Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Spring 2008 Vol. 103 No. 3

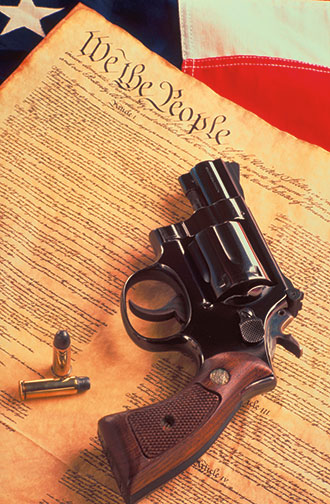

Taking the Second Amendment to Court

Dennis Henigan ’73, vice president for law and policy at the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence

Dennis Henigan ’73, vice president for law and policy at the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence

When the Supreme Court decides its potentially most significant gun control case in 70 years this spring, Oberlinians will have played a major part in laying the groundwork.

It was back in the 1930s when the high court last issued a full opinion interpreting the Constitution’s Second Amendment on the right to bear arms. The dispute that has led the justices back into the legal thicket of gun control started in 1976, when Washington, D.C., enacted one of the nation’s most stringent gun laws, a statute that essentially bans city residents from acquiring handguns.

Three decades later, the Supreme Court is considering a challenge to the measure. Last year, a federal appeals court unexpectedly found D.C.’s law in violation of the Second Amendment, which states: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

When the capital’s law went on the books, Dennis Henigan ’73 was attending law school and Adrian Fenty ’92 was in elementary school. Both would play key roles when it came time for the issue to gain national prominence. When the appeals court ruled last March, Fenty had just become mayor of D.C. and Henigan was director of the Legal Action Project at the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence, which has litigated many of the gun-control movement’s major cases.

Fenty, a lawyer whose rise to power was chronicled in the winter 2007 issue of this magazine, inherited a case that had been filed against the city before he took office. Timing dictated that it was his job to make the decision on whether to take the case to the high court. His move to seek review by the Supreme Court was not universally hailed by gun-control advocates, who fear that it could lead to a major setback for their movement nationwide.

It might not be surprising that Henigan holds an important public-interest law position—a field widely populated with Oberlin alums. What isn’t so obvious is how Henigan, who lacks a lifelong history of activism on gun issues, became a major player in the movement and has stuck with it for nearly two decades.

It started with an interest in debating. Henigan grew up in northern Virginia, where his father was the debate team coach at nearby George Washington University. Like college football teams that seek out local high school stars, Oberlin, which Henigan says had a “powerhouse college debating program” in the 1960s, spotted Henigan. Then-Oberlin debate coach Daniel Rohrer knew Henigan’s father, and Oberlin debaters like Roger Conner ’69 and Mark Arnold ’70, encouraged Henigan to enroll in the College. He was quickly persuaded, and ended up winning debate tournaments as part of a team with Arnold.

The early 1970s was a time of anti-Vietnam War activism on campus. Henigan became caught up in activities opposing the war and gradually left debating. He became fascinated with the study of philosophy, working with Professor Norman Care and graduating with high honors. To earn that designation, he was required to defend a thesis before three faculty members as if it were a PhD project. “Oberlin taught me how to think, to question my own conclusions constantly and never to be quite satisfied,” Henigan says. “No matter how well you think you’ve thought things through, a good professor will get you to go deeper.”

Henigan thought about continuing his philosophy studies in graduate school, but instead decided to take up law at the University of Virginia, traditionally one of the top U.S. law schools and a much more conservative institution than Oberlin. After graduation, he landed a position in the D.C., office of the national firm Foley & Lardner. One attraction for Henigan was the firm’s commitment to public-interest law. He became involved in housing work and helped create the Fair Housing Council of Greater Washington, which sent white and black testers to the same places to determine if their policies were discriminatory.

In general, Henigan believed that “the law could be a powerful tool for a progressive society, to attack problems of the less powerful.” In his 11 years at Foley & Lardner, where he became a partner, Henigan lived the two professional lives pursued by many lawyers: doing primarily corporate work, but spending substantial time on public-interest matters. Ultimately, he observed, it “seemed like the public-interest lawyers were having a lot more fun,” and so he sought out full-time opportunities in that field.

Unbeknownst to Henigan, in the late 1980s an organization called Handgun Control, Inc., one of the leading national gun-control advocacy groups, had decided to start a legal arm. Henigan had been sympathetic to the cause but never active in it. He answered the group’s ad in a legal publication and was hired.

The Washington, D.C., Gun Law

June 1976: The D.C. Council, in an effort to curb gun violence, passes a gun-control law that restricts city residents from owning handguns. The law exempts police officers, guards, and gun owners who had registered their handguns before it took effect. Rifles and shotguns, which are not restricted by the law, must be kept unloaded, disassembled, or locked except those in business establishments.

February 2003: Six D.C. residents sue the city, arguing that the gun ban violates their Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms.

March 2004: U.S. District Judge Emmet G. Sullivan dismisses the suit, ruling that the Second Amendment was tailored to membership in a militia, not to individuals.

March 2007: In a 2-1 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit overturns Sullivan’s decision, ruling that while the District can regulate firearms, it cannot prevent people from owning handguns.

May 2007: The full federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., lets the March ruling stand, paving the way for a possible Second Amendment showdown in the Supreme Court. Mayor Fenty must decide whether to bring the case to the high court or to revise D.C.’s handgun laws.

September 2007: Mayor Fenty asks the Supreme Court to uphold the gun ban.

November 2007: The Supreme Court agrees to take the case, now known as District of Columbia v. Heller, weighing the constitutionality of the 31-year ban on handguns. The Supreme Court hasn’t ruled on the Second Amendment in nearly 70 years.

March 18, 2008: The Supreme Court scheduled to hear arguments, with a decision expected by summer recess.

– Source: The Washington Post

At the time, some personal-injury lawyers had gone after gun makers the same way they had successfully sued the tobacco industry. Their problem was that unlike cigarettes, which are arguably defective products because of their hidden danger to health, guns are intended to be dangerous. It was difficult for critics to win judicial opinions or jury verdicts holding companies liable for damages.

Henigan viewed the long list of unsuccessful lawsuits as a challenge. “It was a fascinating opportunity to make new law,” he recalls. “I didn’t allow myself to be discouraged.” He viewed the task as comparable to inventing the civil-rights and environmental-law movements: “It was an undefined idea. I wanted to help create legal theories to hold accountable those who were increasing the risk of violence.” In one breakthrough case in 1986, a Maryland court did hold liable a maker of the cheap handgun known as a “Saturday Night Special.” The National Rifle Association worked hard to defeat a state referendum to ban the guns, but it passed anyway. Henigan called the result a turning point in the battle for public support on gun control.

On a federal level, gun-control forces were at a low point during the Republican-dominated 1980s, but things changed dramatically during the administration of President Clinton, whom Henigan calls “the most effective gun control advocate I’ve ever encountered.” In Clinton’s early years came enactment of a federal law prohibiting manufacture of many assault-style weapons, as well as the Brady Law, which required background checks on gun buyers at gun stores. The law was named for former White House press secretary Jim Brady and his wife, Sarah, who was board chair of Handgun Control. In honor of the Bradys, the group renamed itself the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

For his part, Henigan started as a one-man “legal action project” that helped recruit law firms to defend state and local gun-control laws from attack by gun-rights advocates. On the liability front, he abandoned the argument that guns were inherently defective products and instead moved to a “third-party liability” theory to hold companies accountable when their irresponsible conduct enabled dangerous individuals to get guns.

The first major victory came in a 1999 California appeals court ruling that the maker of a semiautomatic pistol known as the TEC-9 could be held liable for a 1993 shooting in which a man entered a San Francisco law firm and killed eight people and himself. Similar cases were later filed on behalf of cities with high crime rates. The litigation’s high-water mark was in 2004, when a total of more than $4 million in damages was paid to victims. That included a $2.5 million settlement in a case brought by victims of the snipers who terrorized the Washington, D.C., area in 2002. The cases were something of a victim of their own success. Gun advocates, with support from the White House, finally were able to counter the lawsuits when Congress enacted a hotly disputed 2005 federal law limiting the gun industry’s liability.

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing on the Second Amendment front. When Henigan joined the movement, there seemed no doubt that the Second Amendment did not block gun-control laws. Gun-control advocates argued that constitutional provision referred to the long-abandoned idea of citizen militias. Still, libertarians and some conservatives kept pushing the theory that modern laws that kept guns out of law-abiding citizens’ hands were inconsistent with the amendment.

Finally, they succeeded in persuading a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to rule 2-to-1 in March 2007 that the D.C. law ran afoul of the Constitution. Judge Laurence Silberman said the amendment was not intended to apply only to militia members. “The Bill of Rights was almost entirely a declaration of individual rights, and the Second Amendment’s inclusion therein strongly indicates that it, too, was intended to protect personal liberty,” he said.

Because nine other federal appellate courts had ruled the other way, the outcome came as something of a surprise to Henigan and most other legal experts. The ruling posed a dilemma: If Washington, D.C., did not pursue it further, the city would lose a key gun-control law but the ruling would not affect other gun-control measures in states and localities around the nation. Ultimately, Fenty decided to move forward: “Having a handgun, whether in the home or outside it, comes at the expense of those who might be victims,” read the city’s petition to the court. “Whatever right the Second Amendment guarantees, it does not require the District to stand by while its citizens die.”

Henigan consulted with the District’s legal advisers throughout the case but had not actually met the mayor until a press conference was held the day of the D.C. Circuit’s ruling. Introducing himself as a fellow Oberlin alum, Henigan says, “It was a nice Oberlin moment for me.”

In November, the high court announced that it would hear the case this spring. At issue in District of Columbia v. Dick Anthony Heller is whether provisions of the city’s law “violate the Second Amendment rights of individuals who are not affiliated with any state-regulated militia, but who want to keep handguns and other firearms for private use in their homes.”

In January, Henigan’s group filed an amicus brief at the Supreme Court supporting the District’s appeal. He represented nine other groups in addition to his own, including the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives.

In the brief, Henigan and fellow attorneys argue that the “lower court’s insurrectionist view of the militia and the Second Amendment has disturbing implications for public safety and the rule of law.” Citing paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the Oklahoma City bombers, Henigan said that the D.C. Circuit ruling “may well limit the government’s power to punish political violence after the fact and surely would curb the government’s power to prevent the stockpiling of weapons….”

With the high court not having fully considered Second Amendment issues in such a long time, many legal analysts believe that the outcome of the case is too close to call. A definition of the Second Amendment as a broad right unrelated to militias could lead to a generation’s worth of legal challenges to other gun control laws. If Washington’s ban is upheld, the gun-control battle will move back primarily to the legislative front. At the Brady Center, Henigan, who was once alone in his work, now supervises 11 employees as vice president for law and policy, where he is in charge of legislative work and litigation.

Whatever happens in the Supreme Court case, Henigan’s reputation among his colleagues seems secure. Says Robert Walker, former president of Handgun Control: “More than just a great legal mind, Denny was a visionary. In setting up and directing the Legal Action Project, he saw its full potential. He is one of the greatest public interest lawyers of our time.”

Ted Gest, who covered the Supreme Court for U.S. News & World Report, now heads Criminal Justice Journalists, a national group affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania and John Jay College of Criminal Justice.