Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Spring 2012 Vol. 107 No. 2

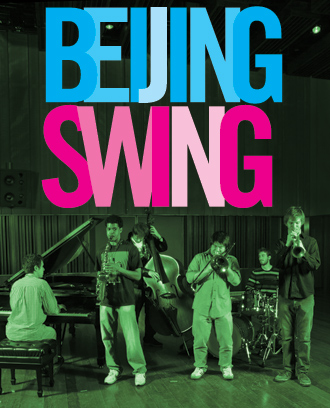

Beijing Swing

JAZZ WINTER TERM HEATS UP CHINA'S CAPITAL CITY

The 2012 Terry Hsieh Collective, from left: fifth-year Jacob Baron (keys), junior Alexander Cummings (saxophone), double-degree senior Matt Adomeit (bass), fifth-year Terry Hsieh (trombone), senior Peter Manheim (drums), and senior Pat Adams (trumpet).

The 2012 Terry Hsieh Collective, from left: fifth-year Jacob Baron (keys), junior Alexander Cummings (saxophone), double-degree senior Matt Adomeit (bass), fifth-year Terry Hsieh (trombone), senior Peter Manheim (drums), and senior Pat Adams (trumpet).

Senior Pat Adams on trumpet during rehearsal for the Terry Hsieh Collective.

Senior Pat Adams on trumpet during rehearsal for the Terry Hsieh Collective.

Members of the Terry Hsieh Collective pay a visit to the Great Wall of China. From left: fifth-year Jacob Baron, junior Alexander Cummings, Jackson Hill ’10, senior Peter Manheim, and senior Pat Adams. (Courtesy of Terry Hsieh)

Members of the Terry Hsieh Collective pay a visit to the Great Wall of China. From left: fifth-year Jacob Baron, junior Alexander Cummings, Jackson Hill ’10, senior Peter Manheim, and senior Pat Adams. (Courtesy of Terry Hsieh)

Double-degree fifth-year student Jacob Baron tickles the ivories during practice for the Terry Hsieh Collective.

Double-degree fifth-year student Jacob Baron tickles the ivories during practice for the Terry Hsieh Collective.

In the summer of 2009, double-degree student Terry Hsieh was studying Mandarin in Beijing. While doing language exercises one evening, he decided to take a break and explore a new neighborhood. He pointed to a random spot on a map of the city, and landed on the Hou Hai ("rear lake") bar district. Hsieh wandered around the neighborhood until he stumbled upon East Shore Live Jazz Club, a tiny, dingy bar with a sign in English advertising live jazz. Hsieh, a jazz musician in the conservatory, decided to head inside, unsure of what to expect.

Hsieh didn’t know it at the time, but he had happened upon a small yet vibrant pocket of the Beijing music scene, composed of a tight-knit group of local jazz musicians. The quartet Hsieh saw at the East Shore Live Jazz Club played music that was at once nothing like — and exactly like — what Hsieh studied as a trombonist in the conservatory. "They were coming up with their own take on the jazz sound," Hsieh says. "I was like, ‘Wow, I have to get to know these guys.’"

MY GOAL FOR THE PROJECT WAS TO BRING TWO COUNTRIES TOGETHER FOR MUTUAL APPRECIATION OF THIS ART FORM, BY MAKING MUSIC THAT SPEAKS TO THEIR EXPERIENCES."

Over the course of the next few weeks, Hsieh found himself becoming more and more immersed in the city’s jazz scene, befriending local musicians and attending jam sessions. Soon after his chance discovery, a mutual friend introduced him to Henry Zhang, the vice president of investment banking at Barclay’s Capital in Hong Kong and an avid jazz connoisseur. Zhang offered Hsieh $6,000 to bring a group of Oberlin jazz musicians to Beijing for a few weeks, a proposition that Hsieh enthusiastically accepted.

Since 2010, Hsieh has led his Terry Hsieh Collective on a tour of Beijing’s most swinging jazz clubs every winter term. For three weeks in January, the five-piece collective performs at music venues throughout the city, participating in workshops and jam sessions with world-renowned jazz musicians. They also teach master classes and lead recitals at the International School in Beijing (ISB), a nonprofit, private school in Shunyi province with a thriving jazz performance program.

This winter term, the lineup featured Hsieh on trombone, conservatory junior Alexander Cummings on saxophone, double-degree fifth-year Jacob Baron on keys, conservatory senior Peter Manheim on drums, and conservatory senior Patrick Adams on trumpet. Jackson Hill ’10, a conservatory graduate currently working in Beijing, joined them on bass.

Although members of the collective had the opportunity to take in the sights and sounds of Beijing in between gigs, Hsieh viewed the trip as nothing less than an artistic exchange between two cultures. "Most Chinese people don’t know much about jazz — the vocabulary is completely foreign to them," Hsieh says. "My goal for the project was to bring two countries together for mutual appreciation of this art form, by making music that speaks to their experiences."

Indeed, the history of jazz in the People’s Republic of China is as complex as the art of improvisation itself. Although it thrived in Shanghai in the 1920s and early ’30s, jazz was banned by the Chinese government during the Cultural Revolution, along with other musical genres that were considered examples of bourgeois self-indulgence.

Consequently, most Chinese musicians are trained in more traditional performance styles, which emphasize discipline and moderation over the unrestrained, freewheeling aesthetic characteristic of contemporary jazz music. "Chinese musicians are influenced by classical music," a local jazz club owner told the lifestyle website Beijingscene.com. "They follow the bass, but there is no freedom or creativity."

Despite the relative difficulties of introducing a Western art form to Chinese audiences, however, jazz is steadily gaining a foothold in the Chinese music scene, Hsieh says. Jazz music is gradually becoming as integral to Chinese cultural identity as classical music, with Chinese musicians vying with Western musicians for top spots in international jazz competitions.

Just as classical performance is viewed as a reflection of national identity, many musicians consider the mastery of an American art form an assertion of national pride, Hsieh says. "In the States, jazz is taught as American classical music, so it’s treated as sort of a cultural relic. In China, jazz is new and modern, so it has more urgent political and national value."

While jazz’s burgeoning popularity makes it an exciting time to work as a musician in the People’s Republic of China, some audiences are still unsure what to make of a genre that falls somewhere in between American rock and classical music. In order to make jazz more palatable to a foreign audience, the collective performed arrangements of original compositions and American standards, with a distinctly Chinese folk or classical flavor.

"We made an effort to connect with them and learn about their culture, not just force ours onto them," drummer Peter Manheim says. "By trying to arrange Chinese songs in a jazz context, we showed that what we’re doing is relevant to what they’re doing, which puts us on the same page as the audience."

Manheim also plans to use his experience abroad as an opportunity to build relationships with Chinese jazz artists and American musicians working abroad, including Theo Croker ’07 and Alex Morris ’10, both conservatory jazz musicians who have lived in China. Manheim says that the relatively low cost of living in China, combined with an increased number of opportunities for gigs at local jazz clubs, have encouraged many struggling jazz musicians to seek out job opportunities there. "It’s feasible to make a comfortable living as a musician in China," Manheim says. "By networking and making connections, I sort of saw the trip as an investment for the future."

Hsieh hopes that the exchange of ideas between American and Chinese jazz musicians will ultimately manifest itself into an exchange of career opportunities. Through the connections he’s made in China, Hsieh hopes to establish an international booking agency that will introduce Chinese musicians to the American market and American musicians to the Chinese market; he is applying for an Oberlin Entrepreneurship Fellowship to finance the project. He is also working on his honors project, which explores the relationship between Chinese music and politics by comparing the development of jazz in Shanghai and Beijing.

Although a combination of careful planning, extensive rehearsals, and the aid of generous benefactors brought Hsieh and his collective to China every year, Hsieh acknowledges that luck — or the art of improvisation — has played a prominent role in the project. Had he not gotten bored and decided to go for a walk one balmy summer night, he never would have ended up playing at the jazz club he stumbled into that evening. "None of this would have happened if I had just sat still," he says. "Improvising is one of those fine arts that make you think on your feet. You roll with the changes and try to keep up, and every once in a while, a gem comes out."

EJ Dickson ’11, a fellow in the communications office, has written for nerve.com , Heeb magazine, and other publications.

The Shanghai Scene

Trumpeter Theo Croker '07 performs at the Kohl Building celebration. Croker lived in Shanghai for four years, playing in the house band for the Shanghai House of Blues and Jazz. (Photo by Kevin Reeves)

Trumpeter Theo Croker '07 performs at the Kohl Building celebration. Croker lived in Shanghai for four years, playing in the house band for the Shanghai House of Blues and Jazz. (Photo by Kevin Reeves)

Beijing is not the only city in the People’s Republic of China with a vibrant jazz scene. Since jazz’s reemergence in China, Shanghai has enjoyed a reputation as one of the swingingest cities on the continent. The city’s nightlife attracts highly trained musicians from across the globe. Shanghai offers a more affordable and less competitive environment than cities like New York and London, which have often been considered the primary hubs of the global jazz scene. And Chinese audiences are, for the most part, unfamiliar with the context of the jazz tradition. That gives musicians free rein to revitalize and reinvent the art form.

Andy Hunter ’02, a jazz trombonist and double-degree graduate, was one of the first Oberlin students to make inroads in Shanghai, relocating to the city in 2001 after receiving a Shansi grant. "When I first showed up in Shanghai, only a handful of foreign musicians were performing there," says Hunter, who is now based in New York. "Now it is a burgeoning international scene, with musicians coming from all over the globe. It was a rich experience, and I grew alongside the scene as I watched it explode." Though Hunter left Shanghai in 2008, he visits the city about once a year.

In 2005, Hunter returned to Oberlin to speak about his experiences in Shanghai as a guest panelist in an East Asian Studies Department-sponsored conference. Hunter’s talk inspired one of the students in attendance, trumpeter Theo Croker ’07, to move to Shanghai after graduation, where he was hired, along with bassist Rob Adkins ’05 and drummer Charlie Foldesh ’07, to play in the house band for the Shanghai House of Blues and Jazz. "It’s rare to get a gig like that in the United States," Hunter says. "In New York, it’s so competitive that it’s cheaper for jazz clubs to hire different musicians every night than to hire a house band. You have to fight to make the music you want to make and make a living at the same time."

Croker, who now lives in New York and is signed to jazz vocalist Dee Dee Bridgewater’s record label DDB Productions, says that living in Shanghai for four years allowed him to develop his business skills as a musician, providing him with more artistic and financial freedom than is usually available to musicians early in their careers. "When I lived in Shanghai, I was booking the club and hiring my own musicians," Croker says. "I can’t imagine any other place where you could go as a 22-year old and essentially build your own empire."

Before leaving Shanghai in 2011, Croker was commissioned to bring musicians to the jazz bar at the Peace Hotel, a local jazz landmark since the 1920s. He immediately enlisted bassist Curtis Ostle ’06, saxophonist Jonathan Parker ’08, and drummer Alex Ritz ’08 to play with him. "I think Oberlin students are more diverse and open to cultural differences," he says, "so it’s easier for them to adapt when they get there."

Along with Croker and Ostle, Foldesh played in the house band for Asia’s number-one English-speaking nighttime talk show, Asia Uncut, which aired in 53 countries throughout Asia and the Middle East. He also teaches music performance at the JZ School in Shanghai, a progressive learning institute founded by the renowned JZ Club that has also boasted Ostle, J.Q. Whitcomb ’02, and Eddy Goltz ’79 among its faculty members.

Now in his fifth year in China, Foldesh says that it’s been "pretty neat" to witness the evolution of the Shanghai jazz scene firsthand. "Since I first arrived in Shanghai, I’ve seen more people take an interest in live jazz than ever before," Foldesh says. "Instead of going to karaoke bars or dance clubs on the weekends, more people are willing to spend a few dollars to see us play. That’s one of the reasons I stayed in China, because I really feel like I’m taking part in something special."

– EJ Dickson ’11

To share your own jazz in China story, put your comments in the box below; to hear music from the musicians in this story, visit the following sites:

Terry Hsieh Collective

See also Terry's Oberlin Story

Theo Croker

Andy Hunter

Charlie Foldesh

Curtis Ostle

Alex Ritz

J.Q. Whitcomb

Eddy Goltz

Jonathan Parker

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.