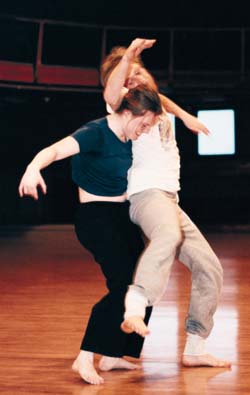

Beginning Contact Improv students learn movement and dancing techniques. |

"If you do not feel there is anything wrong with education at Oberlin-if you weren't disappointed and bored by a freshman year which was as fresh and exciting as a high school lecture sandwiched between four times the high-school reading load; if you aren't frustrated by a medieval lecture system that should have died with the invention of the printing press; if you aren't turned off by humanistic disciplines which somehow fail to relate to you as a human and by social sciences which only infrequently help you relate to the social events and injustices that every day overflow into your life-then the Experimental College isn't for you."

With this 1968 commentary in the Oberlin Review, student Paul Tamminen '69 exposed the culture that originated Oberlin's Experimental College. ExCo-as it since has been nicknamed-started offering courses that fall, a time when many students denounced Oberlin's then-traditional education. Tamminen demonstrated the fervor of the debate in a 1968 Homecoming report to alumni. "In numerous ways Oberlin education is misdirected, or out of date, and thus harmful to the best interests of both students and our society," he wrote. The previous April, Tamminen and a band of students had received approval from the College of Arts and Sciences to found ExCo, a category of courses organized and conducted by students. Although rare today, experimental colleges were popular in the 1960s and early '70s, and ExCo's founders created the program as a laboratory for pedagogical changes they hoped would sweep through the college. |

Its premise remains the same today: in place of professors, students and community members coordinate interdisciplinary courses on topics of interest to them. The coordinators are rarely experts, but they must demonstrate an ability to lead a class through the subject matter. Lectures are replaced with small discussions or group activities held in a lounge, seminar room, or apartment, and the entire curriculum is run by a student committee.

It was a bold program with a revolutionary agenda, and some believe it led to innovations within the regular curriculum that fall. Faculty voted to offer a group of ad hoc courses responsive to current social and political conditions. The first, Modern Black Literature, was taught by English instructor John Hobbs in the spring of 1969.

Other innovations followed. The first Winter Term occurred in January 1969, followed by the credit/no entry option that was pioneered in a way by ExCo's grading experiments. Distribution requirements changed a few years later.

Throughout it all, ExCo thrived. In a report to the college's Educational Plans and Policies Committee in 1973, ExCo Chairman Stuart Robbins '75 reported that in discussions with chairs of other Experimental Colleges around Ohio, it was determined that the traditional lifetime of an organization such as ExCo was approximately three years. At most colleges, the novelty of the program wore off and student interest waned.

"The Oberlin Experimental College is a striking exception to that pattern," Robbins declared, and with good reason. The number of classes and participating students had grown steadily over the first four years. Only five ExCo courses of the 22 offered in 1968 were permitted to grant college credit, and of those, students were limited to taking one.

ExCo grew to 53 courses in 1973, and, as restrictions lessened over the years, grew to be the college's largest department. Today, ExCo offers an unlimited number of courses for credit, and students can count up to five hours of those credits toward graduation. With 106 courses, the program reached a new high last spring.

These days, instructors use a range of teaching methods and deal with current topics and affairs. The educational policies advocated by the founders of ExCo have become intertwined with Oberlin's "traditional" curriculum-classes within the history, sociology, women's studies, and politics departments deal with issues today that were raised in experimental courses of the '60s and '70s: Urban Politics, The American Indian, Issues in Women's Health, and Society and the Individual: A Gay Studies Perspective. Even departments and programs-African American, women's, Jewish, and environmental studies-started as, or were supplemented by, ExCo classes.

"ExCo began with the idea that there was something seriously wrong with education at Oberlin," said ExCo committee member Mark Carr '87 in the Oberlin Review. "I think ExCo's role has changed and that's how the '60s, '70s, and '80s were different. No one is putting down Oberlin's education any more."

Within a few years of its birth, ExCo was transformed from a revolutionary concept to a complimentary alternative to the college's regular curriculum. Once intended to challenge Oberlin's traditions, ExCo became an Oberlin tradition.

Scott Maier '78 posed this issue in a 1976 article in the Oberlin Alumni Magazine. "Since its inception eight years ago, the role of ExCo as a model for educational reform has become less important. Institutional changes at Oberlin have quieted student demands for greater relevance, more interaction, and alternative grading procedures. The dissenting function of ExCo has taken a back seat to its fundamental purpose of providing Oberlin students with the opportunity to structure and participate in courses that are not offered in the College or Conservatory curriculum."

Peter Hlinka '00, a member of this year's ExCo committee, values the opportunities to explore new topics in small settings. "The programs that ExCo supports are still marginalized programs that cannot be found under the rubric of classes commonly taught at colleges and universities," he says. "They deal intimately with subject matter that is relevant, but not, for whatever reason, widely taught."

|

Courses involving volunteer work have been a popular way of mixing community service and academic study. Martial arts, crafts, pop culture, meditation, sport, and language classes are offered nearly every semester, while courses such as Gilbert and Sullivan, Steel Drum Ensemble, Modern Dance, and Improv Comedy Technique tap into and help foster Oberlin's creative community.

Jerry Greenfield '73, co-founder of Ben and Jerry's Homemade Ice Cream, Inc., once shared with OAM his experience in a Carnival Technique ExCo. Coordinating the course was his classmate Bill Irwin '73, now a famous actor-mime-clown who has appeared on Broadway, television, and in films. "Bill taught me how to do a cinder-block smash on the bare belly of my partner, Habini Ben Coheni, the noted Indian mystic, with a sledgehammer," Jerry says. "We're talking practical knowledge you can use in the outside world. I also learned how to eat fire, and I've done both in public." ExCo also became the repository of student interest in education and communications after the college eliminated those departments. Topics range from the community service-based O.C. Mentors and the theory-based Progressive Education and the New Visions School Movement to current media commentary such as Sociopolitical Evaluation of The Simpsons and From Snow White to Brown Skin-The Disney Films, with each adding their own spin to the disciplines. |

The Oberlin Aid to Strays practicum focuses on animal care and requires students to volunteer with campus and city dog/cat programs, fundraising efforts, and community education. |

Coordinating and leading a course is itself a lesson in pedagogy, as is membership on the student-run Experimental College committee that oversees all major decisions: approving coordinators, classes, and the amount of credit a course can offer. And, as with any student organization, the program has endured moments both good and bad.

Mark Carr remembers a low point in 1984. "The entire experienced committee graduated, leaving Will (Thomas '87) and me," Carr says. "Suddenly I was running this college."

Carr and Thomas, as did others before and after them, carried ExCo forward. While student interest in teaching and taking courses is always high, running the program inevitably falls to a handful of student volunteers. They are the ones who deal with ExCo's critics, those who point out the frivolity of particular topics and maintain that the courses are reputed to be too easy. Some educators today question the outcome of ExCo courses and the appropriateness of awarding credit for classes taught by students.

Yet the committee perseveres, always evaluating and reinventing what ExCo is. In 1977, when the committee suspected that interest in educational alternatives dissipated and students seemed more interested in receiving easy credit, they overhauled the application procedure.

When I was a member of the committee in 1994 and '95, we tightened ExCo's credit-granting and coordinator-approval policies yet again. We also offered more support for coordinators through a manual and pedagogical workshops with faculty members.

Since then, a student-worker position has been added to keep track of the classes. ExCo has always scrambled for money, and with joint funding from student-activity fees and the college's dean's fund, the committee hired part-time clerical and administrative support.

Students from Grinnell College initiated their own experimental college last year after seeking help from Oberlin. Their program is basically a copy of ExCo.

Imitation, it is said, is the highest form of flattery.

Mark Graham '97 is a staff writer in the Office of College Relations. He was a member of the ExCo committee from 1994 to 1996 and is coordinating his third ExCo class, The Cinema and Culture of Spielberg, this spring.

- On to more ExCo images

- On to Wired for Culture

- Back to the OAM May 1999 Table of Contents