Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Spring 2011 Vol. 106 No. 2

Oberlin

Beyond Oberlin

Making Moves into Movies

Bret Parker’s animation gig at Pixar still leaves room for performance work—including voicing the babysitter Kari in The Incredibles. Parker originally voiced the temporary "scratch" dialogue, but after auditioning actual teenagers, the director decided to keep her. (Courtesy of Pixar Animation Studios)

Bret Parker’s animation gig at Pixar still leaves room for performance work—including voicing the babysitter Kari in The Incredibles. Parker originally voiced the temporary "scratch" dialogue, but after auditioning actual teenagers, the director decided to keep her. (Courtesy of Pixar Animation Studios)

One Oberlin alumna has literally had her hand in nearly every major Pixar film, from Ratatouille and Wall-E to Finding Nemo and Monster’s Inc. Bret Parker ’91 has been using her experience in dance and theater to animate curious clown fish and gastronomically inclined rats since Pixar was a mere 200-employee studio.

Today, Parker works for Pixar and is an associate professor of animation at California College for the Arts, where she trains budding computer and art students in the basics of computer animation.

Funny thing is, Parker herself skipped animation school entirely, opting for a more creative approach to the art. Growing up in Maryland, she came to Oberlin to study English and dance performance, spending most of her time on campus in the dance studio. After completing her double major, she traveled to the Netherlands, where she attended grad school for performance. When she ended up in California, Parker started working as a temporary production assistant for Pixar on a whim, and slowly began to notice the connections between her performing arts background and animation.

"Animation made sense to me, with a background in dance and performance and theater," she explains. "It requires acting and choreography and timing." Parker eventually put together a reel and was hired on as the first fix animator for Pixar, beginning her work on A Bug’s Life.

Today, Parker is a full-time animator whose daily task is to bring characters to life. She and her coworkers act out the motions of Ratatouille’s mouse, Remy, scurrying through the streets of Paris, or of Wall-E picking up piles of garbage, and film themselves to watch the physics and movements of the motion. Then, the animators slowly and painstakingly recreate the action in single drawings, focusing on every detail, from a tail twitch to an eye blink. It’s not about copying, however, but caricaturing— using the video as reference to build upon as they animate.

"They say an animator animates about a second and a half a week," Parker says. Such close observation of movement, she adds, has found its way back into her performing life, as she has begun to focus on specific poses more in her stage work.

Though she is not at liberty to disclose what new project she is working on for Pixar today, Parker will definitely have imbued a bit of her dance and performance into the next talking car or silent robot to cross our movie screens.

Toward Better Fiction Science

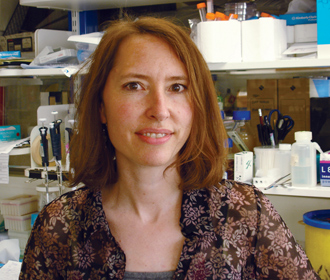

Courtesy of Jennifer Rohn

Courtesy of Jennifer Rohn

The Oberlin reputation for rooting out and fighting stereotypes, even in the most unexpected places, is alive and well with alumna Jennifer Rohn ’90. Rohn is using her background in molecular biology to smash scientist stereotypes and celebrate accurate laboratory-centered literature on her website, lablit.com.

In the past 10 years, Rohn has become a scientist advocate of sorts, on a mission to convince the culture critics that her co-lab workers listen to terrible techno pop, eat take-out pizza, and sleep with each other, just like everybody else. "[Scientists] are usually cast as troublemakers and hardly ever get to be true Hollywood heroes," she said in a BBC news interview.

Growing up in Stow, Ohio, an hour east of Oberlin, Rohn applied to Oberlin after reading a story in a 1983 Seventeen magazine written by a reporter who went undercover for two weeks of freshman orientation. "The headline was something like ’People who are geeks will be cool at Oberlin,’" Rohn recalls. "And I thought, that’s the place for me."

Rohn spent her four years at Oberlin in the science lab, majoring in biology, but found time to fit in various English classes as well. Her dual interests eventually led her to search for well-written fiction about scientists, of which she discovered a glaring lack.

In 2005, Rohn coined the term lab-lit and launched a website to go with it, discussing the portrayal of scientists, laboratories, and the scientific community in contemporary American culture. Her website is filled with short stories, essays, cartoons, and even music reviews—all centered around the idea of science as a legitimate and worthy subject for the humanities.

Today, Rohn continues to run her website from London and has published two lab-lit novels herself, The Experimental Heart in 2008 and The Honest Look in 2010, both of them from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. "It’s very difficult to get these books published, because the literary world is very anti-science," she explains.

Monica Klein ’11 and Jeff Hagan ’86 contributed to Oberlin Beyond Oberlin. Icon illustrations by Kristina Deckert.

Let Us Know: Where do you live,

and why?

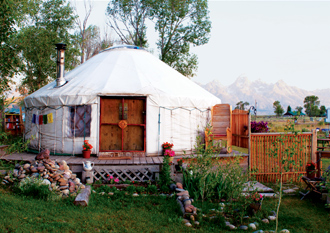

Grace Hammond lives in a yurt in a yurt park in Wyoming.

Grace Hammond lives in a yurt in a yurt park in Wyoming.

School librarian Grace Hammond ’04 lives in the Kelly Yurt Park in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, with her fiance, David Fanelli, a special education teacher. The village of Kelly, Wyoming, (part of Jackson Hole) is an inholding in Grand Teton National Park, with a population of about 200.

The yurt was, in the truest sense, an impulse buy. Upon the point of purchase, I thought of it as a round cabin with no running water rather than a gussied-up tent. As it turns out, it is the latter. At that time, I wouldn’t have bought it if I really understood it, and so I am glad I didn’t. It was something I had to grow into, and grow I did.

Courtesy of Grace Hammond

When I went to look at the yurt the first time, I was struck immediately by the quiet of the yurt park, the smell of wildflowers and newly split wood, the little white structures sprinkled across the grass. The people carrying their dishes in little tubs. I was an unlikely candidate to live there as I had only been camping twice in my life. I had never started a fire or cut wood. I thought headlamps were hilarious and associated them with miners. Now I use one every day so I don’t stumble into a bison on my way to the bath house.

David understood the work from the beginning. We have been here for four winters, which is how you count years in Jackson Hole. You don’t realize all of someone’s latent, hidden talents until you live in a 20-foot yurt together. He is good with an ax, a hard worker, and can climb on top of the yurt like a monkey. His fires stay lit when he makes them—me, I am still 50/50 on that one.

Courtesy of Grace Hammond

The Yurt Park is home to 13 yurts, 18 people, 6 dogs, 3 cats, and 20 chickens. The yurt is perfectly round with a glass dome on top that allows me to watch the stars from my bed. Its walls are canvas and insulated with blankets, and a 30-year-old wood stove keeps it warm during the longest of winters. It has electricity but no running water—all the residents there share a bath house, with one sink for dishes, three bathroom stalls, three showers, and a handful of washers and dryers. Our community is close-knit and collaborative, and it runs a lot like a co-op.

We are exceedingly blessed to live where we do. The yurt isn’t a house—it’s a constant project, a lifestyle, and you learn to know it the same way a sailor knows his ship. It surprises us, challenges us, delights us, and is a partner in our lives.

Live in an interesting place or interesting way? Let us know. Send pictures and an answer to the question "Where I live, and why," to alum.mag@oberlin.edu