Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Fall 2008 Vol. 104 No. 1

Redefining an American Classic

Joining Brooks on stage is actress Petronia Paley, playing the role of Linda Loman.

Joining Brooks on stage is actress Petronia Paley, playing the role of Linda Loman.

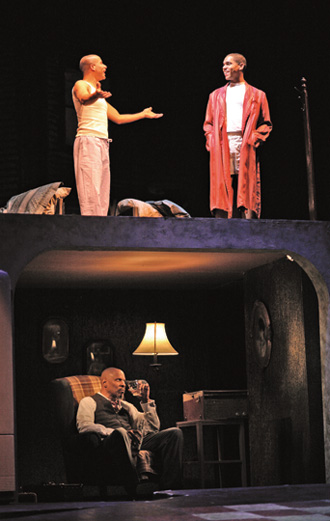

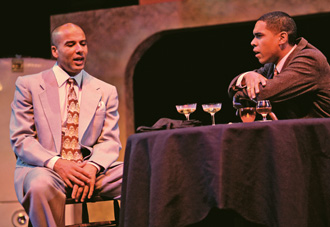

Justin Emeka ’94 as Biff Loman and Darryle Johnson ’07 as Happy Loman

Justin Emeka ’94 as Biff Loman and Darryle Johnson ’07 as Happy Loman

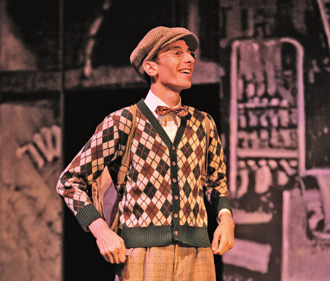

Josh Sobel ’09 as Bernard

Josh Sobel ’09 as Bernard

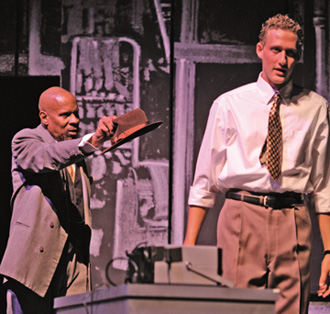

Raphael Sacks ’09 as Howard

Raphael Sacks ’09 as Howard

A mixed-race cast brings new light to Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman

For five weeks in August and September, cast members of the Oberlin production of Death of a Salesman wore out the path to their rehearsal space in South Hall. There was much to do in little time, and expectations were high.

In the mind of director Justin Emeka ’94—who has long thought about the need for nontraditional casting in traditionally white roles—the central characters in Death of a Salesman are not white, but African American. "In our production, Willy Loman is a charismatic, African American traveling salesman who lives with his family in a multiethnic Brooklyn neighborhood," Emeka says. "Next door to the Lomans lives Charley, a Jewish immigrant who fled Poland during the invasion of the Third Reich."

This wasn’t the first time African American actors had taken on nontraditional roles, of course, but the question for some was whether or not the playwright’s intended message had been changed by it. "Oberlin’s production explored how the construct of race—notions of whiteness and blackness—historically impact socioeconomic mobility, as well as identity and self-worth in America," said Emeka, a visiting professor of theater and African American studies, in an earlier interview.

"I’ve always believed very strongly in the importance of exposing the audience to a multicultural understanding [of a play]," he adds. "But I did have to remind myself that there would be people who just wouldn’t get it, or would even be offended, and that was okay. I really felt, and still feel, there is a huge audience waiting to see productions like this, productions that incorporate the diverse cultural perspectives of the American experience into American classical theatre. The question for me is not, ‘Why should we?’ but rather, ‘Why wouldn’t we?’"

It was the body of work by veteran stage and television actor Avery Brooks ’70 that first inspired Emeka to imagine a nontraditional approach to Death of a Salesman. Brooks, known by television viewers as Captain Benjamin Sisko on Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Hawk on Spenser: For Hire and A Man Called Hawk, had played lead roles in Shakespeare’s The Oedipus Trilogy and Othello and performed with Emeka in a production of King Lear. When tapped by Emeka for the role of Willy Loman at Oberlin, Brooks accepted, even agreeing to several weeks of summer rehearsals.

Among Brooks’ most notable Oberlin performances was his portrayal in 1997 of Paul Robeson, one of the first black men to play serious roles in white American theater. At the time, Brooks talked with OAM about cultural stereotypes he had encountered in Hollywood that were threatening to dilute his characters. Today, he says, we need a more elevated conversation about culture as it relates to acting and beyond.

"As we look at expression in this part of the world, we often deal with the superficial; it’s not art, it’s black art. It’s not music, it’s black music. We color it," says Brooks, who teaches theatre at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers. "That’s a part of who we are in society. This play is about the convergence of culture. Culture is everything—what you say, what you eat, how you speak, how you dress, and how you perceive economics and make decisions. When one views this play in that way, it becomes much richer."

To open the door for discussion of the play, Emeka and castmembers held a panel discussion titled "Arthur Miller’s Cross-Cultural Exchanges."

Days before Death of a Salesman took to the stage for ticket holders, Emeka invited high school students and teachers from nearby school districts to watch the performance and talk with the cast. Later, Emeka received a letter that nearly brought him to tears.

"I just wanted to tell you what an overwhelming experience this performance was for me and my students," wrote Teresa Jenkins, an English teacher at Lake Ridge Academy. "I had read that Miller’s original line for Willy was, ‘They laugh at me, Linda. They call me shrimp.’ When Avery Brooks said the line as, ‘they call me monkey,’ I audibly gasped. While the production made me realize how much higher the stakes were for this family, it reminded [me] also of how universal the stakes are for all of us.

"When I went home that night, I called my son, who is a Skidmore theater major in New York. We talked for over an hour about the production, and yes, about my pride in him. The Oberlin performance was nothing short of remarkable."

For much more, including photos, director’s notes, and blogs written by castmates, visit http://salesman.oberlinevents.org.

A Conversation with Justin Emeka and Avery Brooks

OAM: Why cast Avery Brooks as Willy Loman?

Emeka: Avery and I were introduced in 1996 by Oberlin’s late, great Calvin Hernton. From very early on, I imagined Avery as Willy Loman, heard his voice, saw his gestures, and imagined his sensibility in shaping the character. It wasn’t so much about his acting, but rather all of what he knew of the character. Avery is an extraordinary man, full of complexity and with a personality large enough to encompass all of what Arthur Miller had intended for Willy Loman, and all of what I had intended.

OAM: What was your biggest challenge?

Emeka: Besides directing and acting, it was balancing my vision of the play with Arthur Miller’s. It was important that neither vision overshadow the other, but that they constantly serve each other and work together as equals to reveal this extraordinary story. In my head, the story was always clear, but at some moments, I wondered if I was going too far, or not going far enough to provide clarity for the audience.

OAM: What new vantage point did an African American ensemble bring to this American classic?

Brooks: It’s about culture. And in this case, we were talking about American culture, of which African people are very much a part. So it’s not a stretch. It’s not odd. It’s not new. It is refreshing. Some people, of course, will say that we’re changing what Miller wrote. Well, we’re not changing what Miller wrote. When you talk about salesmen, you talk about black history. The fact that we have CEOs and heads of corporations is a result of the black people who pioneered sales and made the corporations include them and who included the black community among their markets. … How can [blacks playing nontraditional roles] be a new idea? This is not a new attempt to be clever or cute. This is a wonderful work. Great work is great work. It has no time, and it has no ownership.

OAM: As an actor, is it difficult to get people to understand your vision?

Brooks: I’m not trying to force anybody to do anything. I’m an actor because I’ve chosen to use what I’ve been given—my mind and most importantly my heart. I care about the world. [I’ve been given] a history, not just within my particular lineage, but a history of struggle, which is the sign of life. I’m doing this to be part of the equation of life saving and life giving. That’s what all of this is about.