Nutritional Crusade

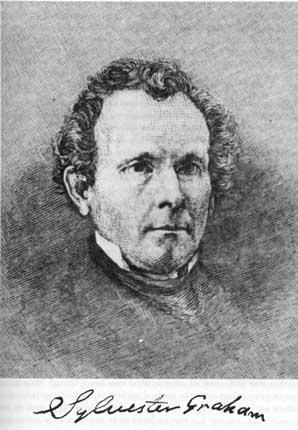

Sylvester Graham was a Presbyterian minister and reformer, best known for creating the Graham cracker. Regarded as a temperance minister, he promoted the benefits of moderation and believed that certain foods and behaviors are detrimental to both physical and spiritual health. However, he believed that it is not enough to practice moderation in all things, because some things are simply not good, for either spiritual or physical reasons, or both. These theories made him a central figure in the health reform movement of the 1800s. And some of his ideas made their way to Oberlin College in the late 1830s.

Sylvester Graham was a Presbyterian minister and reformer, best known for creating the Graham cracker. Regarded as a temperance minister, he promoted the benefits of moderation and believed that certain foods and behaviors are detrimental to both physical and spiritual health. However, he believed that it is not enough to practice moderation in all things, because some things are simply not good, for either spiritual or physical reasons, or both. These theories made him a central figure in the health reform movement of the 1800s. And some of his ideas made their way to Oberlin College in the late 1830s.

As part of his mission to promote healthy living, he became a vegetarian, which at the time was quite contrary to those whose diets included meat and other large meals. He stressed the use of whole-wheat flour rather than the refined flour used by urban bakers. In their process to refine, they stripped the flour of husks and dark oleaginous germ and whitened it with “chemical agents” because it baked more quickly than traditional bread, even though the result was an almost crustless loaf without granular texture or nutritional value.

The Graham bread he made, which we know now as Graham crackers, reached the market in 1829. It was high in fiber, and contained non-sifted whole-wheat flour that was coarsely ground and shaped into little squares. Graham also lectured widely on the benefits of healthy eating and living, and wrote materials on the subject, among them, Graham Journal of Heath and Longevity.

The College’s propensity to aspire to perfection and its history of temperance attracted a number of fads, including one that involved Graham’s invention of Graham flour and the Graham cracker. According to historians Robert Fletcher and Geoffrey Blodgett, Graham’s diet fascinated many, including leaders John Shipherd, Philo Stewart, Charles Finney, Asa Mahan, some Oberlinians, and College faculty. His diet prohibited the consumption of meat, as well as tea, coffee, wine, cider, rich pastries, and “all unwholesome and expensive food.” For a while, Oberlin’s dining halls served the Graham diet with water.

Not everyone was pleased. In opposition to meals consisting of Graham bread, plainly prepared vegetables, fruit, rice, and porridge, private boarding houses in town began serving hot meals with meat. Eventually College officials decided the Graham diet was “inadequate to the demands of the human system as at present developed” and returned to cuisine that included meat.

Graham continued his crusade and for a time served as an agent for the Pennsylvania Temperance Society. He died in 1851 at age 57. His work and those of others led to the gradual rise and acceptance of a vegetarian diet.

Sources: Oberlin College: A Historical Sketch by Geoffrey Blodgett; Oberlin Alumni Magazine, summer 1998; A History of Oberlin College by Robert Fletcher