A Brilliant Speaker and a Passion for Art

A Brilliant Speaker

Tickets to a lecture by Adelia Johnston |

Adelia Johnston was well known outside her capacities as Dean of Ladies and Professor of History as a brilliant public speaker.

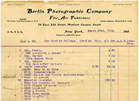

Whether calling for the abolition of slavery, or more often, exposing the Oberlin community to the history of European art, Johnston attained wide recognition for her oratorical skill. She put this skill to good use, selling tickets to her lectures and using the proceeds for various charitable causes, including the baseball team. Chief among her causes, however, was the accrual of photographic reproductions of works of art to be used at Oberlin. These early photographs, called heliotypes, were one of the few ways Johnston’s students could see the works of art when she lectured, so their value was paramount.

A Passion for Art

Mrs. Johnston brought the academic study of art to Oberlin at a time when art was used to dilute women’s education. She had already confronted the weight of popular opinion outside Oberlin (see The Struggle for a College Education). Now she persevered on campus, challenging her colleagues and fellow progressives to take art seriously.

The study of art as an academic discipline started in earnest in 1871, the year after Adelia Johnston was hired. In 1878 Professor Charles H. Churchill started giving the “Lectures on Architecture, Sculpture, Painting and Music.” Then Johnston’s colleague in the Classics department, Professor Charles B. Martin offered a course on the history of Greek sculpture in 1893. In 1895 he added Ancient art, such that by 1899 there were five art history courses offered.

Bringing Art History to Oberlin

Although drawing classes were taught at Oberlin as early as 1836, it was relegated to the Ladies Course, which led to a diploma, not a college degree. Women taking College courses were eager to study all that was denied them at other schools, rather than the “ornamental branches” of instruction; drawing and painting were considered skills, unlike the academic studies required for the College degree: Greek, Latin, higher mathematics and Hebrew.

Within one year of Adelia Johnston’s arrival (in 1871) the first credit course on the history of art, “Lectures on Art,” entered the curriculum. Studying art as an academic discipline was unusual in the 1870s. Although drawing and painting courses were offered across the country and objects illustrated history courses, the theoretical study of art was largely ignored.

As early as 1880, Johnston began to collect photographs during her many trips abroad to spur local interest in art among the college and community and to illustrate her lectures. Occasionally she interrupted her history courses to discuss the art of a period, to the delight of her students. She also used her bi-monthly lectures to the female students and eventually even the “Thursday Lecture” to discuss art.

|

|

Adelia Johnston taught with limited resources, but her oratorical skill and natural enthusiasm for the subject made up the difference. Her technique was described as “You were there.” She would reconstruct the culture surrounding a piece and describe the work with such power her students, and later the general public, fell in love with something they had never actually seen.

| Heliotype details, courtesy of the Oberlin College Visual Resources Collection. |

Johnston traveled abroad extensively and also hosted summer trips to Europe. It was on site that she taught herself, and later her students, to appreciate the art of Europe and Egypt. She sponsored academic field trips to Europe (1892, 1894, 1897, 1899) and a Winter Term in Egypt (1903).

Pink Haystacks?

Though largely self-taught, Adelia Johnston had a sophisticated understanding of art which is illustrated by her reaction to a radical new expression: Impressionism. The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 brought the work of the French Impressionists, notably Claude Monet, to the attention of the American public.

Impressionism’s radical approach was hotly debated at Oberlin as elsewhere. One dinner conversation in Baldwin Cottage is reported to have turned to this the “new school with its purple shadows and pink haystacks.” Mrs. Johnston’s perspective was simple and direct.

These artists were experts, they had trained themselves to see and they could and did see atmospheric effects which to ordinary people were not apparent. Moreover, these men were honest. If Monet painted a pink haystack it was because he had seen one.

Then turning to two young men who crossed the campus everyone morning on their way to breakfast she is reported to have said: “Now you watch, and when the morning the pink haystack comes, let us know.”

Months later in mid-winter the two students ran into Baldwin Cottage exclaiming: “Come to the Campus, come quick, the haystacks are pink this morning!” That morning Mrs. Johnston thanked God for the “beauties of nature” in the prayer over breakfast.

- The Woman Who Started It All

- Early Life

- The Struggle for a College Education

- A Brilliant Speaker and a Passion for Art

- Her Friends Became the Friends of Oberlin

- Later Life and Legacy