Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Spring 2007 Vol. 102 No. 4

Redemption in Words

Ishmael Beah ’04 is the author of A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, published in February by Sarah Crichton Books, an imprint of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. He lives in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Ishmael Beah ’04 is the author of A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, published in February by Sarah Crichton Books, an imprint of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. He lives in Brooklyn, N.Y.

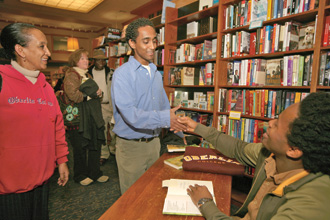

About two dozen Obies attended Beah’s Cleveland-area book signing in March. The book has been lauded by critics for its literary achievement and social significance. In his review for the New York Times, William Boyd wrote that A Long Way Gone is “perhaps the first time that a child soldier has been able to give a literary voice to one of the most distressing phenomena of the late 20th century: the rise of pubescent (or even prepubescent) warrior-kiler.”

About two dozen Obies attended Beah’s Cleveland-area book signing in March. The book has been lauded by critics for its literary achievement and social significance. In his review for the New York Times, William Boyd wrote that A Long Way Gone is “perhaps the first time that a child soldier has been able to give a literary voice to one of the most distressing phenomena of the late 20th century: the rise of pubescent (or even prepubescent) warrior-kiler.”

New York City, 1998—

My high school friends have begun to suspect I haven’t told them the full story of my life.

“Why did you leave Sierra Leone?”

“Because there is a war.”

“You mean, you saw people running around with guns and shooting each other?”

“Yes, all the time.”

“Cool.”

I smile a little.

“You should tell us about it sometime.”

“Yes, sometime.”

Ishmael Beah ’04 is in Cleveland this March evening, reading a passage from his new book to 75 listeners cramming the entrance of an upscale bookstore. With a sparkling, infectious grin, he easily charms his attentive audience; many of them have braved a rush-hour commute from Oberlin to meet a favorite son.

The question-and-answer period yields more adulation than inquiry. In the past weeks Beah has appeared on the Daily Show with John Stewart, CNN, and virtually every morning news show in America; in the coming week, his book will top the New York Times and Washington Post nonfiction bestseller lists. This particular Thursday also brought him local radio and television interviews and yet another appearance at Starbucks; the chain is selling his book as part of a special promotion that requires his presence at multiple stops along a 15-city tour. At age 26, Beah is becoming a star, a big one. Some might even say venti.

It’s a grueling schedule for a young man who had graduated from college just three years earlier. But considering where Beah’s journey started—5,000 miles away in a village in Sierra Leone—and the emotional ground he has since covered, the demands of a book tour seem trivial.

Beah was 12 when the Sierra Leone civil war moved into his small village on the southwest coast. The war seemed to pursue him as he fled, sometimes alone, sometimes in a pack of other similarly burdened young boys, through dense forests and narrow trails, through hunger and fear, through the loneliness of being apart from his parents and brothers, and through the grief of finding that they’d been killed. When the war finally caught up with Beah, it nearly devoured him.

By the time he was 13, he’d been taken in by the Sierra Leone army, which fueled him with cocaine, marijuana, Rambo movies, and a taste for vengeance that turned him into a child soldier, capable of truly terrible acts. When rescued by UNICEF workers two years later, he and his fellow young soldiers, fighters from both sides of the war who had little understanding of what it was about, violently resisted any attempts at rehabilitation. They were soldiers:

[1996]—As soon as the live-in staff, mostly men, started telling us what to do, we would throw bowls, spoons, food, and benches at them. We would chase them out of the dining hall and beat them. During that same week, the drugs were wearing off. I craved cocaine and marijuana so badly that I would roll a plain sheet of paper and smoke it. We [the boys] would fight for hours for no reason at all.

Rehabilitation was painful and confusing. Eventually Beah was united with an uncle who was supportive and kind, and he began a new life in the capital city of Freetown. The identity he had clung to as a young teenager was slowly fading.

“I never spoke about my personal background in high school or at Oberlin,” he says. “A few people, a few friends over time found out—I guess because they stumbled upon certain things,” —mainly, he explains, evidence of his speaking engagements as a human rights advocate in high school.

“I always could tell when somebody found out about my past. They would say, ‘Soooo, Ishmael…,’ and I knew.”

When his adoptive mother—a white Jewish-American woman from New York—visited Beah at Oberlin, fellow students would ask if he was adopted, or if his mom had met his father in Africa. “People had different assumptions, but no one could imagine what had really happened.”

Still, it was not the judgment of his peers, so much, that kept him from sharing his childhood story.

“I didn’t think that as a first introduction—‘Hi, my name is Ishmael, I used to be a child soldier’—would do any good,” he explains. “There’s more to me than that. When people get to know me, they will learn about my past. I don’t think I cared whether or not anyone judged me. I know what happened to me, and why.”

Not until a January 2007 cover story appeared in the New York Times Magazine did Beah’s Oberlin acquaintances realize the full extent of the war’s impact on his life. His is a harrowing, yet riveting tale of survival. It is also his attempt to explain the context, to bring readers, as he says, “to that landscape” where they can understand why people did what they did.

[1994]—That evening we learned how to fire our guns, aiming at plywood boards mounted in the branches of tiny trees at the edge of the forest. … That night, even though I was exhausted, I couldn’t sleep. My ears rang with the gun sounds, my body ached, and my index finger was sore. I imagined capturing several rebels at once, locking them inside a house, sprinkling gasoline on it, and tossing a match. We watch it burn and I laugh.

Leaving the Past

In 1996, while living with his uncle’s family, Beah was invited to New York to speak at a United Nations conference about the effects of war on children. It was his first venture out of Sierra Leone, his first time on an airplane, and his first experience with snow. At the conference he met and befriended Laura Simms, who identified herself as a storyteller—a role that fascinated Beah, steeped as he was in his own African storytelling traditions. The trip, he would later write, was like a dream. “If I was to get killed upon my return [home], I knew that a memory of my existence was alive somewhere in the world.”

By the following year, the war had reached Freetown. Beah’s uncle had fallen sick and died, so Beah, fearful of being forced to rejoin the army, made a collect call to Simms in New York. Could he come stay with her if he was able to make it out of Sierra Leone? Yes, she said. He left a few days later. It was another difficult journey, dodging machine-gun fire, evading checkpoints, lying motionless in gutters for hours, and traveling in the dark after curfew. He eventually made his way to neighboring Guinea and, some months later, to New York, where, adopted by Simms, he enrolled in the U.N.’s International School and lectured around the country.

It was at one of these speeches, at the State of the World Forum in San Francisco, that Beah’s journey first pointed toward Oberlin.

“There was an Oberlin graduate there—I don’t remember his name—who spoke about human rights and the need for them to override the use of power in government. He spoke so eloquently and so well, that afterwards I spoke to him. I said I was in 12th grade and looking at colleges. He said, ‘There’s this school I went to, Oberlin. I think you might like it, maybe you should check it out.’ So I went back and told my counselor. She said, ‘Actually, I too was thinking that you should look at that school.’”

Beah visited Oberlin that spring (“when it’s quite beautiful—that’s why they have you come in the spring,” he laughs), where he sat in on a political science class and met other African students.

“I loved the ambiance—the class, the way students were interacting with the professor and what they were saying. ‘This is a cool place,’ I thought. ‘It seems everyone is interested and passionate about different things.’” In the fall of 2000, Beah entered Oberlin and became a political science major.

“I was scared when I got to school. In Sierra Leone, most people my age at the time—even now—did not have access to a college education. They don’t have the money, and the opportunity is not there. So I took school very, very seriously from the get-go.”

Despite his love for words—Beah read Shakespeare as a child, embraced the storytelling culture in which he grew up, and thumbed through the dictionary to understand American hip-hop lyrics—he was apprehensive about his own writing. To shore up his skills, he enrolled in a rhetoric and composition class at Oberlin, where he found students who shared his insecurity about their writing ability. He also found Laurie McMillin, associate professor and chair of the rhetoric and composition department.

In an early course assignment, McMillin asked students to set out onto campus and simply write what they observed. Beah compared the innate sounds of nature with the reticence he observed among freshmen in a dining hall.

“He was very attentive to birds and trees and what was going on around him,” says McMillin. “What impressed me was the way he contrasted the fear and silence of his classmates with the interaction and communication outside the College buildings.”

For another assignment, McMillin asked students to write about a childhood play area. Beah, unlike his classmates, faced a difficult decision.

“I thought, ‘Well I played quite differently at different times in my life. There was a time when I played the way other kids played, but there was also a time when I played in a more deadly way,’” says Beah. “But I didn’t want to write that; I didn’t want other people to know.” Instead, he described in great detail how as a young child he and his friends would make and play with a small toy called a gigee.

Starbucks and the Oberlin “Stuff”

Starbucks had one just question for Ishmael Beah when they asked to sell his book in their 6,500 coffee shops.

“How do you feel if Starbucks recommends your book to its customers? Is this going to clash with your Oberlin…stuff?,” Beah recalls, laughing; “stuff,” of course, referring to Oberlin’s comfort level—or rather discomfort level—with giant corporations and the marketplace.

“I told them I needed to think about it for a while,” says Beah.

Starbucks, he was told, would simply buy the book and resell it; they were not asking for exclusive rights. The company pledged to donate $2 per sold book to UNICEF projects related to children and war, with a minimum contribution of $100,000. (The book sold at least 100,000 copies during the promotion, according to the company.)

“I wanted a lot of people to read this book,” Beah says. “And these guys were going to help me reach a demographic that I wouldn’t be able to reach in traditional bookstores. So I told them to go for it.”

Dan Chaon, too, has no problem with the book’s placement at the coffee shop counter.

“The fact is, the issue of child soldiers is an important story that’s not being covered by the mainstream media,” he says. “I don’t care if they sell Ish figurines at McDonald’s, as long as people are aware of this horrible tragedy.”

“Not only was it so different,” recalls McMillin, “but he wrote about it so well. The world—the time and place and situation and joy he conjured up was infectious.”

Beah, for his part, was surprised to find his classmates so intrigued by his story. “My entire class was very interested in the world I was from, one that was so far removed from their own. They wanted to understand. There were lots of questions.

“I began to realize: ‘You know what? People are interested in my past.’ It got me thinking that perhaps I really could write about the war, how I lived it, so that people could understand how it came about and affected people.”

Beah did a private reading with McMillin, and the pair later coauthored a dialogue about the creative relationship between students and teachers. “I once asked Ishmael how he managed to stay so light and bright, given all he had seen,” McMillin wrote. “It was an awkward moment, really, and I feared I had strayed too far. He replied that he had to focus on what was good in the world, that he didn’t see the value of dwelling on the past. I was weeping then. … But he continued, saying that writing had helped him understand his life, really helped him.”

In the piece, McMillin also predicted Beah’s success. “I know that Ishmael will publish a book, that we will hear of him in the New York Times Book Review,” she foreshadowed. “He is that good.”

Beah pursued his growing interest in writing, taking a creative fiction-writing workshop with novelist Dan Chaon, an associate professor of creative writing. In one assignment, Beah wrote a story about a dog that was so mad with hunger that he attempted to smash open a coconut for food:

After several tries, the dog started crying, its feet trembled and it lost its stamina. Unable to get up, it crawled into the gutter with the coconut where it laid and died. No one has ever seen such a thing. Dogs in their right mind and in the right circumstance do not try to break open coconuts. It was clear that things were getting worse.

“Dan quickly picked up that it wasn’t fiction,” says Beah.

Chaon knew a bit about Beah (or Ish, as Chaon calls him) and had a sense of the turmoil that had made up his childhood. That knowledge allowed Beah to open up more. “You have talent,” Beah remembers his professor saying. “You just need to work on a few things. Continue writing, and if you want to write this story, I will help you.”

Beah enrolled in Chaon’s nonfiction workshop and soon began churning out 10 to 40 pages per week. “There are a lot of stories in this one short story,” Chaon told him. “Think you can make it focus on one thing?”

Chaon led Beah to books written by Chris Adrian, Raymond Carver, and Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah for examples of “getting detail and scene down in a concise way. Ish knows how to tell a story,” says Chaon. “He would write these amazing descriptions in that early work. It felt like there was stuff struggling to get out.”

“I learned early on that Dan was very aware that this was the kind of story that people could sensationalize quickly. He said that I needed a vision,” Beah says. “I needed to follow that vision and not sway from it at all, regardless of what the outcome might be.”

Once or twice a week, Beah would consult with Chaon, sometimes discussing the work line by line. He began writing his book in earnest the second semester of his junior year.

“I was shocked by the material,” admits Chaon. “It was strange for me; I didn’t know how bad things were going to get. As I was reading, I didn’t realize how many people were going to die. I didn’t realize that his family was going to die. I didn’t realize how deeply involved in the war he was.

“Working as closely with someone as [we were], seeing them every week, walking with them through loss of home, loss of family—you get intensely close to them,” says Chaon. “But it wasn’t my job to get upset by this stuff. He’s the person who had this experience and the experience of reliving it and writing it down. I felt great admiration and respect for him, so I made the decision to simply be the best writing teacher I could be.”

It wasn’t always easy. “I still think about moments where I’d say things like, ‘The scene where the kid dies needs to be more vivid.’ There’s something monstrous about that. But he got closer and closer to his emotional truths.”

Early on, Beah says, Chaon encouraged him to be “painstakingly honest,” to the point where he could vividly recount the exhilaration of his past violence. “If I ever tried to veer away from being frank and honest, it would disturb me. I knew I’d be doing a disservice to the people who were there, and to myself as well.”

Beah’s final semester at Oberlin was not as leisured as some of his graduating classmates’. He was working frantically to finish his book and maximize his time with Chaon. The final manuscript came in at close to 400 pages.

After Beah’s graduation, Chaon continued to offer feedback and editing help via e-mail. “To this day I have Dan’s cell phone number and call anytime,” says Beah. “You don’t create this kind of relationship with professors at other schools.”

A list of Oberlin professors appears in the acknowledgement section of Beah’s book. It was they, he says, who helped him find the right words. l

Jeff Hagan is a freelance writer in Cleveland.