Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Fall 2013 Vol. 108 No. 4

"Oberlin Vouches For Them..."

Forced into internment camps and barred from attending West Coast colleges and universities

during World War II, Japanese American

students found a new home at Oberlin.

By Lisa Chiu

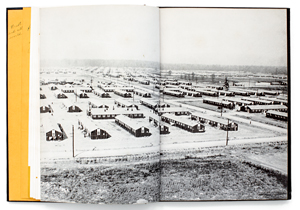

A number of Oberlin students of Japanese ancestry were interned

at the Heart Mountain detention center in Wyoming, including Soichi

Fukui ‘44; Roy Nakata and June Kimora (who both graduated from

San Jose State College); and Mai Haru Kitazawa Arbegast ’45.

The day after the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, the California high school that Alice Imamoto Takemoto ’47 attended held an assembly. The school principal specifically addressed Takemoto and her fellow Japanese American students.

“He said we were not the enemy,” Takemoto says. “That set the tone.”

A studio photograph of Alice Takemoto ’47 during her Oberlin years.

While she felt relieved by the principal’s words, outside of school she did not always feel as welcome.

“We didn’t go to the movies often—only very, very rarely,” the 86-year-old California native recalls. “When we did, the newsreels always had all of this propaganda about Japanese people. They put such fear into people that we were the enemy. The hostility was all around.”

In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed Order 9066, which authorized the secretary of war to designate certain areas military zones and eventually allowed the U.S. government to relocate more than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry—some two-thirds of whom were American citizens—from the West Coast and southern Arizona to assembly centers and then longer-term camps inland. Takemoto and her family were among them. They were sent first to live in a racetrack stable in Santa Anita, California, before being moved to a camp. After the initial roundup, the government began allowing Japanese American students to enroll at non-West Coast educational institutions that would sponsor them. That’s when Takemoto first learned of a school that might accept her.

“I was in a relocation camp in Arkansas,” she says. “People were starting to leave the camp to go to college. Word got around that Oberlin College had a student body president who was a Nisei [person born in America of Japanese-immigrant parents]. I just figured that was a friendly place. And that was the sole basis for my decision to go there.”

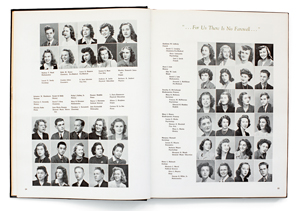

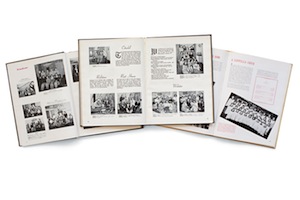

The 1943 Denson High School yearbook from the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas. “Cameras were contraband,” says Alice Takemoto ‘47, “so while I was in camp, the only pictures were in our high school yearbook.”

Oberlin became that friendly place very early on, answering the call when West Coast college and university presidents contacted peers at Eastern and Midwestern institutions asking them to accept Japanese American students who were being forced to leave their campuses. In 1942, Oberlin accepted 17 Nisei students. When one of them, Kenji Okuda ’45, was elected student body president within a month of his arrival, it made national news. According to research conducted by Clyde Owan ’79 and Cassandra Guevara ’13, close to 40 Nisei students made their way to Oberlin during the wartime years.

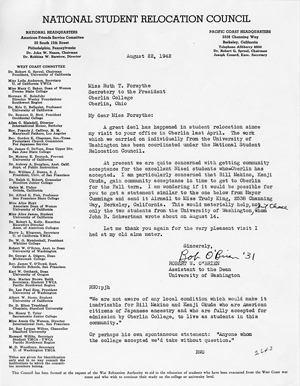

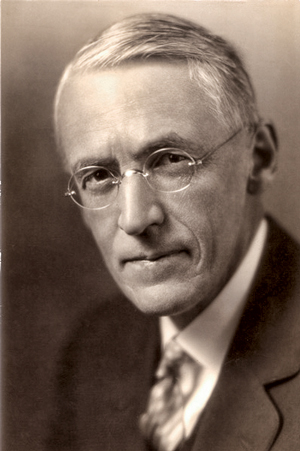

Oberlin president Ernest H. Wilkins sought to recruit Japanese American students even before the U.S. government-approved National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) was formed in late May 1942. Wilkins asked Harry Yamaguchi ’43, a sophomore at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, to recommend other deserving Nisei. He also worked with officials at the University of Washington—which had a high number of American students of Japanese ancestry, corresponding often with its president, Lee Paul Siegand, and Robert O’Brien, an assistant to the dean of arts and sciences. O’Brien had earned a master’s degree at Oberlin in 1931 and had served on the Oberlin faculty before moving west. He was named chair of the Student Relocation Committee of the Northwest College Personnel Association in April 1942, which was formed to coordinate resettlement plans for students forced to leave the Pacific Northwest. O’Brien advocated on behalf of the students and navigated the labyrinth of administrative government and university paperwork required to coordinate Nisei student transfers.

Letter from Robert O’Brien to Oberlin College suggesting ways the mayor of Oberlin could express the community’s support of the Japanese American students’ presence in Oberlin.

In a June 1942 letter from O’Brien to Wilkins, he writes, “I want to take this opportunity to again thank you for the leadership you have taken in perpetuating the Oberlin traditions that mean so much to her alumni.”

Kenji Okuda was a student at the University of Washington when the war broke out. His family was uprooted from Seattle and eventually sent to an internment camp in Granada, Colorado. Okuda, who passed away in 2011, shared his recollection of the tumultuous time in a 2009 video interview hosted by radio and cable television host David Ingram:

“A friend of mine called me from Oberlin—he was a student—saying his president had received the message from the president of the University of Washington,” Okuda said in the interview. “[President Wilkins] had called him in and asked if he had any friends that he would recommend to become students.”

Okuda told his Oberlin friend that he was interested in attending Oberlin.“Oberlin asked me to send whatever credentials I could. And within a week or two, they had accepted me.”

An October 1, 1942, editorial in the Oberlin News-Tribune explained the college’s perspective on the decision to admit transferred Nisei students:

“True to its best traditions, the Oberlin community bids these Japanese Americans a completely friendly welcome. They were born in the United States—in California, Oregon, Washington, New Jersey, and Hawaii. They all have excellent records of scholarship, character, and citizenship. They have been excellently recommended by friends of Oberlin, and Oberlin College vouches for them.”

The 1946 Oberlin College yearbook, Hi-O-Hi.

Not every school was as accommodating nor every town as hospitable. In late May 1942, at the request of the federal War Relocation Authority, the American Friends Service Committee founded the NJASRC to coordinate the resettlement of students nationwide. The organization sent questionnaires to college administrators to gauge their willingness to take in the students. Many schools never returned the surveys or refused. Even colleges receptive to the students worried about the reaction from their surrounding communities, which sometimes included protests from groups like the American Legion. A Pennsylvania legislator sought to cut off state funds going to colleges accepting the students. The governor of Idaho decreed no out-of-state Nisei would be permitted to enroll in his state’s institutions of higher learning. The mayor and city council of Parkville, Missouri, vigorously opposed the prospective arrival of seven Japanese American students.

“We do not believe there are any Oberlin citizens who are so lacking in common humanity, or whose patriotism is of such an empty, bombastic variety as would allow them to adopt the attitude of Parkville’s mayor,” the News-Tribune editorial stated. “If so, they surely do not deserve the name of Oberlin, and we wish them elsewhere.”

After developing allergies in campus housing, Alice Takemoto moved in with the family of Kenny Worcester, whose family owned the local dairy. They are pictured here in 1946 (left). Takemoto visiting her parents at the Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas after her first year at Oberlin (right).

Clyde Owan, a third-generation (Sansei) Japanese American, became interested in Oberlin’s role in welcoming Nisei students when by chance he learned that family friend Alice Takemoto was also an Oberlin graduate. He was playing golf with her husband, Kenneth, when he discovered their shared Oberlin connection. “That’s why you should always wear an Oberlin shirt,” Owan says.

Owan teamed with Oberlin archivist Kenneth Grossi and then-senior Cassandra Guevara to research the era and connect with other World War II Nisei alumni. Starting with a list of 17 students, Guevara spent the last semester of her senior year on the project and documented the enrollment of 39 Nisei students at Oberlin during the wartime years.

Besides conducting online research, Guevara worked with Grossi to find Oberlin yearbooks, letters, admissions essays—some handwritten, some typed—and other materials from the era. She maintains a blog to share the stories of their individual paths to Oberlin. Among the documents posted is a 1942 admissions essay by Dave Masato Okada ’44 in which he describes his immigrant family life in California.

At age 17, Okada lost both parents and had to work full time to support his four younger brothers. His interests in high school and junior college included baseball, Spanish honor society, music, and drama club. Okada’s admissions essay, written from an internment camp, reflected the turmoil caused by the forced relocation:

Today, as a consequence of the war, I have entered a new phase of my life confined (physically) for the moment within the bounds of an internment camp. The future at best is uncertain and I do not know what great changes, both social and economic, will come about as the aftermath of this war to affect the lives of us American citizens of Japanese extraction.

Life During Wartime

February 19, 1942

Executive Order 9066 signed, authorizing the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast

March 18, 1942

War Relocation Authority created by U.S. government

May 29, 1942

National Japanese American Student Relocation Council formed under the leadership of the American Friends Service Committee, with support from national organizations like the YMCA and YWCA

December 17, 1944

Public Proclamation No. 21 issued declaring that effective January 2, 1945, Japanese Americans could return to their homes

Takemoto with her father at 47 Vine Street in Oberlin on the day she graduated.

December 18, 1944

Supreme Court upholds detentions

August 1945

Japan surrenders

February 19, 1976

President Gerald Ford signs proclamation entitled “An American Promise” rescinding Executive Order 9066

June 1983

Presidential commission issues report concluding that the exclusion, expulsion, and incarceration of Japanese Americans was not justified by “military necessity” and that the decision was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The commission recommends that Congress pass legislation that recognizes “grave injustice” done and offers the nation’s apologies and compensation to each of the estimated 60,000 surviving persons

August 10, 1989

President Ronald Reagan signs Civil Liberties Act of 1988, requiring payment of reparations and apology to estimated 60,000 survivors of internment

October 9, 1990

First letters of apology signed by President George Bush presented to oldest survivors of Executive Order 9066 at Department of Justice ceremony along with redress payment

Alice Takemoto came by train to Oberlin accompanied by her older sister, Grace Imamoto Noda. Noda had been only three credits away from graduating from the University of California, Berkeley, when she was forced to leave. She took a job as an assistant cook to support her younger sister. Takemoto had been awarded a full piano scholarship, but Noda paid for her board and enrolled in Oberlin for a single class. She was finally awarded her Berkeley degree in 1945, after West Coast restrictions had been lifted.

Oberlin’s eighth president, Ernest Hatch Wilkins, who moved to help interned Japanese American students settle at Oberlin.

Eugene Shigemi Uyeki ’48 transferred to Oberlin from the University of Utah. His admissions essay to Oberlin described the deep disruption of the evacuation experience:

The days went merrily along. Heedless of the gathering storm clouds, most of us were busily engrossed in our play. Then the storm broke with all its fury, and our nation was plunged into the world holocaust. From that day since, like millions of other Americans, my life has not been the same.

Born and raised in New Jersey, Yoshie Takagi Ohata ’46 had planned to attend an East Coast university but reconsidered after learning that West Coast Nisei students were being evacuated. Takagi’s essay, “I’m Glad I’m an Oberlin Graduate,” is posted on Guevara’s blog:

If it weren’t for the war years, I most likely would have attended another college. However, I’m glad I’m an Oberlin graduate, as it provided me with a well-rounded background and a social consciousness that has been an asset as a wife, mother, and physician.

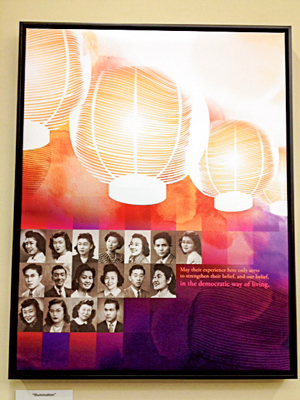

Illumination

Illumination, a new piece of artwork that graces the Dewy Ward ’34 Alumni Center, pays tribute to the Nisei (second-generation Japanese American) students who attended Oberlin at a time when Japanese Americans were banned from attending many colleges and universities.

Designed by Kartika Huston Redding ‘00 and commissioned by Clyde Owan ’79, it features 17 Oberlin yearbook student photos, referencing the Nisei students mentioned in an October 1942 editorial in the Oberlin News-Tribune. The student photos are presented beneath a string of large glowing Japanese lanterns, connecting them both to their Japanese ancestry and Oberlin’s Illumination Night commencement tradition.

Despite the black-and-white photography and their period clothes, what struck Redding was “how similar they look to students today—bright, hopeful, confident, and ready for life’s next adventure. The photos made me reflect on the individual journeys, the difficulties, and the extreme challenges they each had traveled before they arrived at Oberlin.”

Owan, a third-generation Japanese American (Sansei), agrees. “If you take the time to look at the faces of the students and think about all they went through, it just gives you pause,” he says. “I was very moved by their courage because they had encountered such hatred and ignorance, with very few people standing up to assist them.”

Redding included the Illumination tradition because she feels it’s “a powerful symbol for the light that Oberlin shares in its traditions of progressive thought, social and cultural activism, and leadership in the academic community.”

– Lisa Chiu

Like all new students, the Nisei students’ experiences at Oberlin varied. Takemoto was only 16 when she arrived, which already made her feel socially awkward. Her Japanese heritage added to her feeling of isolation. “I was very young, I was very small, I was very shy, I was very afraid, too,” she says. “It was wartime, and I didn’t know how people felt about me.

Kenji Okuda flourished at Oberlin. Although he was accepted in August 1942, administrative hurdles delayed his admission. Finally, the FBI cleared him to transfer from the University of Washington.

“In January or February of ’43, I finally got to Oberlin,” Okuda said in a 2009. “And then a month after I got there, I was elected president of the student body.”

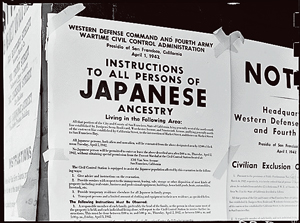

Relocation notices posted on the West Coast.

Okuda’s election garnered local and national media attention, including Time magazine coverage, which stated, “A typical evacuated Nisei student is Oberlin College’s lanky, 20-year-old, bespectacled Kenji Okuda. … Hustled into a Colorado relocation project (his parents are still there) after Pearl Harbor, he was released early this year. At Oberlin, Kenji heeled the college paper, made a hit, became student council president.”

Okuda wrote to a friend with the news. “I am now Student Council President of Oberlin College!” he exclaimed. “Greet me with the proper amount of dignity—with the dignity that the prexy of the Associated Students of Oberlin College will receive. I understand the AP & UP were down here to get more news, & so I may have become an ‘international figure’ as the dean of men jokingly told me. The news was also broadcast over a newscast & mentioned in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. What a life!!! Only a month & a half here, a part scholarship out of the clear blue sky, & now the Student Council!”

Jean Mieko Morisuye Conklin ’48 felt safe and comfortable at Oberlin. She shared her thoughts, which Guevara posts on her blog:

To my knowledge, the Nisei students were treated very well on campus and in town. It is possible that I was given a single room, albeit a very tiny one, my freshman year because they were not sure of a roommate’s reaction. But my room became a gathering point, and I made many lifelong friends that year.

The Hi-O-Hi yearbooks from (from left) 1944, ‘45, and ‘43.

Growing up Japanese American during World War II left a lasting impact on the Nisei students at the college. After they left Oberlin, they pursued careers and interests in advocacy, law, medicine, music performance, philanthropy, and sociology, among other fields.

Their internment and Oberlin experiences profoundly influenced their career decisions and life paths. A shy and awkward teenager when she arrived at Oberlin, Takemoto today is happy and productive, practicing violin at least an hour a day and performing in string quartets. She also partners with her son Paul to educate younger generations about the Nisei experiences as a way to prevent the mistreatment of other minority groups during times of uncertainty and fear, noting that no act of sabotage or subversion was ever linked to the Japanese Americans during WWII. Her years as a Japanese American student during the war helped shape who she is today. “Having had that experience as a young person” she says, “I guess it’s given me the confidence to do what is put in front of you.”

Lisa Chiu is a writer and editor in Cleveland. Cassandra Guevara ‘13 provided additional research.

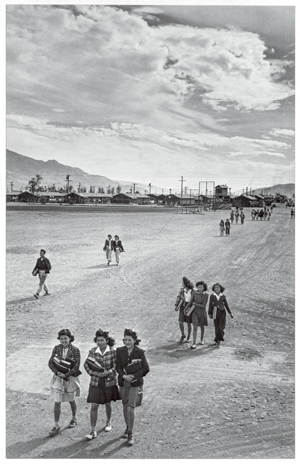

School children at Manzanar relocation center, California, 1943.

Photograph by Ansel Adams.

Japanese American students attending Oberlin during World War II (1939 – 1945)

Female: (spouse surnames listed in parentheses)

Mineko “Minnie” Sasahara (Avery)

Teruko Akagi (Brooks)

May Kitazawa (Arbegast)

June Kitazawa (Barr)

Jean Mieko Morisuye (Conklin),

Lily Yuriko Fukuhara

Michiko Matsushima (Fujimoto)

Yuriko Ito

Myra Iwagami

June Kimura

Shizuko Koda (Kitaoka)

Margaret Yokota (Matsunaga)

Ichiko Mukai (Hisanaga) ‘43

Alice Imamoto (Takemoto) ‘47

Grace Imamoto (Noda)

Yoshie Takagi (Ohata) ’46

Esther Matsu Kinoshita (Ujifusa)

Itsue “Sue” Hisanaga (Yamaguchi)

Mitsuko Matsuno (Yanagawa)

Ruth Sachie Kono (Machara)

Yoshie Morinaga

Midori Satoni Odo

Male:

Ray Masaki Egashira

Renso Y. Enkoji

Victor Tadaharu Fujiu

Soichi Fukui [sansei]

Arthur Shuntetsu Kodama

William “Bill” Makino

Calvin Ninomiya

Sammy Junsuke Oi

Dave Masato Okada

Kenji Okuda

Sadayoshi Omoto

Paul Kasumi Ushijima

Eugene S. Uyeki

Harry Goichi Yamaguchi ‘43

John Minori Nishiyama

Roy Nakata

Hisayo Morinaga

Willard Glenn Sueoka [may be a sansei?]

If you know of other Japanese American students who attended Oberlin during the World War II years, please contact the college archive office at (440) 775-8014.

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.