Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Summer-Fall 2010 Vol. 105 No. 4

Before & AFTER

JAZZ at Oberlin

There’s something new and gleaming on the Oberlin campus, a glowing nexus of light and sound and big ideas. Brushed aluminum, glass, and wood wrapped around 37,000 square feet—yes, a building—but one that expresses the striving of generations of Oberlin students and the spirit of America’s great musical gift to the world.

The 37,000-square-foot, three-story Kohl Building features a world-class recording studio, a glass-enclosed social hub for interaction, and an archive for the largest private jazz recording collection in America, among other features. Opposite page: A recording of the concert that Wendell Logan called "a watershed event" for jazz. (photo by Kevin Reeves, courtesy of Westlake Reed Leskosky)

The 37,000-square-foot, three-story Kohl Building features a world-class recording studio, a glass-enclosed social hub for interaction, and an archive for the largest private jazz recording collection in America, among other features. Opposite page: A recording of the concert that Wendell Logan called "a watershed event" for jazz. (photo by Kevin Reeves, courtesy of Westlake Reed Leskosky)

The Bertram and Judith Kohl Building—now home to the Oberlin Conservatory of Music’s programs in jazz studies, music history, and music theory—opened May 1 to great fanfare. Bill Cosby and Stevie Wonder thrilled the throng. Oberlin’s jazz luminaries returned in force to perform, including James McBride ’70, Farnell Newton ’99, Theo Croker ’07, Stanley Cowell ’62, Jon Jang ’78, and Leon Dorsey ’81. The celebration even enfolded the broader community, with the Oberlin orchestra and Stevie Wonder giving a special concert for local schoolchildren and their parents.

For many alumni, the inauguration of the new building capped a lifelong passion for jazz that began even before they arrived as wide-eyed first-year students. This passion hasn’t always been nurtured at Oberlin. Elite conservatories across the country spurned jazz as a passing fad during most of the 20th century. Oberlin wasn’t much different.

"This is a complete 180-degree turnaround," says James Neumann ’58, who was active in Oberlin’s jazz club back in the days when aficionados were hip outliers and visiting jazz artists weren’t allowed to use the conservatory’s exquisite pianos. "It’s unbelievable to see the school embrace jazz like this, with a building that probably represents the most conspicuous statement about this art form in all of higher education. It’s like a dream."

"How did we get from there to here?" asked Dean of the Conservatory David Stull ’89 during the opening weekend. "The answer is Wendell Logan." The audience responded with a storm of applause as Stull announced that the new building’s commons area would be named for the revered jazz studies chair and professor of African American music.

Logan died several weeks later (see below), before this writer had a chance to speak with him. But he offered this recent reflection to Anna Ernst ’10 for a paper on the history of jazz at Oberlin: "The spirit of the music prevailed," he told Ernst. "We were educated to break down barriers no matter where they existed, and it fell upon me to do that. I feel blessed that I was the one chosen to do that.

"We are here to teach a language," he added.

Wendell Logan, founder and chair of the jazz studies department and professor of African American music at the conservatory, died June 15, just a short time after the opening of the Kohl Building.

The Kohl Building represents the culmination of Logan’s efforts to create a permanent home for jazz at Oberlin, dating back to 1973 when he joined the faculty. The building’s opening celebration brought scores of jazz alumni back to campus, including many who studied under Logan’s leadership. At nearly every event throughout the weekend, he was recognized with tributes from the stage and enthusiastic applause from audiences who registered their appreciation for his devotion to jazz and to musical education.

An obituary for Professor Logan appears on the final page of this magazine.

The Roots of Jazz at Oberlin

Anna Ernst discovered that jazz first made its way to Oberlin back in the 1940s, when the Frank Williams Combo performed in Finney Chapel. "Holy Smokes! Jazz Concert in Chapel" squawked the Oberlin News-Tribune on October 5, 1944. A native Ohioan and a worker at the Lorain shipyards, Williams was admitted to the conservatory two years later under the G.I. Bill. There he stayed until 1949, when he left to support his family by working at a chemical company. Remarkably, he auditioned at the conservatory 30 years later, after he retired, and was readmitted. He finished his degree in piano at the age of 64. Williams’ senior recital, Ernst found, included Debussy, Scarlatti, Liszt, and Chopin, as well as the jazz tunes "Misty," "Stelle by Starlight," and "Take the A Train."

Much had happened during the 30 years between Williams’ anomalous first performance and his senior recital. Growing numbers of students were interested in jazz and were determined to bring great jazz performers to campus. In 1953, they scored a coup that not only changed Oberlin’s relationship with this great American art form, but also jolted the jazz community nationwide. A student named Jim Newman ’55 arrived fresh from the jazz scene in San Francisco, where he’d hung out at a club called the Black Hawk and became friends with a young jazz artist named Dave Brubeck. Now a superstar—and still touring at age 90—Brubeck was struggling for recognition then. When Newman suggested that he play a gig at Oberlin, Brubeck eagerly assented.

Newman and other jazz fans spread through the region with posters, anxious to draw a crowd. They loaded the jukebox in the college recreation center with Brubeck’s records, hoping to build a constituency among the other students. "A lot of people heard his music for the first time on that jukebox," says Newman, now involved with a musical organization called Other Minds that brings composers to San Francisco.

Their hard work paid off. The Dave Brubeck Quartet filled Finney Chapel with students from both the college and the conservatory. Brubeck remembers that audience as one of the most respectful and appreciative of his career. "They knew what we were doing in counterpoint and melodic lines and harmonic progression—they were way ahead of their teachers," he says. "You’re always listening to and judging an audience as they’re listening to and judging you. You play a quote from Stravinsky, you throw in some Bach quotes, some little phrases from popular songs. It’s like a speaker telling a joke; some audiences get it, some don’t. Did those students at Oberlin get it? Oh yeah."

The campus radio station recorded the concert, and Brubeck’s label, Fantasy Records, produced a landmark album called Jazz at Oberlin. The album not only boosted Brubeck’s career, but it also changed the way the public would experience jazz in the future. Wendell Logan called the Brubeck concert the "watershed event that signaled the change of performance space for jazz from the nightclub to the concert hall." Logan said that nationally known jazz bands had come to Oberlin before, but mainly to play at dances. "The trend of going to a jazz concert simply to listen was a novel idea, and the Brubeck concert was a major factor in starting that trend."

After the Brubeck concert, students formed a campus jazz club that brought Brubeck back to campus the following year. They went on to host concerts by other jazz legends including Count Basie, Chet Baker, and Teddy Charles in a group that featured Charles Mingus on bass.

But even as momentum grew among the students, the conservatory did not exactly embrace jazz or welcome these visiting artists. Famously, the conservatory wouldn’t allow Brubeck to use one of its fine pianos for the 1953 concert, sending students scrambling to rent one elsewhere. "Institutions like the conservatory are dedicated to preserving the canon, and the canon, by its nature, resists incursion," says Stull. "The canon is all about work that survives the blowtorch of time. Those experiences by the early jazz artists reflected an ultraconservatism that existed relative to music generally. In fact, there was a huge fight among our faculty at the turn of the 20th century about whether to have a piano major here. One of the organists said, ‘Why would we have a major in an instrument that is often found in brothels?’"

Ultimately, the growing enthusiasm for jazz from several quarters began to open doors at the conservatory. According to Ernst’s research, the Oberlin College Alliance for Black Culture requested classes in jazz and blues in the late 1960s. The conservatory contacted Logan in the early 1970s to ask if he was interested in developing a program of African American music. He came to Oberlin in 1973 and established the Oberlin Jazz Ensemble the following year. He recruited award-winning composers, arrangers, and performers to join the faculty.

"I had never even thought about teaching—that was the case for all of us—but Wendell wanted to have professionals teach students how to be professionals," says Professor of Guitar Bobby Ferrazza, now in his 23rd year on the faculty. "And once I started teaching here, I loved it. You get used to being surrounded by bright, stimulating people. You know you don’t find that everywhere."

In 1989, jazz studies became an official major. However, the department remained housed in shabby old Hales Gym a long walk from the conservatory.

Old School Jazz

A student practices at the old Hales Gym, where jazz studies occupied whatever space was available for about 30 years. (photo by Samuel Lawrence)

A student practices at the old Hales Gym, where jazz studies occupied whatever space was available for about 30 years. (photo by Samuel Lawrence)

For three decades, jazz studies occupied whatever space was available in Hales Gym. Although Wendell Logan felt that the run-down building had some soul to it, it pained him when parents would come and visit and get a negative impression of the program. "But I will say one thing," Logan said at the Kohl Building dedication, "the saving grace was when they came in to hear the band. They’d say, ‘Oh!’"

Senior visual arts student Sam Lawrence documented the last two years of jazz at Hales Gym in photographs, which he donated to the Kohl Building and which he has compiled into a book. The collection, says Lawrence in his artist’s statement, shows how the students and teachers transcended their environment and was created "as a Hales memorial, to help past, present, and future students and faculty remember the passion and perseverance that have made Oberlin jazz what it is today." To find out how to purchase his book, send an e-mail query to Samuel.Lawrence@oberlin.edu.

Architecture as Fusion

Wendell Logan with students. (photo by Samuel Lawrence)

Wendell Logan with students. (photo by Samuel Lawrence)

When David Stull became dean of the conservatory in 2004, one of his first goals was to move jazz studies into a facility that both supported its work and reflected its stature as a world-class program. And he wanted to unite jazz studies with the rest of the conservatory. "You want the faculty, the students, and the music all in one place," he says. "Music evolves because of creative impulses that are shared between diverse artists. To continue our rich musical tradition, we needed a facility that encouraged that."

Oberlin’s jazz and classical students have always had some contact with each other, but the benefits of greater connection make sense to former students who are now professionals—even if they hail from the days when jazz was outsider music. "There’s a greater demand for classical singers to have some experience with jazz," says Anne Phillips ’56, who performed in an opening act before Brubeck’s 1953 concert and is now a singer, composer, and arranger in New York. "They become freer and have a deeper understanding of the lyric and the story."

"Classical and jazz are like different languages," says composer and pianist Jon Jang. "We encourage people to go beyond English only and become bilingual or trilingual. We have to be open to diverse musical languages."

The many expectations for the building were laid in the hands of Cleveland firm Westlake Reed Leskosky, which, in turn, laid them in the hands of a recent graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Jonathan Kurtz. The resulting building—constructed on a lot just east of the conservatory—is both airy and elegant, with a bridge that connects to the conservatory buildings and hoists a glittering aerie, called the Sky Lounge, with great views of campus.

Cleveland Plain Dealer architecture critic Steve Litt gave the building a glowing review, writing "Kohl is one of the best new buildings in Northeast Ohio designed by any architecture firm—local or otherwise—in recent years."

The Kohl building boasts a superb recording studio, one large enough to host a chamber orchestra and practice rooms that are equipped with recording equipment and wi-fi. It also houses two important collections: the Selch Collection of American Music History, including instruments and artifacts, and the James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection, believed to be the largest private collection of jazz recordings (more than 100,000 albums and 40,000 CDs), documents, posters, and more. The conservatory plans to disseminate the Neumann collection digitally. Posters and others images from the collection will flow through the building via flat-screen monitors on every floor. In their practice rooms, students can download all the various versions of jazz standards and compare the styles and techniques. They can also record themselves, plays it back, and listen to their own sound.

"Ultimately, we’ll judge the building not by its appearance or by what architecture critics write about it," says Stewart Kohl. "We’ll judge it by how it performs, by how it helps what Oberlin does for a living, which is to take these young and talented musicians and help them develop. I think it will perform splendidly."

So far, the building is doing its job. Designed to invite entry from a public walkway, the Kohl Building draws a steady stream of students and visitors. Impromptu combos gather on its stairs and upper patio garden.

"It’s a very pretty building," says Julia Chen ’12, a double-degree student majoring in jazz piano and psychology. "I think everyone in jazz studies finally feels they’re included in all the benefits Oberlin has to offer. I heard some people started to cry when they first walked in."

See photos and videos of the Kohl Building and its dedication weekend at www.oberlin.edu/kohl.

Kristin Ohlson is the Cleveland-based author of the memoir Stalking the Divine and coauthor of Kabul Beauty School.

Jazz Accompaniment

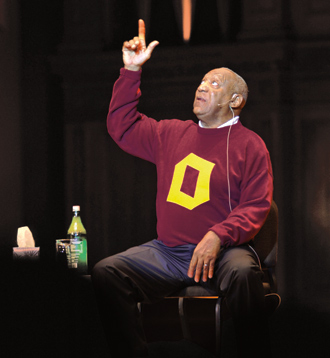

Bill Cosby at Finney Chapel. (photo by Kevin Reeves)

Bill Cosby at Finney Chapel. (photo by Kevin Reeves)

The opening of the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building was celebrated with a weekend extravaganza that included appearances by Stevie Wonder, Bill Cosby, Avery Brooks ’70, and some of the biggest names among Oberlin’s jazz-playing alumni, along with a moving dedication ceremony, the conferring of honorary degrees, panel discussions on the building’s design, and, of course, live music all over campus.

On Friday, April 30, Cosby performed a comedy concert in a packed Finney Chapel. Opening the performance was composer and pianist Stanley Cowell ’62, a Cosby favorite. A long-time supporter of the college, Cosby had the audience howling with his comic storytelling, which touched on such topics as his first-time experiences with jazz music, the amazing acrobatics involved in the dances couples performed when he was growing up, and the joys and perils of his childhood. "When I was 6 there was no TV," he said. "I don’t mean in my house. There was no TV anywhere."

Earlier on Friday, Cosby and his wife, philanthropist Camille Cosby, were awarded honorary Doctor of Humanities degrees, while Stevie Wonder was awarded an honorary Doctor of Music degree. "Like true Oberlinians, Bill and Camille Cosby and Stevie Wonder believe that education empowers," said President Marvin Krislov at the Tappan Square ceremony. "On this glorious day, we at Oberlin can say, ‘Dr. Cosby, Dr. Cosby, Dr. Wonder, you have brought sunshine into our lives.’"

The formal dedication of the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building on Saturday, May 1, began with the sounds of live jazz in Warner Concert Hall and a dramatic delivery by actor Avery Brooks ’70 of the Henry Dumas poem "Play Ebony, Play Ivory." The dedication concluded with a ribbon-cutting ceremony and a champagne toast in the Bert and Judy Kohl Garden that extends from the building’s third floor.

Designer Jonathan Kurtz of the architectural firm Westlake Reed Leskosky emphasized how the excellence and determination of the people he worked with at Oberlin inspired the entire team. He described his task as creating "a socially dynamic place to bring together people for whom excellence is just a habit."

"Music is a fundamental part of the Oberlin experience—not just for conservatory students, but for a large majority of arts and sciences students as well," remarked Robert Lemle ’75, chair of Oberlin’s Board of Trustees. "The Kohl Building literally embodies the idea that music is vital to life at Oberlin."

Recognizing the pivotal role Wendell Logan had played in the history of jazz at Oberlin, Dean David Stull announced that the building’s commons area would be named for the revered professor of African American music and jazz studies chair. Logan ended the ceremony with the advice he always gave to his students: "Make sure the focus is on the music."

Students got a sneak peek of the building the day before, dodging "wet paint" signs and construction workers who were still adding finishing touches. "This is the coolest thing ever," said viola performance and religion major Mandy Hogan ’13. "The vibe, feel of it, and the colors are so jazz." The building’s new state-of-the-art recording studio—a wood-encased, two-story room connected to a cutting-edge control center featuring digital and analog recording equipment—garnered some of the most awed student reactions. Said one student upon entering: "Epic."

Jonathan Kurtz, Avery Brooks, Wendell Logan, and David Stull at the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building dedication.

Jonathan Kurtz, Avery Brooks, Wendell Logan, and David Stull at the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building dedication.

Also on Saturday, during an interview conducted by Caroline Jackson Smith, professor of theater and African American studies, Avery Brooks spoke about the convergence of music, dance, and spoken word in his life as an actor and artist. Describing Oberlin’s programs related to jazz music and culture, Brooks said, "I don’t know of any other place that exists that celebrates the history, the lineage, of arguably the other classical music in the world."

Concluding the celebration was a momentous concert in Finney Chapel, featuring special guest Stevie Wonder. Stull welcomed the audience with a message he was asked to relay to the Oberlin community from President Barack Obama when accepting the National Medal of the Arts earlier this year: "Tell your team you’re doing a great job."

Stull also lauded Logan for his important role in building the program. "We should let Wendell Logan know what he means to us," he said. The audience responded with thunderous applause.

Wonder performed such pop masterpieces as "I Can’t Help It" and "Superstition," while musicians James McBride ’79, Farnell Newton ’99, Theo Croker ’07, Stanley Cowell ’62, Jon Jang ’78, and Leon Dorsey ’81 (who also served as artistic director) kept audience members on the edges of their seats—and some dancing in the aisles. Overflow seating for the concert was provided at Warner Concert Hall and the Apollo Theatre, which reached full capacity. The Oberlin Jazz Ensemble provided backup and stepped out on its own with a full-force medley of some of Wonder’s best-loved songs, under Logan’s baton.

That wasn’t Wonder’s only Oberlin performance, however. He hosted students from the Oberlin City Schools and their parents in a performance of "Sketches of a Life," the composition he premiered in 2009 when he received the Library of Congress’s second Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. He was joined by members of the Oberlin Orchestra and conductor Bridget-Michaele Reischl. As a surprise treat, he also performed his hit "My Cherie Amour."

Gathering Raves

(photo by Kevin Reeves, courtesy of Westlake Reed Leskosky)

(photo by Kevin Reeves, courtesy of Westlake Reed Leskosky)

The Bertram and Judith Kohl Building was gathering raves even before it opened, including winning the American Institute of Architects Western Mountain Region 2009 Award for Unbuilt Work. But the ground-breaking work is also earth-friendly: its green building practices and sustainable strategies include geothermal heating and cooling with radiant panels, energy efficient systems and lighting, roof gardens, storm water run-off collection and filtration, and the use of local, recycled, and sustainably harvested materials.

The 37,000-square-foot, three-story building features a world-class recording studio, flexible rehearsal and performance spaces, teaching studios and practice rooms, a glass-enclosed social hub for interaction, and an archive for the largest private jazz recording collection in America, which includes rare musical instruments and a rare collection of jazz photographs from the 1950s, among other holdings.

The building’s materials, which include Brazilian ipé hardwood and, in a nod to Charles Martin Hall, aluminum from Alcoa, allow the quality of light within and without to change with the time of day and the seasons. "The wood of the building will take on a life of its own," says Jonathan C. Kurtz, Westlake Reed Leskosky associate and project designer.

At a panel discussion about the design, Kurtz joked about the parameters David Stull and others set for the building: It must be acoustically excellent, must have an intimate relationship with the landscape, and, finally, "build it in a parking lot."