title="Return to Table of Contents">Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Spring 2013 Vol. 108 No. 2

When Dan Rattigan '02 last returned to Costa Rica, where

he and his wife, Jael, briefly ran a café before decamping to North Carolina to make chocolate, he hand-delivered a chocolate bar to the farmer growing cacao beans expressly

for Rattigan's company.

"It's really cool to see the farmers feel pride in the end product," Rattigan says. "In most cases, the grower lacks

that connection."

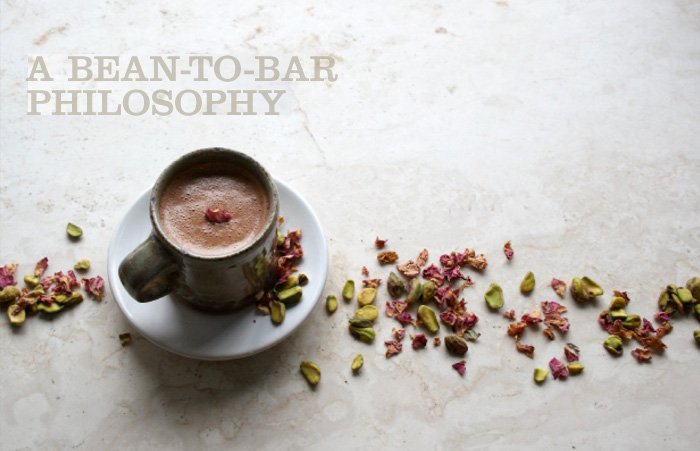

Five years after opening French Broad Chocolates, an offhandedly sophisticated chocolate salon that has since become a three-level community institution, the Rattigans are transforming their company from a standard small-batch confectionery into an ambitious bean-to-bar operation. They hired their former Costa Rican dishwasher, who's since established a small cacao plantation, to coordinate purchases from his neighbors; the first metric ton of Costa Rican beans will deliver this spring.

"We've been blessed with the ability to get into the provenance of our ingredients," Rattigan says. "We've done this with our milk, and we've done this with our fruits; chocolate has been the elephant in the room."

There are three dozen or so chocolatiers nationwide who have embraced a bean-to-bar philosophy, and they are drawn to the format for different reasons: "Some are hell-bent on exacting a perfect roast; others are trying to mimic the refined technique of larger-scale manufacturers," Rattigan explains. For French Broad, though, sourcing the beans directly from farmers provides the opportunity to correct an industry traditionally associated with environmental degradation, worker exploitation, and secrecy.

Costa Rica was a major producer of cacao until 1978, when a fungus blight wiped out the crop and forced growers to abandon their farms. Farmers who weathered the crisis had to contend with consumers' diminished opinion of their product, an enduring notion that has kept bean prices low.

But the Rattigans, who believe that quality hinges largely on farming and processing methods, have faith in Costa Rican chocolate. They've recruited other southern chocolate makers to join them in paying Costa Rican growers the prices typically commanded by organic, fair-trade beans from esteemed cacao regions.

"We can't exist entirely outside of the world cacao market, but we're trying to pave the way for a little bit of prosperity for the guys we're working with," Rattigan says.

Jael and Dan Rattigan '02, owners of French Broad Chocolates in Asheville,

North Carolina.

Jael and Dan Rattigan '02, owners of French Broad Chocolates in Asheville,

North Carolina.French Broad previously bought its chocolate from a Peruvian cooperative. While Rattigan describes that chocolate as "fruity," the trial batch of beans that went into the bar Rattigan took to Costa Rica was "much more earthy, with a little bit of nut."

Rattigan honed his culinary sensibilities at Oberlin as a member of Harkness and Old Barrows co-ops, where he served as head cook and lead baker. His dedication to food was so intense that he rejected his mother's graduation gift of a briefcase, asking for All-Clad cookware instead.

The autonomous attitude that inspired Rattigan's fellow co-opers to experiment with making their own tofu is evident at French Broad's year-old factory, which is equipped with a nib classifier, separator, and prototype solar cacao roaster designed by Rattigan.

The couple hopes to use Costa Rican chocolate in 30 percent of the bars, truffles, and caramels produced in the factory this year. They're guided by a lesson Rattigan says he learned in the kitchens of Oberlin's co-ops: "When you get a group of people together, you can make an enormous impact with your food dollars."

Hardworking Hedonist

French Broad Chocolates isn't the only Oberlin-run chocolate outfit. Two younger alums are making a splash with truffles in their hometowns.

An increasing number of sugar fans may be familiar with terms such as "single-origin" and "Dutch process," but there's still plenty of silliness surrounding chocolate, as Hedonist Artisan Chocolates' Nathaniel Mich '10 discovered while spending winter terms with the Rochester, New York, confectioner.

Mich was charged with creating themed chocolate sculptures for an annual charitable event: His "Mucho Caliente" entry was a ristra of oversized chili pepper ganache truffles, and he prepared a 20-pound coconut curry truffle for the "Under the Mandarin Moon" party.

But since joining Hedonist in 2011 as a full-time chocolatier, Mich has handled the more serious work of tempering chocolate, concocting creams and fillings, enrobing truffles, dipping fruit, and making bars and barks. As head chocolatier for a company whose salted caramel was praised by the New York Times this year for its "beautiful consistency," Mich is also responsible for developing new recipes. His first truffle collection debuts this spring.

"I had this visual of a tea party in a garden," he says of the featured flavors, including Earl Grey caramel, tarragon-carrot, and porcini mushroom with thyme.

Mich's first chocolate internship resulted from a "mid-college crisis" that worried his parents. He says they're no longer fretting about his career choice: "I get in trouble if I don't bring home the scraps."

Steffy, Not Stuffy

Detroit's thriving artisan food community was short a chocolatier until Pete Steffy '08 started hand-rolling truffles in his home kitchen.

Steffy hadn't planned to sell his truffles, but friends' requests led to farmers' market stints. He's now moving into a commercial kitchen and hopes to eventually establish a storefront.

"It's all happened very organically," Steffy says. While dabbling in cooking as a co-op member at Oberlin, Steffy encountered chocolate while teaching English in Chiapas, Mexico. He paid $50 for a private class with a chocolatier, later honing his signature, unfussy style while studying at Schoolcraft College's culinary school.

"I have a unique aesthetic," says Steffy, who pays the bills by working shifts in a neighborhood deli and offering bass guitar lessons. "A lot of chocolatiers in the suburbs have standard brown and pink truffles with French names. I'm very down-to-earth with my packaging."

The truffles within the packages are slightly more baroque: current flavors include rosemary sea salt, cinnamon cayenne, and candied ginger.

"They're very delicate," Steffy says. "And very rich."

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.