Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Spring 2007 Vol. 102 No. 4

Portrait of a President

Portrait by Sarah Belchetz-Swenson '60

Portrait by Sarah Belchetz-Swenson '60

President Dye greets new graduate Reginald Patterson ’05 and his family during a post-Commencement luncheon at her home.

President Dye greets new graduate Reginald Patterson ’05 and his family during a post-Commencement luncheon at her home.

Nancy Dye’s support of athletics will be among her legacies.

Nancy Dye’s support of athletics will be among her legacies.

The president greets 2006 graduating senior Hang Do.

The president greets 2006 graduating senior Hang Do.

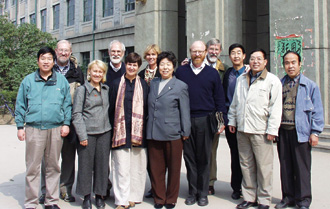

Nancy and Griff Dye visited northern China in 2000.

Nancy and Griff Dye visited northern China in 2000.

Nancy and Griff pose with Obirin University President Toyoshi Sato and his wife in 2005; Dye accepted an honorary doctorate from the school.

Nancy and Griff pose with Obirin University President Toyoshi Sato and his wife in 2005; Dye accepted an honorary doctorate from the school.

Nancy Dye visited Iran in 2005 to begin talks about resuming educational exchange programs between the U.S. and Iran.

Nancy Dye visited Iran in 2005 to begin talks about resuming educational exchange programs between the U.S. and Iran.

The president spoke to high school students in Pakistan during a two-week recruitment trip last fall.

The president spoke to high school students in Pakistan during a two-week recruitment trip last fall.

President Dye with members of the Oberlin Alumni Council last fall: Alumni Association President Wendell P. Russel, Jr., ’y1, Andreas Goldner ’56, and Dwan Vanderpool Robinson ’83

President Dye with members of the Oberlin Alumni Council last fall: Alumni Association President Wendell P. Russel, Jr., ’y1, Andreas Goldner ’56, and Dwan Vanderpool Robinson ’83

The President with the Board of Trustees Chair Robert Lemle ’75.

The President with the Board of Trustees Chair Robert Lemle ’75.

Celebrating a recent $4.5 million grant to Oberlin from the Bonner Foundation.

Celebrating a recent $4.5 million grant to Oberlin from the Bonner Foundation.

Nancy Dye arrived in Oberlin 13 years ago much like a wide-eyed freshman. She was a prize recruit—bright and accomplished and eager for the Oberlin experience. Her long and very successful tenure as president, the first woman at the helm of the College, became, for her, an Oberlin education. Before she steps down at the end of June, President Dye will receive an honorary degree from Oberlin. It’s only fitting: it’s as much a commencement as a retirement.

Nancy Dye leaves a changed person. Worldlier (“Literally. I take far more interest in the affairs of the world than I ever did before in meaningful ways.”) and wiser, her ability to lead a diverse and contentious institution tempered in the daily heat of decision-making and the occasional inferno of controversy.

She leaves Oberlin a changed institution as well, yet leaving intact its mission and unique sense of self. Says Danette DiBiasio Wineberg ’68, a College trustee and former president of the Oberlin Alumni Association, “While Nancy was not from Oberlin, she is ‘of’ Oberlin—what people call an ‘Obie.’ She ‘gets it’—what makes Oberlin special and unique —and she has celebrated and capitalized on that. What I recall in particular is her leadership style of inclusiveness and consensus building.”

President Dye changed the College’s course, arriving during what was considered a difficult period in the institution’s history: morale was low, the deficit was high, and the future was uncertain. Today, the place is demonstrably much stronger than when she found it: financially, academically, and, in the Oberlin tradition, in its deep civic engagement with the town of Oberlin, the welfare of its residents, and with the world at large.

She led a successful capital campaign, the College’s largest ever, and during her tenure Oberlin’s endowment increased by more than $490 million to its current value of $750 million. The College is now much more selective in accepting students, and the number of accepted students who choose to come to Oberlin—and those who stay on to graduate—has grown significantly. A generation of new, highly talented professors has been hired under President Dye’s watch, and Oberlin has become a far more international—and internationalist—campus. The Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies, still the greenest building on any American campus, was approved for planning and construction early in her presidency. And she herself sees the new 344,620-square-foot Science Center as one of her most important contributions; she stresses that maintaining Oberlin’s leadership in undergraduate science education is essential to Oberlin’s academic excellence.

President Dye has also led two successful planning exercises: “Broad Directions for Oberlin’s Future” in 1996-97 and “A Strategic Plan for Oberlin College” in 2004-05. In each, a team of alumni, faculty, administrators, trustees, and students developed a clear mission for the College.

“The 2005 plan is one of the high marks of her presidency,” says longtime Trustee George Bent ’52. “Very often with a strategic plan, the process is as important as the product. She made it happen and created, I believe, a process that almost everyone came to respect. And the result is stunning. The plan could chart the course of Oberlin’s future. It’s not just sitting on the shelf occupying pretty space; it’s a working document.”

President Dye’s creation of an ombudsperson’s office and her support for Oberlin’s ambitious student mediation program and the Oberlin College Dialogue Center show her commitment to finding more effective models for dealing constructively with disagreement and campus conflict. Athletics are no longer a laughing matter. And the College’s commitment to the community has been strengthened immeasurably due to her efforts, including creation of a full scholarship for Oberlin High School graduates who are admitted to the College.

“I hope I leave Oberlin a better and happier place than I found it,” she says simply.

According to many faculty members, trustees, alumni, and students, she will.

“Nancy brought Oberlin out of a troubled time of self-doubt and uncertainty, and delivered it to a new period of possibility where everyone knows we are a great institution and expects us only to improve,” says Ben Lee, assistant professor of classics.

Robert Lemle ’75, chair of the Board of Trustees, says, “Oberlin has, by any measure, made enormous progress. Because of her, Oberlin has been doing well and is poised for continued success.”

President Dye was among the first to embrace Oberlin’s “Fearless” marketing campaign last year. “I love ‘Fearless.’ I think it is very appropriate for Oberlin. Critics of ‘Fearless’ see Oberlin capitulating to the market-driven imperatives of contemporary capitalism. But Oberlin has always had to pay attention to how the world thinks of it. Yes, we are a unique and very special place, but we must communicate those special qualities. We have to work harder to get our own message out, and our message can’t sound like all the others.

“Oberlin is often fearless—intellectually fearless, socially fearless, and artistically fearless,” she says. “It could be even more fearless. Oberlin has always been ahead of the curve in addressing the social and cultural issues facing this country and the world. And if the ‘Fearless’ campaign doesn’t work—and frankly this is kind of fearless—we scrap it and say, ‘Let’s do something else.’ You can’t please everybody.”

The Student Perspective

President Dye’s tenure on campus has been pleasing to many, including Oberlin’s most important resource: its students.

“I think that I have been accessible to students, and that has also been a great pleasure of the job. I’ve learned a lot about how very smart, thoughtful, and engaged 18- to 22-year-olds on a very diverse campus see their own societies and the international order,” she says. “One sees a lot of undergraduates over 13 years, and I have been fortunate to get to know well some in each graduating class. They have taught me a lot about environmental sustainability, for example, and how important it is to them. Their lived commitment to finding ways to reverse the course of global warming makes me confident about the future of the earth.”

She did more than learn. She listened. And acted.

“President Dye nurtured the dreams and talents of each person she touched,” says Senior Class President Matthew Kaplan ’07. He recalls being a gangly freshman and scheduling a meeting with her. “I realized that she really cared for her students and had a genuine willingness to listen. President Dye spoke with vigor and optimism, and I left the meeting with the feeling that I could take on the world.”

He also left with the feeling that he could take on the College’s administration.

“President Dye spent countless hours gathering student opinion from the Student Senate,” adds Kaplan. “Each month, she would meet with the Senate to discuss hot-button campus issues. These ranged from investment transparency to environmental LEED certification to the role athletics should play at Oberlin. She created a space for honesty and openness during these meetings. As a student senator, I never felt I had to hold my tongue or spin my words. It was clear that she valued direct lines of communication and open dialogue.”

The question of whether athletics should be more important to Oberlin was one in which the president, standing up to faculty and student critics, showed leadership.

“The Oberlin athletics program was in disarray when Nancy Dye arrived in 1994,” says Kev O’Connor ’51, past president of the Heisman Club. “She recognized that if Oberlin wanted to attract a diverse student body that included aspiring student athletes, it would require a strong athletic director, dedicated and inspirational coaches, and support of the administration and alumni. Through her leadership and commitment, she leaves a revitalized athletics program, a reinvigorated Heisman Club, and a football team that can boast of a recent 5-5 season.”

Adds Dye: “Somehow, many people at Oberlin have had a hard time seeing how important athletics are to many students. We’ve always said at Oberlin that it is important for students to be passionate about something. They are passionate about all manner of things: learning Chinese, the oboe, theater, and, yes, some are passionate about football. People have individual paths and interests, and Oberlin, which works hard to respect every one of its students individually, has begun to realize this fully with respect to its athletes.”

The Education of Nancy Dye

In President Dye’s most recent remarks to alumni, faculty, students, staff, and trustees at the unveiling of her presidential portrait, she gave thanks for all she has learned.

“The most important part of my education has been an education in appreciating human diversity. Oberlin is a very diverse place in all the ways that people can be diverse, and part of the job of being Oberlin’s president is to foster and nurture that diversity. This has been an incredibly rewarding part of the job and also a great part of my own education: how to live in and help build a robust pluralistic community. My comfort zone is much more capacious than it was when I arrived.”

Robert Lemle agrees.

“Nancy has always had a special understanding of the central equation of Oberlin’s experience: That academic, artistic, and musical excellence at Oberlin is animated by—indeed, dependent upon—its commitment to diversity,” Lemle said in a recent speech. “She has always interpreted diversity broadly, from honoring Oberlin’s long tradition of racial and socioeconomic access to championing social inclusion; from encouraging respect for differing points of view and the free exchange of ideas to promoting the importance of internationalism.”

Appreciating diversity also means managing conflict, which in the months leading up to her retirement announcement were revved up between the president and some of the faculty, as well as those who were not in favor of the “Fearless” campaign.

President Dye views it as another opportunity to learn.

“I’ve learned a lot about dealing with conflict at Oberlin because there is, on a campus like this, a great deal of contention,” she says, her sentence punctuated with a jovial laugh. “I think I was reasonably comfortable with conflict on campuses before I came here, but I have learned a lot about how to deal with conflict at Oberlin. And I don’t just mean in terms of conflict resolution, but how to deal with conflicting views and be comfortable with that.”

Conflict or not, a president must be decisive.

“One of the things I have learned for myself is to see and think about the big picture in ways that I could not when I first came to Oberlin. And by big picture, I mean really big picture,” she says. “One of the tendencies of any institution or organization is to be bureaucratic, to focus on little things instead of big principles. All institutions resist change by saying, ‘we have always done it this way.’

“I have found over the past 13 years that the most important thing is to be humane,” she adds. “That may sound trite, but it isn’t. I have thought more deeply about how people feel, and that has changed me for the better. Not all decisions necessarily will be perfectly humane. We have to deny tenure; we have to suspend students. But I think that seeing a bigger picture often rests on making a humane decision rather than a bureaucratic one.”

Oberlin City Council President Daniel Gardner ’89, who served as the first director of the College’s Center for Service and Learning, says President Dye manages to engage in constructive debate without turning opponents into adversaries. He saw her adroitly handle what seemed to be an impossible job.

“There are many constituencies to attend to, each of which feels that the institution is ultimately and uniquely theirs,” Gardner says. “Face it. Being Oberlin’s president is a political job. Compara-tively speaking, college politics seems more trying than actual politics. As city council president, I know who my enemies are. I know alliances are temporary, and people aren’t afraid to announce their selfish interests. At the College, the desire for control and power is more repressed, and therefore harder to deal with. Of course, I’d trade a fundraising kielbasa dinner at the Polish-American Club for a reception at the Getty Museum any day.”

But President Dye had the resolve to deal with the politics.

“Nancy never shied from a fight if circumstances required it,” Gardner says. “She’s a very warm, likable person, but I know several people who, to their peril, mistook this quality for weakness. That outrageous, nearly goofy laugh of hers belies a tough and tenacious core.”

Professor of Organ James David Christie says the president’s decisions were always made with Oberlin’s best interests in mind.

“She has had to make some very tough decisions over the years, as college presidents often must, and I always respected her decisions and I appreciated how she thought things through,” says Christie. “It is not easy to deal with a faculty that governs the institution, and there is no one who could make the faculty 100 percent happy all the time. For me, and I believe for the great majority of the Conservatory faculty, Nancy has been excellent.”

David Boe, professor of organ and chair of keyboard studies, saw firsthand President Dye’s deft touch with handling com- plicated issues when he was called to serve as dean of the Conservatory for a semester.

“Given all the cross-currents of conflicting demands made on the president, I was impressed with her ability to maintain her sense of balance and fairness,” says Boe.

Joyce Babyak, associate professor of religion, praises President Dye’s sensitivity: “I have always been impressed by the remarkable dignity with which Nancy runs the General Faculty meetings. Early on in my time here, the College’s Sexual Offense Policy and Procedures had to be revised, and Nancy led a charged faculty discussion on the matter. She displayed vision and courage and, above all, concern for the well-being of the students at that meeting.”

Retirement and Moving Forward

The bumps can wear on a president, though, and President Dye says she came to the conclusion in August that retirement felt right. “Why am I leaving? Because it’s time,” she says.

But even in retirement, President Dye is displaying her commitment to Oberlin. She and her husband, Griff, have purchased an older home in Lakewood, about 40 minutes from Oberlin. Griff Dye, a clinical psychologist, will continue to practice in Oberlin, and the couple intends to visit friends and take in concerts and art exhibitions at the College. She will also continue her work with several organizations: Search for Common Ground, a conflict resolution NGO based in Washington, D.C.; IREX (International Research and Exchanges Board), on whose board she sits; the United Negro College Fund’s Institute for Capacity Building; and, of course, Oberlin Shansi. In addition, she will do some work for the just-emerging Asian University for Women in Bangladesh.

Her ideal new job, however, would be to spend a year teaching American history at the University of Shiraz. “Griff and I became globalists while at Oberlin, particularly with respect to the Middle East and Asia,” says President Dye. “I had never been to Asia when I arrived in Oberlin. In fact I had never been any place that was not part of the North Atlantic community. Going to Japan and China and Hong Kong in the summer of 1995 was just a revelation to me.

“A few years later, the College granted me a sabbatical, and Griff and I spent most of the semester in Asia, visiting all of the Shansi sites and other parts of Indonesia, Japan, China, India, and Central Asia (known as the ’Stans) on our own.”

That sabbatical sparked the president’s interest in public and cultural diplomacy. She has since traveled to Jordan and Iran under the auspices of Search for Common Ground and is continuing to lead Oberlin’s efforts to work to create a musical exchange with the University of Tehran’s music school.

At Oberlin, the results of her work in the international arena are evident.

“I think we have probably the strongest undergraduate East Asian studies program of any institution and, within that, the strongest Japanese and Chinese studies programs. These are very important for the future of Oberlin,” she says, noting that the College also puts strong emphasis on Asian history, religion, and art.

She wants Oberlin to recruit more international students. “I think we need more international students, which is not easy to bring about,” she says. “International students are expensive, and

Oberlin has always welcomed international students in significant numbers and has aided those students well. We need to build on that legacy. We already are unusually cosmopolitan, but we could really improve on that. We have students now from more than 50 nations, and we could have many more students who come from Asia, Africa, Europe, and Latin America.

To that end, President Dye and her husband made a two-week student recruitment trip to Pakistan last fall. “Of all the schools in Karachi and where we visited, we were told that this was the first year since September 11, 2001, that any American college or university had returned to recruit their students. In fact, only four American institutions—Harvard, Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, and Oberlin—visited Pakistan at all this year,” she says. “Oberlin will have four students from Pakistan in its freshman class next fall.”

A Lasting Legacy

Nancy Dye has made countless contributions to Oberlin College during her 13-year tenure as president, but these are among the most important. “All of these were achieved in concert with faculty members, the administration, the Board of Trustees, alumni, and students,” President Dye says emphatically.

- Dramatically improving Oberlin’s admissions numbers in both the College and the Conservatory, particularly in terms of selectivity, academic achievement (grades, SATs, class rank), and yield.

- Improving financial aid policies and funding to the point where Oberlin could meet the full financial need of each student in the College and the Conservatory and could provide significantly more merit scholarships, especially in the Conservatory.

- Leading and successfully concluding Oberlin’s recent capital campaign by raising $175 million—$10 million over the goal.

- Bringing to fruition a new strategic and financial plan.

- Building a new Science Center, “which is without question one of the best facilities anywhere for teaching and learning science,” President Dye says.

- Approving and supporting construction of the Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies.

- Restoring both the exterior and interior of the Allen Memorial Art Museum, a distinguished hallmark of Oberlin architecture.

- Initiating and gaining support for saving Oberlin’s Allen Memorial Hospital.

- Creating the Oberlin College/School Partnership, the Oberlin High School Scholarship program, and a new master’s degree program in teacher education.

- Creating the Center for Service and Learning, which gives Oberlin students rich and meaningful opportunities for civic engagement in northeast Ohio while providing genuinely helpful service to local organizations and schools.

- Establishing a strong and very diverse Dean of Students’ office that is exceptionally well-positioned to support all Oberlin students.

- Establishing an Office of the Ombudsperson, which in turn has established a model student mediation program and the Oberlin College Dialogue Center.

- Making Oberlin more student-centered by establishing the Dean of Studies office to coordinate and improve student advising programs and to lead efforts to improve student retention to graduation.

- Significantly improving Oberlin’s athletics program.

- Becoming the first president of an American college to establish an ongoing relationship with Iranian higher education.

Civic Engagement

As her days in office wind down, President Dye finds herself the subject of much flattering praise. One such instance occurred during a dinner to celebrate the College’s Bonner Scholars and to announce a $4.5 million grant from the Bonner Foundation to endow Oberlin’s program. President Dye was praised for starting Oberlin’s Center for Service and Learning and for supporting the Bonner Scholar program, which was struggling to survive at Oberlin when she arrived.

Bonner Foundation President Wayne Meisel elicited a standing ovation for President Dye when he said, “Every time I’ve had an idea, every time I’ve had a struggle or a question, she has been the most supportive, the most attuned, the best listener of all the college presidents that I’ve ever worked with. She has been in many ways the silent hero who brought us here today.”

Daniel Gardner, whom President Dye recruited to lead the Center for Service and Learning, which she created in the first months of her presidency, says he really had no intention of taking the job when he came in for the interview. He was at the time traveling the country talking to college and university presidents about campus/community partnerships.

“I can admit now that I took the interview in no small part as a way to catch up with some old friends in Oberlin, but Nancy’s understanding of civic engagement, both intellectually and practically, exceeded that of any of the scores of presidents I had met in my work,” says Gardner. “Nancy understood that civic engagement was not an afterthought of the college experience, but central to an Oberlin education.”

Concrete examples of the College’s civic engagement are evident.

“The city and the schools have benefited from Nancy’s acknowledgment that the town’s and the College’s fates are intertwined. Were it not for her, we would not have a hospital in this town, and residents would be entering their 67th year of talking about constructing a community pool,” says Gardner. Community service is now infused in every aspect of the College; Gardner says it will be President Dye’s lasting legacy.

“Surely this thorough institutionalization of civic engagement will be felt generations from now,” says Gardner. “Nancy’s vision of service as a fulfillment of higher education’s civic mission seems permanently embedded within Oberlin College.”

The late William Perlik ’48, former Board of Trustees chair and a source of inspiration for President Dye, said in 2001, “If I have ever done anything good for Oberlin College, it was whatever role I played in getting her here.”

Portrait of a Leader

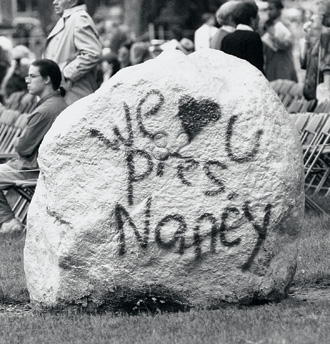

At the unveiling of her presidential portrait in March, Wendell P. Russell ’71, president of the Alumni Association, spoke of President Dye’s legacy.

“Years from now, when your alumni friends who knew you and worked with you stand before the portrait that we unveil this evening, they will smile and say, ‘She was one of the great ones. And those were good years for Oberlin.’”

Dean of Students Linda Gates marveled during the portrait unveiling at “the energy, determination, and seriousness of purpose that Nancy brings to any endeavor, and her lively sense of humor and good cheer, even when the work is hard and there are bumps in the road.”

At the same event, David Kamitsuka, professor of religion, considered the Board of Trustee’s search for a successor and the list of desired presidential attributes:

...creativity, idealism, breadth of curiosity, social and civic engagement, personal characteristics of warmth, a sense of humor, consistent expectations for excellence in people and programs … A visionary leader … A person who can appreciate the history, culture, and values of Oberlin … A strategic and accomplished thinker who will lead by ideas … A person of global perspective, committed to diversity …

“The [qualities] of Oberlin’s sought-after 14th president have an uncanny resemblance to Oberlin’s 13th president,” Kamitsuka remarked. “I can think of no higher compliment for President Dye than this.

“In the years to come, when I look at the portrait of Oberlin’s first woman president, I may indulge myself with a moment of nostalgia, but I will also remember Nancy’s call for all of us to think fearlessly and creatively about Oberlin’s future.” l

Mike McIntrye is a writer and columnist for the Plain Dealer in Cleveland.