Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Fall 2009 Vol. 105 No. 1

Around Tappan Square

(photo by Dale Preston)

(photo by Dale Preston)

Last year’s all-campus photo shoot in Wilder Bowl was so successful that the college decided to do it again. Office of Communications staffer Aries Indenbaum ’09 spent weeks working out details with Kevin Reeves, who reprised his role as Oberlin’s intrepid bucket-truck-riding photographer. After some maneuvering, and a lot of radio-to-radio communication, Reeves was able to position professors, staff members, and students into a tightly shaped O. For an overhead view of the photo, visit http://oberlin.edu/colrelat/allcampus/.

Half Dean, Half Scientist

Sean Decatur, Oberlin’s dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (photo by John Seyfried)

Sean Decatur, Oberlin’s dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (photo by John Seyfried)

Sean Decatur, Oberlin’s dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and professor of chemistry and biochemistry, is an interesting combination of scientist, professor, and administrator. This morning, wearing a snappy blue sports jacket and slacks, he greets me not in the dean’s office in Cox, but in his research laboratory in the Science Center.

As a biophysical chemist, Decatur for the past 15 years has researched proteins— "a class of really important molecules," he says. We both laugh at the understatement.

"What we’re interested in is trying to characterize the details of how proteins fold in the correct shape and what leads them to sometimes aggregate and fold into these incorrect, aggregated shapes," he says. The aggregates of misfolded proteins are the molecular root of serious ailments such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and cataracts in the eye.

Thus far Decatur’s research has lead to development of a technique to characterize the structural details of the proteins and their aggregates using infrared spectroscopy. The technique, he says, records the unique vibrations of functional groups in response to infrared radiation to help determine molecular structure. "By analyzing the vibrations very closely we can get details of how these aggregates are formed," and also what happens to interrupt this process.

In keeping with the liberal arts tradition, Decatur, as dean, is also interested in the culture of science, most importantly, the intersection of science and race. At his former post at Mount Holyoke, he initiated a race and science lecture series and offered interdisciplinary courses focusing on social and ethical considerations of emerging science. At Oberlin he is teaching a first-year seminar, Biotechnology: Science, Culture, and Ethics, to 14 students.

"We face a national challenge to increase the diversity of the scientific workforce," he says. "Not only do we need to include people of diverse backgrounds—especially groups underrepresented in the sciences, such as women, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans—but we also need to embrace interdisciplinary approaches to large scientific problems.

"The type of such education offered at Oberlin—rigorous, with an emphasis on hands-on research experience and creative, independent problem-solving—is a model for training the type of interdisciplinary scientists we need. We should emphasize making such education accessible to all."

Neuros in Europe

Pictured left to right: Seniors Jon Wachtel, Jasmina Makota, Adriana Akintobi, and Sam Krowchenko during a boat trip to Greenwich. (photo by Jasmine Makota)

Pictured left to right: Seniors Jon Wachtel, Jasmina Makota, Adriana Akintobi, and Sam Krowchenko during a boat trip to Greenwich. (photo by Jasmine Makota)

Eighteen Oberlin students, including nine neuroscience majors and one biology major, along with 15 students from Grinnell College, are part of this semester’s Danenberg Oberlin-in-London program. It’s the first time the study-away program has featured a member of Oberlin’s neuroscience faculty. Professor Jan Thornton is teaching two courses—Brain, Mind, and Madness and Emotions: Neural and Evolutionary Bases. "[We’re taking] some wonderful field trips," Thornton said via e-mail from London earlier this semester. "While in Oxford, we will visit the Museum of the History of Science and the Ashmolean, the first public museum in the world. It includes an 18th-century chemistry lab and scientific instruments. We will also visit [Sigmund] Freud’s house." In London, the group will tour the science museum, the natural history museum, and even art museums, where they will see artwork depicting mental illness, such as William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress. Students also planned to visit an exhibit called Exquisite Bodies, featuring old wax models used to teach anatomy to medical students in the 18th and 19th centuries. "Bizarre, but beautiful," says Thornton.

The Outdoor Classroom

The straw-bale garden shed built for Outdoor Classroom (photo by Jeff Hagan)

The straw-bale garden shed built for Outdoor Classroom (photo by Jeff Hagan)

When Shoshana Friedman ’05 visited Beth Blissman, director of the Bonner Center for Service and Learning, the seed for the local impact she sought had already been planted.

Actually, it was a whole garden.

Several years before Friedman showed up at the Bonner Center, second grade teacher Sarah Lee planted a community garden on the east side of her school, Oberlin’s Eastwood Elementary School, with her colleague Gail Burton. Lee’s hope was to turn the garden into a living learning place, to teach children about the cycles of nature—an outdoor classroom. But when maintaining the garden began taking too much time, the teachers had to abandon the project.

With that groundwork accomplished, Blissman asked Friedman to do some of her own harvesting: recruit more college students —including younger ones—to help bring the garden back. In return, the Oberlin students could receive private reading credit. Blissman hoped wrangling the underclass farmhands would make this sustainability project more sustainable.

Since then the program has "taken many forms," according to Zoe Dash ’09, who joined Outdoor Classroom in the spring of 2007. Now, 8 to10 Oberlin College students participate each year, helping with the garden-tending as well as teaching the lessons drawn from it. It has provided hands-on learning opportunities for both the elementary students and the college students.

"The program is wonderful," says Lee. "The [college] students have done a number of projects with our younger students —teaching them about the food chain, composting, healthy food—we even all built a straw-bale shed. We’re also learning about service to the community as a way to take care of the land."

Although Dash team-taught second grade, her favorite lesson last year was for kindergarteners. Titled "Meet Your Plant," each kid chose a plant in the Eastwood garden and was encouraged to learn everything they could about it through their senses—what it smelled like, how it felt, if it had flowers, leaves, a long stem, etc. Then they had to name it and introduce their new "plant friend" to the other students. "They were so excited that they now had their own friend in the garden!" says Dash.

The Class of 2013

(photo by Dale Preston)

(photo by Dale Preston)

- The College of Arts and Sciences welcomed 669 first-year students and 29 transfer students. The Oberlin Conservatory of Music enrolled 162 new students.

- 860 students represent 41 states and the District of Columbia, with the majority hailing from New York, California, Ohio, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Illinois.

- 4 students graduated from Oberlin High School.

- 107 students represent 35 countries—an especially large international class.

- 148 students identify as students of color.

- 55 percent of students are female, 45 percent are male.

- 56 students are the sons and daughters of Oberlin alumni.

- 27 students planned to enroll simultaneously in the college and the conservatory.

- On average, incoming students scored 700 on the critical reading portion of the SAT, 676 on the math section, and 690 on writing.

- 46 percent of the new conservatory class received the highest audition rating possible during the selection process.

- As a group, 79 percent of the new class (573 students) held leadership positions in more than 1,100 organizations.

Electricity Made from Scratch

David Lesser welds the turbine in the mechanic shop. (photo by Sarp Yavuz)

David Lesser welds the turbine in the mechanic shop. (photo by Sarp Yavuz)

It’s the start of fall break and senior David Lesser is nestled in the mechanic shop in the basement of the physics department. To the side of him are three hand-carved wooden blades. Resting on the floor are several used car parts—a front strut and a brake disk. After taking a moment to weld, Lesser pauses and says, "anyone can build a wind turbine.

"Nearly all of the stuff we’re doing isn’t technically difficult, potentially expensive, or fragile, and that makes this a good project for learning," says the physics major and founding member of Engineering People of Oberlin College (EPOC), a community of students interested in any aspect of engineering, including, but not limited to, design, mechanics, and electronics. Money for materials that EPOC couldn’t scrounge from local junkyards—about $800—came from the Oberlin Student Cooperative Association and the college’s Green EDGE Fund.

The turbine is just one of the projects the group is building; others on the discussion table include a bike shelter, electric car, and a steam scooter.

Although a home for the turbine has not yet been found, Lesser and the six other EPOC members who began constructing it last year say it could generate about 500 kilowatt-hours annually at peak performance.

"I’ve got a whole slew of other projects on the back burner," Lesser says of his personal pursuits. "I’ve already built an electric skateboard, and one of these days I’m going to get around to building an old-school vacuum tube amplifier." Lesser is also assisting Chris Martin, assistant professor of physics and astronomy, with construction of the Stratospheric Terahertz Observatory, a high-altitude balloon carrying a radio telescope that is expected to launch in winter of 2010-11.

Junot Díaz’s Dream

(photo by John Seyfried)

"I always drive my students crazy by saying, oh, that’s my favorite white writer," Junot Díaz told audience members in Finney Chapel in September, his voice dripping with sarcasm. The 2008 Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s convocation talk was just one of several events that was also part of Latino/Latina Heritage Month. "For me, the future would be that it’s OK for us to be not this universal writer, but it’s OK for us to be a Dominican writer, or a writer from New Jersey, and nobody [would] draw conclusions from that. That’s the dream."

Lovins: Energy Star

(photo by John Seyfried)

(photo by John Seyfried)

Thunderous applause greeted Amory Lovins, the college’s first convocation speaker of the academic year. Normally, star treatment is not bestowed upon a physicist, but Lovins, head of the Rocky Mountain Institute, where he helps businesses and governments understand that using natural resources efficiently is both profitable and better for the environment, was dubbed by Newsweek "one of the Western world’s most influential energy thinkers." On a carbon-conscious campus like Oberlin, he’s a celebrity.

"The kinds of organic and sound forestry practices we see increasingly adopted— often for other reasons—can actually make better farmland and rangeland and forestland into major carbon sinks that can soak up a lot of carbon out of the air more profitably then our current techniques that treat soil like dirt," Lovins said during his talk, "Profitable Solutions to Climate, Oil, and Proliferation."

Lovins was equally interested in individual scale solutions, such as Property Accessed Clean Energy (PACE) bonds. Pace bonds are a new innovation that could enable anyone to fix up a building without needing their own money, he explained. "[This bond] could end up retrofitting every building in the country."

Keeping the Peace

(photo by John Seyfried)

"Women across the world still face discrimination," human rights activist and 2003 Nobel Peace Prize recipient Shirin Ebadi told an Oberlin audience in October. In 1975, she was the first Iranian woman to preside over a legislative court, but was demoted to a clerk following Iran’s Islamic Revolution. For the next two decades, Ebadi devoted her life to the promotion of women’s rights, the defense of children, and political activism, at times despite great risk to her own safety. Her organization, the Association for Human Rights Advocates, provides pro bono legal service to political prisoners in Iran. "In European countries, as well as in the United States, women enjoy equal rights by law," Ebadi stated through an interpreter. "But because of their roles in society and at home, they have few opportunities to enjoy those rights."

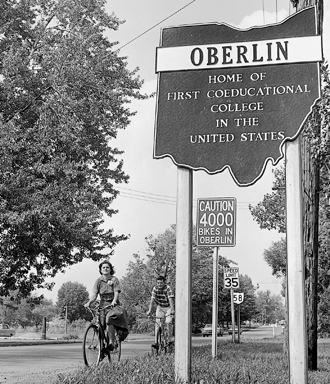

4,000 More Bikes in Oberlin

The historic—and inspirational—bike sign

The historic—and inspirational—bike sign

In an effort to encourage Oberlin students and permanent residents alike to become more environmentally conscious, college senior Dory Trimble is asking community members to sign a pledge that they will, whenever possible, ditch their cars in favor of a bicycle. Since September the group has registered more than 250 bikes.

Backed by a grant from the Oberlin EnviroAlums’ Student Sustainability Fund, Trimble’s project aims to "transform Oberlin into a community that’s happier, healthier, safer for cyclists and pedestrians, and better for the environment." The name of the project, 4,000 More Bikes in Oberlin, is a nod to Oberlin’s history as a bicycle-friendly town and recalls a semi-famous photo taken in the 1960s that proclaimed Oberlin home to 4,000 bikes.

Cyclists are asked to take a pledge that commits them to bike more and drive less and to "engage friends and neighbors in conversations about their decision and why they are making it, and get involved with community events."

Those registered receive such perks as a discount at the local bike shop and entry in an ongoing series of raffles for helmets, locks, safety lights, and other gear.

Read more at http://4000more.org/.

$1.7 Million Gift Funds

Conservatory Scholarship

Throughout her long life, Helen Hodam gave generously of her time and talents, helping dozens of students to build careers in classical singing. Now, another generous gift will continue her life’s work, allowing generations of talented young singers to study at the Conservatory of Music.

A $1.7 million gift from the legendary voice teacher’s estate has been established and will endow the Helen Hodam Merit Scholarship in Voice. A professor of singing at Oberlin for more than two decades, "Miss Hodam" was one of the most distinguished voice teachers in the United States. She died on May 21, 2008, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at the age of 93.

In celebration of her life and legacy, opera singer and former Hodam student Denyce Graves ’85 presented a recital in Oberlin in October.

The scholarship fund will enable extraordinary undergraduate students to attend the conservatory. The Class of 2014 will likely include the first students to benefit from Hodam’s scholarship gift.

Wave Makers

Courtesy of the theater department

Courtesy of the theater department

Kwame Webster ’10

Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana

Campus/Community Involvement:

Admissions office assistant and member of ABUSUA; Agape Christian Fellowship; Pseukay, Oberlin African-American performance company; and the Brotherhood, an organization that seeks to provide support for male students of color.

Kwame Webster is an African American studies major with a unique way of immersing himself in Africana history—through theater. Webster, who has been acting since the third grade, has taken part in a slew of performances at Oberlin dealing with issues of race and the black experience, including Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, In the Blood, Sankofa Theater, and, most notably, Death of a Salesman, starring Avery Brooks ’70 as Willy Loman.

"The most important views into any cultural experience are the ones that cannot be found in newspapers or sometimes history books," Webster says. "[Stories of] the quick-witted musicians who shared an interesting bond, the lesbian Blues singer, the father who kills himself trying to make a living for his family—all are part of the black experience. In Ma Rainey, written by black playwright August Wilson, an Afro-centric stance is present throughout. In Death of a Salesman, one simply has to put each scene into context to gain a particular view of black culture.

"So much of our history has been chopped up and messed around," he adds. "It’s a good feeling to be able to piece that back together and have a better connection to it through acting."

Webster plans to attend medical school after graduation, but hopes the stage won’t be far behind. "Theater keeps my sanity, and I don’t think I can ever stop doing it," he says. "I may not be on a main stage with a large part, but expressing oneself through the role of another character is a liberating and thought-provoking process."

Talking Points

- The National Science Foundation awarded Oberlin two grants totaling more than $1 million dollars for innovative interdisciplinary projects in the sciences. One grant will support the integration of computational modeling into science curricula, the other will be used to purchase a powerful new research instrument.

- Oberlin was awarded the highest grade given to any college or university, an A-, on the Sustainable Endowments Institute’s College Sustain-ability Report Card 2010. This is the second consecutive year Oberlin has earned top honors.

- Edward F. Hartfield ’72 was nominated by President Barack Obama to serve on the Federal Service Impasses Panel of the Federal Labor Relations Authority. Hartfield is executive director of the National Center for Dispute Settlement.

- Grover Zinn, emeritus Danforth Professor of Religion, and David Young, emeritus Longman Professor of English, were awarded emeritus fellowships from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Zinn is studying the writings of Hugh of St. Victor. Young’s fellowship will support his translation of three books by the German poet Paul Celan.

- Oberlin was awarded the 2009 Alfred P. Sloan Award in Faculty Career Flexibility. The award provides Oberlin with a $200,000 accelerator grant to expand career options for faculty and incorporate discussion of career flexibility into its junior mentoring program.

- Oberlin installed a 175 kilowatt-hour solar panel on the north end of Savage Stadium. The electricity generated is expected to power the football, baseball, and softball scoreboards, along with a surplus to feed back to the electrical grid.

- President Marvin Krislov was among 57 liberal arts college presidents to sign an open letter endorsing the Federal Research Access Act of 2009.

- Diane Meier ’73, 2008 MacArthur "genius grant" winner, gave a public lecture at Oberlin in September titled "Palliative Care: Transforming the Experience of a Serious Illness." Meier is one of the nation’s leading experts on geriatric care.

- Professor of Organ James David Christie provided musical accompaniment during Senator Edward Kennedy’s funeral in September.

For more information, visit: www.oberlin.edu.