Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Summer-Fall 2010 Vol. 105 No. 4

Q&A: Roland Baumann

The Oberlin Alumni Association of African Ancestry (OA4) held its annual reunion October 8 to 10, with the theme "Since 1835: Building on Our Legacy; Celebrating 175 Years of African American Heritage at Oberlin College."

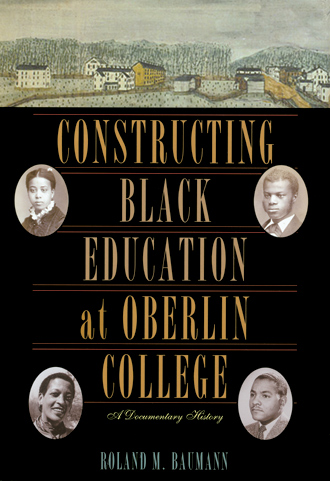

Each reunion registrant received Constructing Black Education at Oberlin College: A Documentary History, a new book by retired Oberlin College archivist Roland Baumann. Jeff Hagan ’86, editor of the Oberlin Alumni Magazine, asked Baumann a few questions about writing the book.

For more information about the reunion, visit http://oberlina4.ning.com, and look for coverage of the event in a future issue of OAM.

The Outlook Now

Roland Baumann’s book on African American education at Oberlin College reveals a commitment with a complicated history. The story today, based on this year’s admissions numbers, shows real progress.

As of this writing, American students of color comprise 24 percent of the new class, making this the most diverse class in Oberlin’s history in terms of percentage. The number of enrolling African American students is the highest since 1987. Also, Oberlin reached an all-time record number of Latino/a students, and the number of Asian Pacific Americans enrolling represents a slight rise from last year.

What were the important findings you uncovered

in your research?

First, Oberlin’s transformative commitment to admit students "irrespective of color" is a story of fractured progress. By 1900, Oberlin College had admitted and graduated more black students than any other white majority institution in the North. So Oberlin can easily lay claim to being the pioneer; it can also take credit for having elevated the voices of African American students and in having led the way in breaking barriers in society. Nevertheless, had it not been for constant student agency, Oberlin College would have been less inclusive, and access and opportunity for minority people would have proceeded at a slower pace.

Are there any misconceptions about Oberlin’s

history that have persisted?

First, Oberlin is not the first institution, but probably the fifth or sixth, to admit black students. Second, Oberlin College adopted discriminatory practices in terms of housing and literacy societies. Third, it seemed to embrace Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist philosophy that claimed that blacks had to earn equality status and build their character before they could be accepted in American society, as opposed to W.E.B. DuBois’ more activist civil rights advocacy. Finally, in writing this book I discovered that Oberlin College’s administration and faculty are far more conservative than the student body, almost at all times, and that this institution all too often had been slow to act in critical moments in its history. Oberlin College is an incrementalist place!

In terms of black higher education over the years, how does Oberlin compare with other institutions?

The Oberlin Collegiate Institute (renamed Oberlin College in 1850) will forever be recognized for its pioneer status. Oberlin served as the diversity model for other institutions of higher education up to 1970.

Presently, Oberlin College must compete with 30 or 40 other elite colleges and universities for the small number of highly qualified African Americans who can meet the admission requirements. In the past, admissions personnel were able to count on Oberlin’s reputation as a welcoming place and its inclusion on a list of feeder high schools—public and private. Now, they partner with organizations such as Quest Bridge Foundation, POSSE Foundation (Pathways to Student Success and Excellence), and others to attract students of color and first-generation college-bound. This is a more difficult, complicated struggle for the college today than it was immediately after World War II.

How did the idea for writing the book come about?

Reading Geoffrey Blodgett’s article "Myth and Reality in Oberlin History" in an Oberlin Alumni Magazine from 1972 initially alerted me that Oberlin’s celebrated black admissions story was one likely requiring further explanation to separate myth from reality, fact from fiction. I felt that serious research was needed to get beyond Oberlin’s "golden age"—the period of 1835 to 1865. To write about the first 30 years had become safe space. Except for Oberlin’s first archivist, William E. Bigglestone, no one locally had confronted the racially and culturally diverse history of the institution.

My decade-long collaboration with African American studies professor Adrienne Lash Jones in the course Researching and Writing African American Women’s History brought to the fore relevant documents from the late 19th century. One paper written in the course, "Black Women and Oberlin College in the Age of Jim Crow," by David A. Diepenbrock ’88, was published by the UCLA Historical Journal in 1993. This was the type of revisionist history that I encouraged Oberlin students to produce.

Nat Brandt’s award-winning 1990 book, The Town That Started the Civil War, about the pivotal story of the 1858 Oberlin Wellington Rescue and black participation in it, also whetted my curiosity and interest.