The Tappans

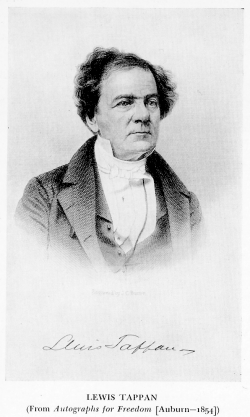

Massachusetts-born benefactors Arthur and Lewis Tappan put up the majority of the money needed to open and sustain Oberlin College. The Tappans, who acquired their wealth in dry goods, silk importing, and business investments; however, had a few stipulations that were initially met with opposition. One of them was an open admissions policy.

Massachusetts-born benefactors Arthur and Lewis Tappan put up the majority of the money needed to open and sustain Oberlin College. The Tappans, who acquired their wealth in dry goods, silk importing, and business investments; however, had a few stipulations that were initially met with opposition. One of them was an open admissions policy.

The Tappans, who were involved in the abolitionist movement and antislavery issues, wanted outspoken preacher Charles Finney to become professor of theology and former Lane Seminary instructor Asa Mahan to serve as the first president. They also wanted the faculty to have a significant role in managing the College.

The brothers wholeheartedly supported Oberlin founder John Shipherd and what he sought to accomplish in the burgeoning community. The donors agreed to provide the resources to the College under three conditions:

- the College hired specific faculty;

- faculty would control the admissions program and the entire internal management of the College; and

- the College would adopt a policy of open admissions irrespective of color.

The College admitted women in 1837 through the Ladies Department. Even then, College officials expressed concern about fraternization as well as what it should be teaching young women to prepare them for life after a college education.

Getting Oberlin’s Board of Trust to support these requests as well as the notion of inclusiveness did not come easy. Planners earlier polled the students enrolled at the time. Results showed 55 percent of the students were against black student enrollment. The issue was so controversial that board members held meetings to discuss this issue in nearby Elyria.

Although Oberlin was an antislavery community and its African American citizens lived and worked in the community as any other, the question of education hit a nerve.

Shipherd continued to write impassioned letters of appeal to benefactors and trustees, citing examples of other Ohio institutions such as Western Reserve College in Hudson and Lane Seminary in Cincinnati that had lost students, resources, and other support over antislavery policies and the issue of educating African Americans.

In the end, the trustees agreed to all of Shipherd’s and the Tappans’ demands. Failure to do so would have meant great loss for the promising College: loss of newly enrolled students from Lane Seminary, the loss of faculty leadership in Finney who was to develop a theological department, the loss of the Tappan brothers’ financial support, and the loss of academic freedom.

By fall 1835, Oberlin College ushered in its new open admissions policy, agreeing to admit students regardless of gender or color.

Information courtesy of A History of Oberlin College, volume 1 (1943) and Oberlin History (2006)