Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Fall/Winter 2007 Vol. 103 No. 2

Losses

Manfred J. "Fred" Lassen

Oberlin College’s Protestant chaplain for the past two decades, died at his Oberlin home in December while on medical leave from the College. Rev. Lassen was 67 and had been suffering from heart disease. He leaves two sons, Frederick Lassen ’91 and Jonathan Lassen ’94.

Marjorie Witt Johnson ’35

Dance Educator

A pioneer of modern dance and founder of the Karamu Dancers in Cleveland, Marjorie Witt Johnson first became enchanted with dance at Oberlin, which she chose for its openness to blacks and women. Struggling with her grades, she actually thought about dropping out, but then found hope in modern dance. After college, she directed a dance camp for inner-city girls, which later became the Karamu Dancers at the Karamu House. The Cleveland troupe eventually made its way to the 1940 World’s Fair in New York.

In 1945, Johnson earned a master’s degree in social science administration at Western Reserve University. She took her talents to Hull House in Chicago, to public schools in North Carolina, and to the Atlanta School of Social Work. Returning to Cleveland, she developed dance and creative arts programs for middle and elementary school children. "For Marjorie, it was the importance of how the dance was elevating the consciousness, the spirit, and motivating the youth to know they could excel in whatever they wanted in life," said Dianne McIntyre, a noted composer who lives in Cleveland.

In 2005, the Cleveland Contemporary Dance Theatre presented Daughter of a Buffalo Soldier which celebrated the life and legacy of Johnson, who was born the daughter of a Buffalo Soldier in Wyoming. The piece involved Oberlin students and was performed at Karamu House and at Oberlin.

Johnson received countless awards over the years, including the 1999 Governor’s Awards for Arts in Ohio, the Cleveland Arts Prize in 1999 for Distinguished Service to the Arts, the 1997 Sankofa Award from the National Black Storytellers, and the Oberlin Alumni Distinguished Service Award. She died July 19 at age 97, leaving a daughter.

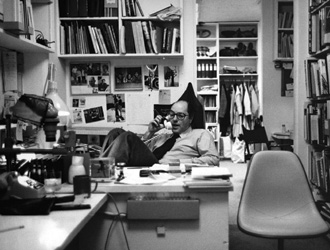

André Emmerich ’44

Eminent Art Dealer

André Emmerich was not a typical new student when he matriculated at Oberlin in the autumn of 1941. Born in Germany and raised in Amsterdam, he had emigrated with his family to New York City in 1940, finishing high school there at age 15. The grandson of a noted Paris art dealer, André arrived on campus a sophisticated young man, fluent in Dutch, German, French, and English.

Years later, after he had become one of the world’s top art dealers, James Yohe, a friend who heads Ameringer-Yohe Fine Art in Manhattan, asked how such an urbane teenager had taken to life in small-town Ohio. "He smiled at me and said, ‘I loved it. For the first time in my life, I was exotic,’" says Yohe, whose son, Yujin, is currently a second-year Oberlin student.

That dry wit and affection for Oberlin stayed with André throughout his life. He graduated with a BA in history in 1944, at age 19, after studying with Frederick Artz, Robert Samuel Fletcher, and Howard Robinson. He also worked under Clarence Ward at the Allen Memorial Art Museum, typing catalog cards, a job he got because of his linguistic prowess.

After graduation, André lived in Paris for 10 years, working as a writer and editor. But art was his true passion. In 1954, he returned to New York and opened the André Emmerich Gallery on Madison Avenue. The gallery eventually expanded to include branches in SoHo and Zurich. In it, André championed Color Field painting, showing works by major artists such as Anthony Caro, Sam Francis, Helen Frankenthaler, Al Held, David Hockney, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski. He also organized important exhibitions of pre-Columbian art and wrote two acclaimed books on the subject.

"I think a good art dealer’s motto should be credo ergo exposito: "I believe, therefore I exhibit," André wrote in his memoir My Life With Art, published in 2003. He also believed in Oberlin’s tradition of inclusion. In the 1950s and ’60s, when leading galleries had quotas for female artists, he mounted shows by Ms. Frankenthaler, Beverly Pepper, Anne Truitt, Miriam Schapiro, and Judy Pfaff.

André served two terms as president of the Art Dealers Associa-tion of America, was active on its board, and was regarded as one of the most eloquent spokesmen not just for the association, but for art. His gallery was sold to Sotheby’s in 1996, but he continued to direct it until 1998. He passed away in Manhattan on September 25 at age 82, and is survived by his wife, Susanne, and his sister, Nicole Emmerich Teweles ’47, of Milwaukee.

Throughout his career, André was involved with Oberlin, serving on the Allen’s Visiting Committee in the 1980s and ’90s. "He was a very elegant man," says Douglas Baxter ’72, a fellow Visiting Committee member and president of PaceWildenstein, a top New York gallery. "A group of us had dinner with him last spring. He was not in good health but was still so gracious and elegant and curious about what was going on at Oberlin. André loved Oberlin."

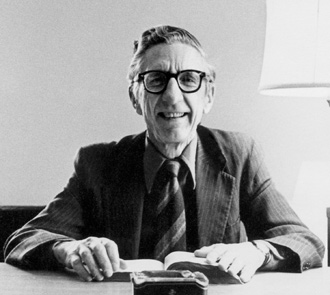

Dr. F. Champion Ward ’32

Lifelong Educator

On July 2, 2007, Oberlin Emeritus Trustee Dr. F. Champion Ward, past dean of the College at the University of Chicago, Ford Foundation vice president, and chancellor of the New School for Social Research, died at his home in North Branford, Connecticut. He was 96 years old.

Ward’s career spanned the postwar course of American and international education, beginning with his tenure as the dean of the innovative College of the University of Chicago in 1947; his years advising the governments of the newly independent nations of Asia, Africa, and the Middle East; and his work as the Ford Foundation’s vice president for education and research.

Ward was born on December 30, 1910, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, but spent his boyhood in Oberlin, where his father, Clarence Ward, was head of the College’s art department. After acquiring a master’s degree in philosophy in 1936, he went on to earn his doctorate as a Sterling Fellow at Yale University. From 1937 to 1945 he taught philosophy and psychology at Denison University, and as associate dean trained officers for the Army’s de-Nazification efforts in Europe.

After the war, Ward joined the faculty of the nascent Hutchins College at the University of Chicago. Within two years he had been appointed dean of the college. For seven years, he and Chancellor Robert Maynard Hutchins, OC ’17, whose Yale lectures six years earlier had fired Ward’s commitment to elevating American higher education, fought side-by-side in the battle between their new interdisciplinary college with its core humanities curriculum and the university’s departmental faculties. The principles and practices that have evolved from their innovations continue to influence American higher education.

After Hutchins’ departure, Ward took a leave from Chicago to join the Ford Foundation and serve as educational consultant to the government of India. From 1954 to 1959, during which Chicago made him William Rainey Harper Professor of the Humanities, Ward lived with his family in New Delhi, India, where, at a time of Red Baiting back home and Cold War clumsiness abroad, he earned Indian educators’ trust and respect by refusing to take any action until he had spent a year immersing himself in the country’s culture and history. A gentle critic of the precipitancy with which American philanthropies behaved in developing countries, he was soon enlisted to advise the governments of Burma, Turkey, and Jordan as well.

In 1959, Ward began a four-year stint as director of the Ford Foundation’s Overseas Development Program for the Middle East and Africa, through which he traveled extensively. In 1963, he was appointed deputy vice president for international programs, and three years later became vice president for education and research. During the next five years he also served as chairman of the White House Task Force on the Education of Gifted Persons, and as a member of UNESCO’s Inter-national Commission on the Development of Education.

From 1959 to 1978 Ward also served as a trustee of his alma mater, Oberlin College. Ward’s dedication to Oberlin was almost literally lifelong. As the child of a professor, a student, an alumnus, a trustee, and recipient of an honorary degree, over nine decades he observed and helped to guide Oberlin’s evolution into one of the premier colleges in the country, and himself embodied the institution’s ideals of service, humanity, and respect for other peoples and cultures. Not only did he and his sister Helen attend Oberlin, he married an Oberlinian, and all three of his children, two of his daughters-in-law, and two of his grandchildren are alumnae.

After his retirement from the Ford Foundation in 1977, Ward served as a consultant at the World Bank, UA-Columbia Cable Television, the Association of American Universities, and the Connecticut Board of Higher Education; as well as the Ford, Hazen, Edna McConnell Clark; and Mrs. Giles Whiting Foundation. From 1978 to 1981 he was the "midwife," as he put it, at the birth of the MacArthur Foundation’s "Genius Grants."

In 1980, Ward was appointed chancellor and acting dean of the Graduate Faculty of the New School for Social Research, which he worked to help restore to its founding, interdisciplinary principles. He also served on the Greenwich, Connecticut, Board of Education, where he successfully fought to retain the town’s neighborhood schools. He was a member of the editorial board of the Journal of General Education, editor of The Idea and Practice of General Education, and contributor to Humanistic Education and Western Civilization and The Knowledge Most Worth Having.

By the time of his death, Ward had been married to Duira Baldinger Ward ’34 for over seven decades. Together they raised three children: historians Geoffrey C. ’62 and Andrew Ward ’68, and children’s welfare advocate Helen Ward ’70. He was a fond patriarch to a proliferating clan, which came to include grandchildren Nathan ’85, Garrett, Kelly ’88, and Jake Ward; Casey Ward Federico; Danny and Katie Lowe; and great-grandchildren Nicholas and Nina Ward.

A devotee of Plato and George Santayana; an empathetic man with a self deprecating wit; an amused foe of pomposity and hypocrisy; a fierce competitor at tennis and eight ball; an avid baseball fan; a lover of the English language; and a keen observer of politics foreign and domestic, Ward enjoyed nothing more than comparing notes with Dui and discussing with young people the state of the world.