Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Fall 2013 Vol. 108 No. 4

Kid Lit Comes of Age

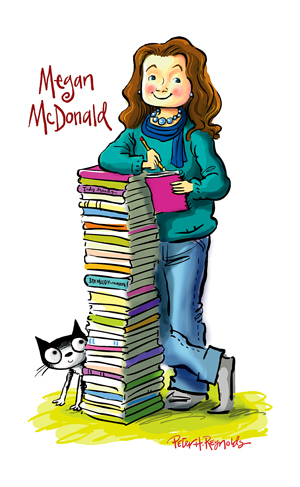

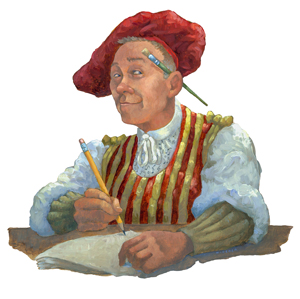

Megan McDonald ’81

Illustrated by Peter Reynolds

The Oberlin Alumni Magazine asked several of our authors’ book illustrators to create portraits of the writers with whom they’ve worked. For Judy Moody author McDonald, Reynolds was sure to include Mouse, Moody’s pet cat.

Harry Potter. Madeline.

Wilbur. Encyclopedia Brown (created by the late

Donald J. Sobol ’48).

Most of

us have favorite children’s book characters. Writing for young people isn’t child’s play—and these Obies know how to speak kids’ language.

By Elissa Gershowitz ’98

Illustrations by Peter Reynolds, Neil Swaab, Terry Widener, Marjorie Priceman, David Slonim, and Hannah Bonner

Chapter-book readers know Judy Moody—a Ramona Quimby for today—and her little brother, Stink. Judy and Stink’s creator is Megan McDonald ’81, and she’s Kind of a Big Deal to the elementary-school set. She’s written eleven Judy books and eight Stink books (plus two in which Judy and Stink share the spotlight), and, oh yes, in 2011 there was a big-screen adaptation, Judy Moody and the Not-Bummer Summer. All told, she has written over 60 books, including historical fiction, girly-girl middle-grade novels, and picture books (“still my first love”).

Oberlin’s creative writing program is what originally drew her, but once at school she studied “everything from Japanese history…to Italian art.” She designed her own major in children’s literature and starting writing what became her first published children’s book—Is This a House for Hermit Crab? (Orchard, 1990)—as an independent study project. College, she says, was “the best years of my life! I even wrote Judy Moody Goes to College (Candlewick, 2010) based on my Oberlin days, because I so loved that time. I became a more thoughtful reader there, a better thinker, and had a lot of encouragement.”

She’s quick to field the tedious question, When are you going to write a real book for grown-ups? “Usually a person, when asked about a book that has greatly impacted their life, will name a book from childhood. We seem to carry a favorite children’s book with us our whole lives; those early books stick with us indelibly.”

When Judy and Stink were a little younger, they could have had play dates with another sister-brother dynamic duo, Ladybug Girl and Bumblebee Boy. Their papa (literally: the characters are based on his kids) is David Soman ’87, who co-writes—with wife Jacky Davis—and illustrates the New York Times best-selling picture book series beginning with Ladybug Girl (Dial, 2008).

Paolo Bacigalupi ’94

Illustrated by Neil Swaab

Swaab created the cover art for Bacigalupi’s two YA novels, Ship Breaker and The Drowned Cities.

Soman was a “Third World studies major at Oberlin, which, oddly, did lead me in a roundabout way to becoming an illustrator. During my junior year I did a semester in Bali, Indonesia. I found myself doing a month-long apprenticeship with a traditional Balinese mask carver, and I realized, as I sat there chiseling wood and trying not to cut my feet (which we used to hold the wood steady), that I was never as happy as I was, right there, making art every day. My focus changed.”

Soman broke into the picture book biz by illustrating Angela Johnson’s Tell Me a Story, Mama (Orchard, 1989). He credits his time at Oberlin for teaching him how to be a critical reader, a skill that’s a real boon for good picture book illustrators. “Understanding how a story works, and what moments are really important, has been at the heart of my choices as an illustrator my whole career.”

Two authors relatively new to the children’s lit world—but where they’ve made a big splash—are Paolo Bacigalupi ’94 and William Alexander ’00. In 2012, Alexander’s debut children’s novel, Goblin Secrets (McElderry, 2012), won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. At school he studied theater and English with a folklore concentration, and he sort of fell into middle-grade fantasy.

“Writing for children caught me unawares. But I’m not too surprised. Adults are very good at fooling ourselves into thinking that we already understand how the world works, but children are constantly running up against things they don’t understand. They expect the world to be weird. And the worlds I write about are pretty weird.”

He credits his studies with helping him world-build: “My time in the Oberlin theater department was influential in all sorts of ways, both in terms of narrative craft and in the subject matter of my fiction—especially Goblin Secrets, a book about a goblin theater troupe. Bits of theater history—the ritual origins of masks and stagecraft, the constant pressure from puritans to ban plays in Shakespeare’s day—have continued to haunt the back of my brain and eventually ended up in that book. I wanted to see how much of the theatrical experience could even fit in a book, and I learned most of what I know about that experience at Oberlin.”

Equally at home in the speculative-fiction realm is Paolo Bacigalupi ’94. His children’s book debut, a young-adult dystopian sci-fi novel called Ship Breaker (Little, Brown, 2010), won the 2010 Printz Award—the top prize in YA fiction—and was a National Book Award finalist. Bacigalupi had already enjoyed success as a writer for adults with his debut novel, The Windup Girl (Night Shade, 2011), winning the Hugo and Nebula awards. However, writing wasn’t always in his plans.

At Oberlin, he studied East Asian studies and Chinese language: “I thought I was going to go into business in China. But studying things like Chinese and economics and environmental studies ended up informing a great deal of my work. I’m interested in how cultures come together, who wins and who loses when they do. I’m particularly interested in how present-day decisions will impact future generations, and my Oberlin studies provided a foundation for me as I continue to research topics for my books.”

Another author who came into young-adult publishing from the grown-up side is Tofa Borregaard ’98. An archaeology major with minors in anthropology, geology, philosophy, and classics, she holds an MS in archaeological materials and an MA in anthropology with a focus on archaeological analysis. Writing as Gail Carriger, Borregaard is well-known as the New York Times bestselling author of the Soulless books, a supernatural romance/speculative-fiction/steampunk/humor series about a spirited, suspiciously autobiographical lady in an alternate-Victorian London who can neutralize the powers of werewolves and vampires.

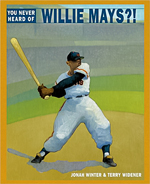

Jonah Winter ’84

Illustrated by Terry Widener

“I have Jonah as a Renaissance man, which he truly is,” says Widener, who collaborated with Winter on You Never Heard of Willie Mays?!.

Her nom de plume is more of an alter ego. She shows up at book signings in full Gail regalia, cat-eye glasses, vintage threads, and all. It’s very theatrical in a particularly Oberlin sort of way. In 2010, Soulless won an Alex Award, a prize given to books originally published for adults that have special appeal for teens. In 2013 she tried her hand at young-adult fiction, setting her Finishing School series (Book One: Etiquette & Espionage) in the same world as the Soulless books, but several years earlier. “I always wanted to write YA; it’s the genre I most love to read. I like the length of the books and the voice of the characters.”

It’s not just fiction writers having all the fun. Jonah Winter ’84 is well-known both as an author of poetry for adults and of picture book biographies, including New York Times bestseller Barack (Tegan/HarperCollins, 2008), Just Behave, Pablo Picasso! (Levine/Scholastic, 2012), and Sonia Sotomayor: A Judge Grows in the Bronx / La juez que creció en el Bronx (Atheneum, 2009), among many others.

“I could not feel more proud—and lucky—to be a picture book writer. I’ve got my beautifully illustrated, 32-page flag flyin’.” He is also a sometimes illustrator, and art from two of his books was recently displayed at a gallery in Oberlin. “The same political tendencies that motivated me to come to Oberlin have motivated the very leftist, politically oriented nonfiction I write for children: books about Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas [Gertrude Is Gertrude Is Gertrude Is Gertrude (Atheneum, 2009)], people who’ve endured bigotry, manual laborers, nonconformists, artists, musicians, progressive political activists, social reformers, and rebels in general.”

Tanya Lee Stone ’87 wears her heart on her sleeve in her social-issues-based nonfiction. Her almost 100 books for kids include Courage Has No Color: The True Story of the Triple Nickels, America’s First Black Paratroopers (Candlewick, 2013), Almost Astronauts: 13 Women Who Dared to Dream (Candlewick, 2009), and The Good, the Bad, and the Barbie: A Doll’s History and Her Impact on Us (Viking, 2010).

These books bring little-told stories to light for teens through lively narration, fascinating interviews, and other primary-source documentation.

Tanya Lee Stone ’87

Illustrated by Marjorie Priceman

Priceman illustrated Stone’s Who Says Women Can’t Be Doctors? The Story of Elizabeth Blackwell.

Picture book biographies Who Says Women Can’t Be Doctors? The Story of Elizabeth Blackwell (Holt, 2013) and Elizabeth Leads the Way: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Right to Vote (Holt, 2008) show off Stone’s feminist side: “Oberlin had a profound effect on me as a developing feminist, and many of my books have a feminist bent and are focused on highlighting the lives and accomplishments of both women and people of color. Oberlin heightened my awareness of the world outside my own front door, and I take that with me on every research project on which I embark.”

Stone and Winter both have worked as children’s book editors, Stone as managing editor of Blackbirch Press and Winter for Knopf and Random House. Author Susan Goldman Rubin ’59 has a unique rapport with her own editor at Chronicle Books, Victoria Rock— a 1983 Oberlin grad. Rock helped launch Chronicle Books’ children’s list, now celebrating its 25th anniversary.

She and Rubin have worked together on a number of artist biographies for middle-graders and teens including Wideness & Wonder: The Life and Art of Georgia O’Keeffe (Chronicle, 2011) and Delicious: The Life & Art of Wayne Thiebaud (Chronicle, 2007), along with the Modern Masters board book series for preschoolers and the forthcoming Everybody Paints: The Art & Lives of the Wyeth Family (Chronicle, 2014).

“My job is to help the authors and artists I work with find clarity in their work and help them create something that is suited to the audience they want to reach,” says Rock. “It is really about helping to polish an idea…mostly about asking ‘What if?’ And Oberlin has always been a place that has attracted and encouraged the curious. So when I am lucky enough to work with an author who comes out of that same environment, we share the same inclination to explore.”

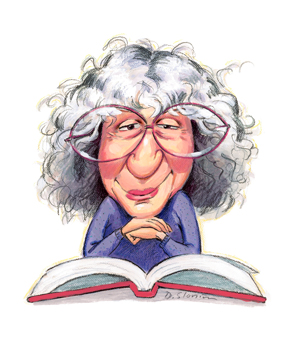

Susan Goldman Rubin ’59

Illustrated by David Slonim

An artist herself, Goldman Rubin also works with other illustrators for her books, including Slonim, who illustrated Haym Salomon: American Patriot.

An English major, author Rubin “loved art and took some studio classes so that I could keep drawing. I had no intention of being a writer. I wanted to illustrate children’s books. To my surprise, editors were as interested in my writing as my art.” She read “dozens and dozens of picture books to understand the structure,” and later taught classes in writing and illustrating children’s books to adults.

Rubin also writes social-history-leaning picture-book biographies—à la Winter and Stone—such as Irena Sendler and the Children of the Warsaw Ghetto (Holiday House, 2011) and the forthcoming Freedom Summer, 1964 (Holiday House, 2014) for which she interviewed Oberlin alums who were civil rights activists in Mississippi in 1964. She’s also excited to be working on a biography of noted composer Stephen Sondheim, with his approval, for teens.

“After a year of research and interviews with many of Sondheim’s collaborators, I recently interviewed him at his home. It was an incredible, enlightening experience. Preparing for that interview reminded me of preparing for my orals senior year at Oberlin!”

Hannah Bonner ’78 and Emily Goodman ’78 bring a passion for science to their writing. Author/illustrator Bonner, a studio art major who lives in Palma de Mallorca, Spain (where she grew up), is best known for her trilogy of “cartoon history” books, published by National Geographic Children’s Books, about life before dinosaurs: When Dinos Dawned, Mammals Got Munched, and Pterosaurs Took Flight (2012), When Fish Got Feet, Sharks Got Teeth, and Bugs Began to Swarm (2007), When Bugs Were Big, Plants Were Strange, and Tetrapods Stalked the Earth (2004).

“We seem to carry a favorite children’s book with us our whole lives; those early books stick with us indelibly.”—Megan McDonald ’81

Goodman is a writer and poet who has worked as a gardener at the Prospect Park Zoo in Brooklyn. Her picture book debut, Plant Secrets (Charlesbridge, 2009), is a nonfiction look at botany for kids. Both authors agree that distilling complex science into something understandable for kids while still maintaining accuracy is a major challenge. According to Goodman, “That’s the main task of science writers. There are twin concerns of accuracy and aesthetics—keeping the presentation clean, simple, beautiful, and true. I wanted to make the text as eloquent as a poem, and not lose rhythm and power in the quest to make it completely accurate. It was a tricky balance, but I’m proud of the result.”

Bonner says: “Images are key. As author and illustrator, I get to decide what to show as images and what to convey as text, and the two are closely linked. The beauty of image is that there is no need to simplify: children and adults alike can take in a lot of visual information and can choose to observe more or less detail, or focus in on only one aspect of an illustration. The other really important key for me is humor.”

Bonner’s comic-style illustrations are cartoonish and light, but they convey real information. “I also always loved nature, and by the time I went to college I was torn between art and biology. Back in the ’70s, I had never heard of scientific illustration as a possible career choice. If I had, I might have realized that I could combine my two loves and double majored. Luckily, over the years, I’ve managed to combine my two loves in the work I do.”

And what better job is there than creating books that will be enjoyed by kids for years to come?

Elissa Gershowitz ’98 holds an MA in children’s literature and is senior editor of The Horn Book Magazine, a children’s book review journal.

Hannah Bonner ’78

Illustrated by Hannah Bonner

Bonner thinks about when dinos

dawned, fish got feet, and bugs were

big, among other things.

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.