. 314, and the opening phrase of the "Cantilena" second movement of Poulenc's Sonata. In the orchestral repertoire are Ravel's Bolero and the beginning of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony. The latter was my personal nightmare, holding one single Bb for what seemed like hours without a second flute to help out, along with two clarinets and two bas- soons spanning three octaves. The more famous the conductor, the slower the tempo. This solo includes problems of pitch, breath management, and attack. Actually I prefer to play some of the technically difficult excerpts. Most auditions include Mendelssohn's Scherzo to Midsummer Night's Dream and Debussy's Prelude á l'Aprés-Midi d'un Faune. Although the Scherzo is technically demanding and requires great air control the Faune is a better example for breathing and blowing on long phrases. When playing l'Aprés-Midi d'un Faune in concert, breathing before the end of the first phrase doesn't matter, but in orchestral auditions flutists are expected to play the opening solo without interruption. Circular breathing, which is actually circular blowing, does not work here, so don't linger on the long notes and manage the air. Even when a player is in shape and able to perform the phrase in one breath, his main concern should be making music. By the end of the second bar, only the flutist knows whether he will make it through the phrase. After these opening 15 seconds, the listeners will have a pretty good idea about the flute player's music, breath or no. In order that the breath is not extended at the expense of tone quality, it is important to find a timbre and color that expends little air. Learn good air management concepts of tenuto, sostenuto, ritenuto, or in French, tenu, soutenu, retenu; to keep the rhyme in English, this would be "held, upheld, withheld," which is also often described by comments about breath support. However, support does not involve the diaphragm, which only can move one way, contracting for inhalations, while relaxing as the abdominal muscles contract for blowing or exhalation. In lifting a suitcase or leaning against a car with the upper body, the leg muscles contribute to the effort of the abdomen. When coughing or sneezing the intense energy of the muscles located just below the navel is aided by the actions of the thighs. For this reason I advise using the strength of the legs when standing for additional support. When seated the military posture of chin up, shoulders straight, elbows high, and buns on the edge of the chair is too stiff. Instead, try sitting with the lower back reclining against the lower potion of the chair, with the abdominal muscles pushed out while the feet are planted firmly for addition support. This is sostenuto. Instead of using weak facial muscles use the strong abdominal, leg and left arm muscles to help produce musical sounds. This is tenuto. The lips aid focus and tonal density, hut the left arm is the main agent. Flappy cheeks do not help to focus or control the tone in the extreme low or high ranges. The first joint of the left forefinger is the fulcrum for the flute and provides stability for technique, articulation, and sonority. Illustrations of players of transverse flutes through the ages show the flute resting halfway down the left forefinger. Even though the jaw and lip movements contribute to tone production, stability is essential. To physically feel the tenuto effect, try crossing the right hand over the left, which stays in place for this experiment: Loosely wrap the right hand around the trade-mark barrel between the lip plate and the first keys and play a simple low or high melody such as "Three Blind Mice" in G, using only the left hand. After the initial awkwardness passes notice how the focus is more controlled without spending too much air. Try playing the first bar of the Faune, repeating it three or four times in a loop until out of breath. For this, finger the A# with the left thumb, switching the key on and off as excellent training for using thumb Bb. Now consider how the Faune actually starts. The deliberately bland C# lacks a natural center because no fingers hold the flute. This note should have a beautiful reedy quality, bluegray, hollow, slightly fragile, and out of tune. After inhaling completely, start playing as soon as possible. Holding a huge quantity of air for any length of time means blocking the breath, which tends to make the attack explode. This poses no problem in an audition, but in concert, if the conductor is knowledgeable, he will signal the flutist to fire at will instead of following the usual downbeat, which could interfere with the inhaling process. Discuss such tactics with the conductor, but not during the rehearsal because it might appear as if you were teaching him his job or worse, that you have a breathing problem. Often played right after intermission, this piece cannot start a concert, end the first half, nor be last to finish a program (not noisy enough), so concentrating is difficult because the audience and orchestra are unsettled. When starting to play, remember to withhold (ritenuto) which means not blowing while maintaining rib cage expansion to resist its collapse. By sheer weight in the shoulders, some air will be expelled. Withholding maintains an open air cavity to counteract the support muscles in the lower body. Supporting but not withholding empties the chest quickly, so holding the phrase to its end is impossible. The secret is not blowing first until the end of the second measure, then releasing the chest air sparingly. After this blow push the abdomen; for the final notes, you can think crescendo, because air is running out. This support ultimately helps intonation. Finally, be on good terms with the first oboe and ask him to play his A# sooner than later without being too sharp because the flute tends to go flat at the end of the breath. Now, back to the inhaling process, which is more deliberate than the natural breathing function. First, as stress control and to oxygenate the blood, inhale three or four times deeply producing a "hhaah" sound which cools deep in the throat. As in exercising we run out of breath when the red blood cells need more oxygen to repair the muscles. Second, expel every ounce of air with an audible "sschss . . . tchhh" ending with collapsed chest, low shoulders, and concave abdomen. Third, start inhaling slowly through the nose, filling the chest cavity completely to the upper torso. Do this upper process first because the chest muscles work more slowly than the abdominals and taking air through the nose corresponds to upper breathing. Fourth, with an open mouth and throat and expanded belt area, inhale while producing the "hhaah" sound, then play right away. Do not use this lengthy process every time you breathe, only when preparing to play such a long phrase as Prelude a l'Apres-Midi d'un Faune. As an historical note, Dehussy'sPrelude á l'Aprés-Midi d'un Faune was premiered 99 years ago on December 23, 1894 and the flutist was Georges Barrère, then 18 years old. The record does not show whether he breathed in the first phrase, but the piece was so successful it was encored immediately. Michel Debost, former principal flutist of the Orchestre de Paris and professor of flute at the Paris Conservatory, currently teaches at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Oberlin, Ohio and presents master classes and recitals throughout the country and abroad. |