| << Front page | News | September 10, 2004 |

Architectural legacy of Oberlin

Buildings tell their own history and the history of the eras of Oberlin’s campus

|

||

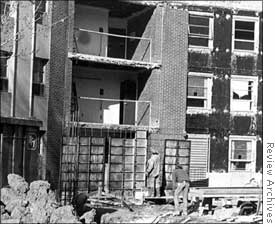

| Langston Hall: Under renovation, spring 1987. | ||

Back when the College was founded in 1833, there was no real town. The College was the touchstone around which to build a community and therefore affected the way both were built.

Oberlin’s original purpose was to turn out missionaries, ministers and pious school teachers and the town was a religious, communitarian experiment. Plain, even austere, life was valued and striven for. This was reflected in the architecture. Most domestic buildings were angular, wood-frame and gabled — very plain.

The town was also small: by 1890 the community population was at 4,300. As the College monopolized the industry market in the relatively homogenous town there was no, what historian Geoffrey Blodgett calls, “ ‘nouveau riche’ mercantile community.

“The town therefore lacked what architectural historians regard as a precondition for the showy, imaginative elegance which marked 19th century domestic architecture at its boldest,” he said.

In the 19th century, that was how Oberlin liked it. In fact, when fashion in architecture began to pick up in town, in the post-Civil War years before and after the Great Depression, Charles Finney spoke out against it. He said of these dissenters, “They exult in their good living. Proud of their luxuries…They mind their houses and grounds more than God…As bad as the cities.”

The College’s attitude towards building apparently has changed as of the 40 on-campus buildings. Only three date back to the 19th century and none before 1895.

This change in direction can be dated to when the college began to receive gifts from rich men. Among these contributors were Richard Peters, Elbert Baldwin, James Talcott, Lucien Warner, Louis Henry Severence, Andrew Carnegie and Herbert Wilder surnames that should seem strangely familiar.

Old buildings were junked without regret and continuously replaced with new ones up through the 1960’s. Post-WWII was an immense boom era. Of Oberlin’s 40 buildings, 24 were constructed in 1945. And for good reason: from 1940 to 1970, enrollment rose from 1,900 to 2,500. And there have been notable construction frenzies since (ie: the Science Center, the new Union Street housing).

One random and rather unusual building endeavor involves the ornamental bandstand, Tappan Square. It found its architect through a 1985 international competition initiated by college president S. Frederick Starr. The victor was ultimately a Canadian Oberlin alum named Julian Smith.

Perhaps the most significant architectural legacy began two decades earlier. From 1959 through the early 60s two of the school’s most important academic buildings were under construction: King and the Conservatory. They were both designed by Minoru Yamasaki, the acclaimed architect who also designed the World Trade Center.

This modernist turn has also inspired buildings like Langston dormitory, commonly known as North. Joseph Ferut, the architect currently working on the new housing project for the College, described the trend as “very typical of the 60s.” More importantly he spoke of the emphasis on “reducing ornament” and the concept of form following function. He spoke of this simplified style as not being aesthetically pleasing to everyone. Some find it completely uninteresting and some find it beautiful in its simplicity.

Maybe architecture has come full circle at Oberlin. Maybe even Charles Finney would approve.

About us

Subscriptions

Advertising

|