Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Spring 2011 Vol. 106 No. 2

Creating Old-Time Music for the

21st Century

To see Punch Brothers, you’d easily think they’re a pretty standard old-time folk band. The bandmates are well dressed in suits and ties and line up across the stage with the bass in the back and fiddle, mandolin, banjo, and guitar—played by Chris "Critter" Eldridge ’04—in front. But listen to Punch Brothers and you realize their sound is worlds away from standard folk or bluegrass. Their repertoire includes radically remade covers of songs by Fiona Apple, Radiohead, and what they introduce as "a rival old-time band from New York called The Strokes." Their original songs have elements of pop-friendly bluegrass, but with elaborate classical structures woven in.

Likewise, the Carolina Chocolate Drops, featuring Rhiannon Giddens ’00, come off as an old-time string band, but they’re hip enough to cover Tom Waits and Blu Cantrell accompanied by kazoo, human beatbox, and rip-roaring dance.

Although the conservatory doesn’t offer a bluegrass concentration, that hasn’t stopped Oberlin students, including many from the conservatory, from making it their own focus. Recent years have seen a thriving old-time folk scene develop—one that reverberates far beyond campus and far beyond the music’s traditional roots. Punch Brothers were nominated for two Grammy awards this year, and the Carolina Chocolate Drops won one for best traditional folk album. The Chocolate Drops’ major-label debut album, Genuine Negro Jig, even cracked the Billboard 200 chart. That’s a pretty incredible accomplishment for a group reviving the African-American stringband tradition that had its heyday during the Great Depression.

"It might seem counterintuitive to think that at Oberlin, which has a world-class jazz studies program and is the oldest [continuously operating] music conservatory in the country, many people would be interested in playing dulcimer, banjo, and fiddle," says Johnny Coleman, a professor of art and African-American studies who leads banjo-making workshops. "But they are. It’s pervasive."

Punch Brothers (from left to right): Noam Pikelny, Gabe Witcher, Paul Kowert, Chris Thile, and Chris Eldridge ’04. (photo by C. Taylor Crothers)

Punch Brothers (from left to right): Noam Pikelny, Gabe Witcher, Paul Kowert, Chris Thile, and Chris Eldridge ’04. (photo by C. Taylor Crothers)

Had all gone according to her original plan, Rhiannon Giddens would now be singing opera instead of old-time. Giddens says she turned down a full scholarship to Carnegie Mellon University because of its reputation for musical theater (she disliked talking on stage) and opted instead to study opera at Oberlin ("all singing and no talking").

By Giddens’ own admission, all she knew about opera was what she’d seen on television. So her decision took a lot of verve, and she got by on enthusiasm as the self-proclaimed "quintessential nerd."

"I was so excited to be doing music all the time, and no math or science," Giddens says. "I was in the classical bubble so much that I didn’t find out until afterward how much of a folk history Oberlin has. Josh Ritter was at Oberlin when I was, but I didn’t know it because I was really focused on the conservatory and other aspects of the business. I did publicity, the Oberlin opera website, worked the box office, ushered. The skills I learned really helped later."

Giddens’ voice teacher, Professor of Singing Marlene Rosen, says Giddens was "an open book" when she first came to Oberlin. But she thinks Giddens would have made her mark in the classical world had she stayed on that path.

Right: The Black River Belles (from left to right): Helena Thompson ’11, Erin Lobb ’11, and Sara Sasaki ’11. (photo by Ma’ayan Plaut ’10)

Right: The Black River Belles (from left to right): Helena Thompson ’11, Erin Lobb ’11, and Sara Sasaki ’11. (photo by Ma’ayan Plaut ’10)

"She hadn’t had much training when she first got here," says Rosen. "But there’s something very special and warm and exquisite about her voice. It has its own beauty, no matter the style. She was always interested in a lot of different things. So it came as no surprise when she went off in this other direction and was equally magnificent at it."

Giddens’ first steps toward folk were by accident. Misreading a flyer advertising a contra dancing event, she showed up expecting "country dancing" of the kind described in Jane Austen novels. Giddens was hooked, and though she had to give it up for opera rehearsals, she found comfort in contra, especially after graduating in 2000.

"It had been a really intense five years, and I was burned out," Giddens says. "I had great instruction, but I still wasn’t feeling positive about my voice. So I came home to North Carolina and started contra dancing again. I loved the banjo sounds I’d hear at the dances, so I learned to play. Got a second job to buy a banjo, singing opera arias at a Macaroni Grill. I quit as soon as I bought the banjo."

Interest in the African roots of banjo and old-time music led Giddens to the Black Banjo Gathering, a 2005 conference at Appalachian State University. That’s where she met Dom Flemons and Justin Robinson, the founding members of the Carolina Chocolate Drops. Robinson has since gone back to school full time, and mandolin and guitar player Hubby Jenkins and world-class beatboxer Adam Matta have joined the band.

With their abundant skill and the novelty of 20-something African Americans playing old-time music, the Chocolate Drops took off like a rocket. They’ve appeared on the big screen alongside Denzel Washington in 2007’s The Great Debaters and played the Grand Ole Opry, A Prairie Home Companion, and every notable folk festival in America. They hope to continue that upward trajectory with their next album, to be produced by the spiritual country-blues guitarist Buddy Miller sometime this year.

Meantime, Giddens still keeps a toe in the classical world and sings when and where she can. She has a gig scheduled for June with the North Carolina Symphony.

"I play banjo for a living and sing opera for fun," she says with a laugh. "It’s a weird world. My banjo pays for my health insurance. Who knew?"

Ed Helms ’96, Erin Lobb ’11, and Chris Eldridge ’04 jam on the porch of Tank co-op. (photo by Caitlin Roseum ’11)

Ed Helms ’96, Erin Lobb ’11, and Chris Eldridge ’04 jam on the porch of Tank co-op. (photo by Caitlin Roseum ’11)

Chris Eldridge grew up watching his father play banjo in The Seldom Scene and work as a mathematician; Eldridge went to college figuring he’d follow in the family businesses. He chose Oberlin as an academic environment where he could pursue both.

"It seemed like a realistic thing," Eldridge says. "And of course, I didn’t do anything my first two years except sit in my room and practice guitar. I was a horrible student, skipped class routinely. By the end of sophomore year, I hadn’t even taken a single math class. But I was working, doing my thing. It was obvious I should become a music major."

Studying bluegrass guitar at a conservatory without a bluegrass program involved some creativity. Eldridge turned his recital into a bluegrass concert and even talked the school into providing enough funding for him to bring in out-of-town musicians. He also struck up a unique working relationship with his guitar teacher, Bobby Ferrazza, chair of Oberlin’s jazz studies program and associate professor of jazz guitar.

"We had an understanding that we’d do what we could," Ferrazza says. "He had an open mind and so did I. So he’d ask about how things struck me theoretically, and I’d help him with technical aspects. He was already strong as a bluegrass guitar player, so there was not a lot I could show him in terms of that. But I could help him with the aspect of music that crosses over and does not have to do with genres."

Eldridge’s Oberlin work in jazz and classical studies stood him in good stead for Punch Brothers, a group he joined after co-founding the bluegrass band Infamous Stringdusters. In fact, it was the only reason he could handle "The Blind Leaving the Blind," a 40-minute classical-style suite that was centerpiece of the group’s 2008 debut album, Punch.

"It was this whole different thing from what I was used to, literally scored out on staff paper," Eldridge says. "I came from the oral folk tradition and going through the music program was difficult for me. Unlike most conservatory kids who start reading music as 5-year-olds, the first time I tried was when I was 19. It was like learning a new language. But the curriculum at Oberlin taught me to interact with music on an abstract level. Without that, I wouldn’t have known where to begin."

In 2009, Eldridge came back to campus to play an event with comic actor Ed Helms ’96 (The Office, The Hangover, the upcoming Cedar Rapids), who started the bluegrass group Weedkiller at Oberlin and still plays with members Jacob Tilove ’96 and Ian Riggs ’97 in a group called Lonesome Trio. Helms’ Oberlin appearance was a combination comedy show/bluegrass concert with Oberlin students past and present, including Tilove. But the best part of the evening was the after-party, an all-night jam session at Tank co-op.

"We stayed until 4 a.m., jamming on the front porch," Eldridge says. "There are a bunch of students playing the music there now, and it was so much fun. It was also a far cry from when I’d been there and felt like I was the only one on campus playing old-time music."

One of the students playing that night at Finney and Tank was Erin Lobb, who will graduate in May with a psychology degree. Lobb plays in two different student groups, Outhouse Troubadours and Black River Belles, which both grew out of jam sessions. During winter term this year she hosted a weekly pot luck dinner and jam session in Oberlin.

"It used to be more under the radar, but it seems like it’s grown a lot even just since I’ve been here," Lobb says of the Oberlin old-time scene. "There’s no official organization for any of it, mostly just jam sessions at people’s houses. And it seems like a lot more underclassmen come now, too."

Carolina Chocolate Drops (from left to right): Dom Flemons, Rhiannon Giddens ’00, and Justin Robinson (Robinson has since left the band). (photo by Julie Roberts)

Carolina Chocolate Drops (from left to right): Dom Flemons, Rhiannon Giddens ’00, and Justin Robinson (Robinson has since left the band). (photo by Julie Roberts)

Helena Thompson ’11 is one of Lobb’s bandmates in the Black River Belles, and, like Rhiannon Giddens, she came to Oberlin to study classical singing. But Thompson’s focus has shifted to ethnomusicology, studying the history of banjo music and its roots in West Africa. She and Giddens met and bonded at the Oberlin Folk Festival in 2009.

"We’re both women of color within the bluegrass/old-time scene, and it was interesting to get her perspective," Thompson says. "It’s dominated by white males, and some people think it’s kind of weird for black women to be onstage performing music generally regarded as ’white.’ But they come around. It’s important to show people there are more sides to bluegrass than what it seems to be."

Onstage and in the classroom, it seems like the next generation of old-time music at Oberlin is in good hands.

"There will be quite an alumni network when I get out," says Lobb. "Lots of cities to go and find Obies to jam with."

David Menconi is a music critic at the News & Observer in Raleigh, N.C.

Folkfest 2011: Eli’s Coming

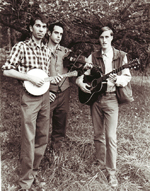

Dust Busters (from left to right):

Eli Smith ’05, Craig Judelman,

and Walker Shepard.

(photo by John Cohen)

One of the headliners at this year’s Oberlin Folk Festival on May 7 is the Dust Busters, an old-time string band led by Eli Smith ’05.

While they usually hew closely to tradition, the Brooklyn-based musicians are as downtown as they are down home: They spent three December nights opening for punk poet pioneer Patti Smith at the Bowery Ballroom, including New Year’s Eve. And that isn’t even their weirdest gig: Dust Busters did a tour of Bulgaria, sponsored by the U.S. State Department. The group has recently released the album Prohibition is a Failure, with John Cohen, a founder of the legendary band the New Lost City Ramblers.

Eli Smith hosts the online Down Home Radio Show, which showcases a wide range of bluegrass, old-time, and other traditional music, including Joe Hickerson and the Carolina Chocolate Drops. Its website is a rich resource that, among other things, keeps up with the members of Jug Free America, a band Smith co-founded while at Oberlin in 2001 (downhomeradioshow.com).

—Jeff Hagan ’86

Not Just Folks

Duke Ellington didn’t like dividing music into categories, believing there were only two types of music: "good music and the other kind." While all of the music discussed here falls into the first category, it’s hard to resist the urge to further classify the old-time-rooted music of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, Punch Brothers, and the on-campus musicians of Black River Belles and Outhouse Troubadours.

"The most obvious thing they have in common is that they started out from a similar place—from old time, with classical as a wild-card influence—even if they take it to quite different places," says the writer of this article, David Menconi, who is in his 20th year as a music critic at the News & Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina. "I also find it interesting that both the Chocolate Drops and Punch Brothers do covers of contemporary songs done up old-timey, which hints at a similar aesthetic approach."

Many of the musicians discussed here are also at home within the enduring folk music tradition at Oberlin.

The Folk Music Club (FMC) dates back to the mid-1950s when folk music artist Joe Hickerson ’57 was its president, according to Tom Reid ’80, manager of the Cat in the Cream coffeehouse and faculty advisor to the club. Hickerson was a founding member of the Folksmiths, eight Oberlin students who formed in 1956, took their Traveling Folk Workshop on the road during summer 1957, and released the album We’ve Got Some Singing to Do (Folkways Records) the following year. FMC’s current incarnation was formed by Josh Ritter ’99 and Ellen Stanley ’01 in 1999.

The club organizes the annual Oberlin Folk Festival, featuring student and local performers along with one or more touring headliners, some of whom—such as the Carolina Chocolate Drops—have included alumni. The festival is in its 13th year.

In 2004, members of the reconstituted folk club joined members of its earlier versions for a folk alumni conference in Oberlin (see OAM Spring 2005). "One of the cool things to emerge from that was the beginnings of building an archive of Oberlin folk music performances from across the decades," says Reid. "That work is continuing."

For more information on all things folk at Oberlin, including related events such as the Dandelion Romp dance festival, visit the Folk Music Club’s website: www.oberlin.edu/stuorg/folkmusi. Look for a profile of Josh Ritter in the next issue of the Oberlin Alumni Magazine. And join Joe Hickerson at his class reunion in May, where he plans to gather early folk music recollections, especially about the two Pete Seeger concerts held in 1954 and ’55. "And, oh lord," he adds, "we’ve got some singing to do."

— J.H.