Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Fall 2008 Vol. 104 No. 1

A World of Green

(photo by David Maxwell)

(photo by David Maxwell)

At Oberlin, "sustainability" is more than just a buzzword. On campus and in town, students, professors, residents, and businesses are setting and inspiring new benchmarks for environmental responsibility.

"Green, Greener, Greenest" read the headline of a New York Times story in July that described the attention-grabbing ways that college campuses across the country are racing to become the greenest of them all. Many are buying clean power and setting dates for achieving carbon neutrality; others are hiring campus sustainability coordinators, planting more trees, and swapping plastics for china in their dining halls.

Good steps? Yes. Effective? Maybe. As the Times points out, some campuses are taking easy steps to win the green label rather than doing the kind of unglamorous work—replacing heating systems, for example—that would actually reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide.

So what about Oberlin? The College continues its enviable reputation as one of the nation’s greenest campuses, but are its actions truly meaningful?

Yes, says President Marvin Krislov. "For many people in the College and town, sustainability and thinking about the future of our planet are critical—and probably the central calling of our time."

Within the realm of higher education, the words "Oberlin" and "environment" are nearly synonymous. The Sierra Club last year published a top-10 list of the "coolest" (most ecologically minded) schools; Oberlin topped the list. In August, Newsweek’s 2009 Kaplan College Guide issued a similar list, while Plenty magazine named Oberlin the college with the "greenest conscience." And just last month, Oberlin was one of 15 schools nationwide to achieve the highest grade of A- on the 2009 College Sustainability Report Card released by the Sustainable Endowments Institute.

Oberlin’s foray into the environmental limelight began in 1998 with construction of the $7 million Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies. Its use of green materials, eco-efficient building design, solar energy systems, and geothermal heating and cooling methods became a prototype for green buildings nationwide.

But the building had a parallel purpose—that of serving as a living laboratory for students. Professors in the Environmental Studies Program, notably David Orr and John Petersen, were eager to incorporate the Lewis Center’s technologies into their coursework and research. Quick to emerge from student-faculty teams were genuine, usable products and techniques—an energy monitoring system, for example—that have been adopted across the campus and beyond.

On an institutional level, however, Oberlin had its critics. The Lewis Center had set the bar high, and some campus environmentalists believed that the lessons embodied in it were not being fully embraced throughout the institution. Subsequent new buildings on campus—notably the Science Center and the Village Housing residential complex—did not have the fundraising dollars nor budgets to support the same degree of green. Moreover, other U.S. campuses—many actually inspired by the Lewis Center—were moving ahead with their own sustainability plans. Said one professor, "Oberlin needs to lead the way, not point the way."

Fortunately, Oberlin’s Board of Trustees was listening. In 2004, the board stated publicly that Oberlin must be a responsible steward of the environment and committed the College to a comprehensive environmental policy.

Oberlin affirmed its promise in November 2006, becoming the first of its peer schools to sign the American College and University Presidents Climate Commitment. The agreement pledges institutions to develop a carbon budget and a plan for achieving carbon neutrality. More than 570 colleges have since signed on.

Momentum on campus spread quickly. Oberlin hired its sustainability coordinator in 2007, boosted its green building and purchasing policies, and added a second solar array to the Lewis Center complex. A firm was hired to explore ways of moving the campus toward climate neutrality, perhaps by renovating the central heating plant and by upgrading buildings.

Equally important—and what sets Oberlin apart from other campuses—is a new alliance between the College and the city of Oberlin, one that aims to buy more green power; increase the energy efficiency of homes and businesses; and invest in green-collar jobs, green building developments, and locally produced energy sources.

"Oberlin, right now, has the opportunity to take the lead toward achieving a sustainable economy," says Oberlin City Council President David Sonner. "This new economy will arise from what President Krislov has dubbed ‘The Sustainability Alliance’—which is designed to benefit the business, industrial, and educational sectors of this community."

On campus, as the following package of stories illustrates, sustainability is more than just a buzzword. For students, actions go beyond the low-hanging fruit of shortening their showers, turning off lights, or recycling their soda cans.

Orb developers Alex Totoiu ’10, John Petersen ’88, and Adam Hull ’10 (photo by Kevin Reeves)

Orb developers Alex Totoiu ’10, John Petersen ’88, and Adam Hull ’10 (photo by Kevin Reeves)

The Color of Energy

It’s 3 a.m. in Talcott Hall. Lights are turned off, laptops are "sleeping," and shower stalls are dark and empty. In the lobby of Talcott, mounted to a wall near a bulletin board, a large glass orb glows with a soft yellow light. All is well.

Four hours earlier—when a party in the hall meant that TVs, lamps, stereos, and kitchenette microwaves were working in overdrive—that same glass orb, which had glowed yellow for much of the day, shifted suddenly to red. Why the change? Because the energy use in Talcott had hit a predetermined threshold—twice the normal level for 11 p.m on a Thursday.

The glowing orbs, which were mounted in the lobbies of six dorms last spring, glow green when a dorm’s energy use is half its normal rate, yellow when energy use is normal, and red when energy use doubles. They are the newest feature of Oberlin’s Campus Resource Monitoring System, which continuously measures and displays real-time electricity use in student housing.

"At a minimum, we hope the orbs will help people be more aware of their energy use," says energy orb developer Adam Hull ’10. "By making that connection, they’ll still occasionally remember that energy is a resource that we’re using all the time."

Hull, a 3-2 engineering major, was among a team of students who adapted the orbs from a commercial product first developed to display real-time stock market information. Associate Professor of Environmental Studies John Petersen and the students modified the orbs to include a wireless receiver that translates electricity consumption into colors within one minute of data collection. "Once you understand the display, it only takes a few seconds to see how your dorm is doing," says team member Alex Totoiu ’10.

These days, the practice of monitoring energy is inherent in Oberlin’s culture. For the past three years, a student-developed Campus Resource Monitoring web site has allowed students to track and compare their dorms’ consumption trends. The site also displays the environmental and economic costs of electricity in meaningful ways, such as the rate of greenhouse gas emitted, gallons of gas used, and dollars spent. An $812,000 grant received from the Great Lakes Protection Fund this fall will allow the College and several collaborators to expand and transform the system into a pilot program for Oberlin city residents and regional small businesses.

Petersen says the system—and the orbs in particular—are powerful tools for helping people reduce their energy use. "The fundamental goal of the feedback technology being developed here is to change people’s ways of thinking and acting," he says. "This is different from technologies such as solar panels and hybrid cars that allow people to reduce their environmental impact without changing their behaviors. Ultimately, we need both types of technological approaches to bring about needed change."

Kristin Braziunas ’08 (photo by Dale Preston ’83)

Kristin Braziunas ’08 (photo by Dale Preston ’83)

Let There be Light Bulbs

Q: What do you get when you combine 10,000 donated compact fluorescent light bulbs with a team of dedicated student leaders?

A: The Light Bulb Brigade

The generosity of an anonymous donor last spring allowed students to tackle the challenge of replacing 10,000 incandescent light bulbs with free, energy-saving compact fluorescents. The Light Bulb Brigade, which encouraged everyone on campus and in town to swap up to 20 bulbs each, built upon a campus effort in 2007 led by Andrew de Coriolis ’07 and Morgan Pitts ’07.

The 2008 coordinator, Kristin Braziunas ’08, worked with faculty advisor John Petersen to expand the brigade citywide. All in all, students collected three crates of incandescent bulbs—9,500 in total—now on display in the Lewis Center. An exchange of 10,000 bulbs, says Braziunas, equals a savings of about 6,500 tons of carbon dioxide over the life of the bulbs.

"It was very gratifying to see beyond my age group and realize that environmental issues are important to a lot of people," she says. "Building common bonds is one of the most important ways of pursuing an environmentally conscious future."

It Pays to be Green

Using energy more efficiently benefits not just the environment—but also one’s pocketbook. The upfront investment, however, can be substantial.

At Oberlin, students soon will be lending money to fund energy-efficiency projects on campus that demonstrate a tangible cost savings—replacing a leaky showerhead, for example. Money saved by the upgrades helps repay the loan.

Money for the loans is housed and invested in a new Green EDGE Fund (EDGE meaning Ecological Design and General Efficiency), created last year with startup money by the College and through a new $20-per-student optional green activity fee. The Edge Fund’s aim is to finance innovative projects that demonstrate environmental and economic benefits, while simultaneously educating and empowering students.

Senior economics major Lucas Brown helped spearhead the project last year, helped along by professors and administrators. "One of the most important outcomes was the development of a rubric for evaluating loan requests," he says. "Any student, professor, or staff member can propose a project for funding, but there must be a provable financial payback."

Nathan Engstrom, Oberlin’s sustainability coordinator, says he’s excited about a fund that "puts students in the driver’s seat. Most of our previous accomplishments have been products," he says. "This one is a process."

(photo by David Maxwell)

(photo by David Maxwell)

(photo by David Maxwell)

(photo by David Maxwell)

One Cool Campus: Oberlin’s Sustainability Portfolio

Sun Power: Where is the largest solar electric array in the state of Ohio? Oberlin College. The photovoltaic (PV) roof of the Lewis Center, when combined with the solar parking pavilion behind it, has a rated output of about 159 kW, which annually produces more electricity than the center consumes. The excess is sold back to the local power company.

Green from the Ground Up: Oberlin’s Green Building Policy ensures that all new construction and major renovations achieve a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating of silver or better. LEED is the nationally accepted benchmark for the design, construction, and operation of buildings that minimize energy use and maximize environmental benefits. The Phyllis Litoff Building will go a step further, aiming to become the first LEED gold music facility in the world. On a smaller green-design scale, Oberlin replaced the leaking, stone-paved roof of Harkness Hall with a vegetated roof last fall. The benefits? Lower cooling costs, better storm water retention, and a longer life span.

Clean Energy: A green-energy purchasing agreement with the city of Oberlin’s local utility company simultaneously reduces the College’s carbon dioxide emissions by about 20 percent and generates a "sustainable energy reserve fund" for city-wide projects. So far, funds have been used to study the feasibility of local wind power, help support the local alternative-fuels center, and provide startup funding for a locally based carbon offset program to make low-income homes in Oberlin more energy efficient.

Buying Power: A Green Purchasing Policy at Oberlin is in place to guide all buying decisions on campus, from encouraging the use of Energy Star-rated appliances and Green Seal certified floor cleaners to recycled copy paper and Green Label carpeting. Publications like OAM are printed locally at plants that are certified by the Forest Stewardship Council.

Putting Water to Work: Oberlin’s Living Machine, housed in the Lewis Center, treats and recycles wastewater via an ecologically engineered system that combines conventional wastewater technology with the purification processes found in wetlands. The system is designed to remove organic wastes, nutrients, and pathogens, so that water can be reused in the building’s toilets and landscaping. Also a research laboratory, the Living Machine is operated by students and is a focus of classroom learning.

Green Eats: Dining halls at Oberlin do more than feed students. Through progressive procurement policies, including a Farm-to-Fork program, sustainable seafood principles, socially aligned coffee choices, and cage-free eggs, Oberlin and the Bon Appétit Management Company offer nutritious meals that invest in nearby farms, dairies, ranches, and aquaculture operations. Nearly 40 percent of the food served in dining halls and co-ops is grown locally. And when mealtime is over, food scraps are composted and leftover cooking oil is recycled into alternative fuels.

(photo by David Maxwell)

(photo by David Maxwell)

Pedal Power: Oberlin is still incredibly bike-friendly. Most students and Oberlin residents own bikes. Those who don’t can inexpensively rent bikes by the semester from the Bike Co-op, a student-run bicycle repair, rental, and education center. In addition, the Student Union loans bikes at no cost to students, faculty, and visitors who want short-term access for exercise or transportation.

Sharing the Driver’s Seat: When four wheels are a must, students can turn to CityWheels, a car-sharing program that offers hourly or daily access to fuel-efficient vehicles. Oberlin became the first site in Ohio in 2006 to launch a car-sharing program, due largely to nudging by student members of Oberlin’s Environmental Policy Implementation Group. Open to students, academic departments, and town residents, the program reduces the need for privately owned vehicles.

What’s Mine is Yours: Need a desk lamp, a window fan, or even a new pair of jeans? Hit the "Big Swap," a free, end-of-semester item-exchange that puts unneeded clothing and dorm room supplies back into circulation. Anything left over is delivered to the campus "Free Store" or donated to local charities.

Party Responsibly: Oberlin’s four-day, 52-event Commencement/Reunion Weekend first went green in 2007. Meals featured locally grown foods served on plates made of "bioware." Hundreds of travelers purchased carbon emissions offsets, and graduating seniors signed a pledge promising to live their lives sustainably. In 2008, the weekend went carbon-neutral with a donation of carbon offsets by Bon Appétit. Events included a sustainability panel discussion, a composting demonstration, and several tree- and flower-planting projects. Travelers could rideshare their way into Oberlin, and hybrid vehicles were on hand for local transportation needs.

May the Best Dorm Win: Oberlin’s annual Dorm Energy Competition, in which students compete to lower their dorm’s energy use for two weeks, expanded last April to include a campus-wide Ecolympics. Events included the Light Bulb Brigade, an eco-volunteer day, and a contest to see which dorm’s trash cans had the lowest percentage of recyclable products.

Editor's Note - Effective April 22, 2010: Since this article originally appeared, the Litoff Building has been renamed. Oberlin's new home for jazz studies, music history, and music theory is now the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building.

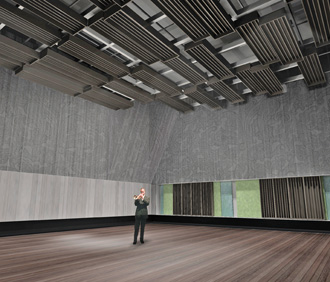

(Courtesy of Westlake, Reed, Leskosky)

(Courtesy of Westlake, Reed, Leskosky)

A Cool Home for Oberlin Jazz

(Courtesy of Westlake, Reed, Leskosky)

The Phyllis Litoff Building—Oberlin’s future home for jazz studies—is striving to reach an environmental milestone: becoming the first music facility in the world to achieve a LEED gold rating. Local and recycled materials, carpets and paints that do not produce off-gases, occupancy sensors that monitor ventilation demands, and a closed-loop geothermal heating and cooling system are being incorporated into the building’s design. The exterior, meanwhile, will be constructed of aluminum composite panels, ipé wood siding (ipé is a Brazilian hardwood that is harvested from naturally sustainable forests), and glazed curtain wall systems made of acoustically rated glass and fritted patterns to reduce solar heat gain.

Editor's Note - Effective April 22, 2010: Since this article originally appeared, the Litoff Building has been renamed. Oberlin's new home for jazz studies, music history, and music theory is now the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building.

SEED House resident Nora Sharp ’09 explains the hardware for the home’s resource monitoring system. (photo by David Maxwell)

SEED House resident Nora Sharp ’09 explains the hardware for the home’s resource monitoring system. (photo by David Maxwell)

Lucas Brown demonstrates the "Kill-a-Watt," an inexpensive device that measures the electricity use of appliances. "We use it to guess how much energy we use and to find the energy hogs in our house,"he says. (photo by David Maxwell)

Lucas Brown demonstrates the "Kill-a-Watt," an inexpensive device that measures the electricity use of appliances. "We use it to guess how much energy we use and to find the energy hogs in our house,"he says. (photo by David Maxwell)

SEEDs of Sustainable Living

(photo by David Maxwell)

Oberlin senior Amanda Medress comes home each day to a most unusual house. Outside, giant tanks are collecting rainwater, while inside, a bin of worms breaks down food scraps in the kitchen. Retrofitted with energy-conscious materials in 2007, this 130-year-old duplex on East Lorain Street serves as Oberlin’s first residential theme house devoted to sustainable living. The Student Experiment in Ecological Design, or SEED House, reflects its residents’ values, allowing them to make a difference just by how they live.

SEED House was brought into being two years ago by then-sophomores Lucas Brown, Kathleen Keating, and Medress, who put to work their academic lessons in environmental studies, economics, and politics. The students envisioned a carbon-neutral house with two goals: to serve as a community education center for sustainable retrofits and as a prototype for green student housing on campus.

Brown demonstrates how bathroom

sink water is reused to flush the toilet.

(photo by David Maxwell)

"What makes SEED House unique is that its theme is academically connected to the College," says Director of Residential Education Molly Tyson. "Students aren’t just living in the house; they’re connecting their living experience to academic pursuits."

SEED House residents—eight in all—have adopted a number of communal habits: keeping shower times to a minimum, limiting toilet flushes, and reusing "gray" sink water to flush toilets. The students opt for sweaters instead of cranking up the heat in the winter, and study together in a common room to avoid burning lights all over the house.

In 2007, after petitioning the College for renovation funds, the student founders moved the project to Professor David Orr’s ecological design class. There, students debated the best ways to refurbish and upgrade the 3,000-square-foot duplex, which was built in the 1870s with wood siding and no insulation. The class studied water and energy use, insulation, heating and cooling, and financing.

Taking student recommendations into consideration, the College helped with structural fixes and energy saving installations, such as water-saving faucets and ceiling fans. A resource monitoring system was installed that tracks and displays water and gas use and displays the electricity consumption in each student’s room. So far, the actions are working. Brown says the house uses just half the energy of a home with eight people, based on the national average.

Through incremental retrofits, the house eventually aims for carbon neutrality. "The models implemented in SEED House will help to inform future sustainability projects, not only in campus housing, but in academic spaces as well," says Associate Director of Facilities Keith Watkins.

But perhaps the most powerful outreach is the informal variety. "When friends visit SEED House, they see that we’re in a happy and healthy environment," says Medress. "Reducing our carbon footprint hasn’t meant deprivation. Rather, it’s been an enriching experience."

For a video link to SEED House, visit www.nytimes.com