|

|

|

||||

|

|

The details of Oberlin’s first mock convention have been lost to history. No one can say whether Abraham Lincoln won the Oberlin nomination in 1860, as he did in real life. What is known is that Oberlin spurned him four years later, when the students instead nominated Ohioan Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln’s secretary of the treasury.

Oberlin often got it wrong, as it did this year when students selected Vermont Governor Howard Dean. Other Oberlin nominees who failed to get their party’s nod included U.S. Senator George Edmunds (1880 and 1884) and Owen D. Young (1932), a lawyer and statesman. But then, getting it right wasn’t the point. The convention was meant to be educational, entertaining, and fun. It was also an enormous amount of work. In conjunction with the 1968 convention, for instance, organizers brought in 50 speakers throughout the course of the year to address the Vietnam War and other issues of the day, says convention chair Bill McClintock ’68. In its heyday, the Oberlin convention was recognized as a national event, often drawing major media attention. No one could predict the winners—or other events that would unfold. In 1956, for instance, New Jersey Governor Robert Meyner delivered the keynote speech, and while there met Helen Stevenson, the daughter of Oberlin’s president. They later married. But perhaps the best way to appreciate Oberlin’s mock conventions is to relive them. Here are but two notable examples: 1936: As Oberlin Goes, So Goes the Nation

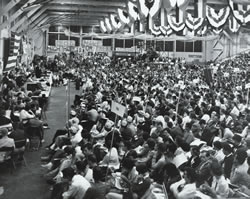

The four Oberlin classes that hosted the 1936 mock convention included eight men who would die in World War II. The convention and the days leading up to it offered a respite from the crumbling world, and its organizers managed to focus on a most pressing task—finding a live elephant to lead the Republican parade through Oberlin. For a while, they’d had the problem licked. A circus in Cleveland had agreed to rent them an elephant for $110—an enormous sum, given that a year’s tuition at Oberlin was $250. The trusting student organizers prepaid. But as the big day approached, the circus folded; two stunned convention organizers learned the news in the morning paper. With contract in hand, they skipped classes and raced into Cleveland, where they cornered a former circus official at a local hotel. “Don’t ask me,” the man grumbled. “They owe me $275.” The students were undeterred. Since they couldn’t get by with another cow—nor land a live pachyderm—they settled for an enormous paper maché elephant rented for $60 from the Cleveland Artificial Flower Company. On parade day, the replica elephant was pulled grandly through the streets of Oberlin—a female freshman riding on top—as 5,000 spectators looked on. The convention took place inside a tent packed with 3,000 delegates and onlookers. The delegates included a young Jesse Philips ’37, who went on to build a Fortune 500 company from scratch and become the principle donor for Philips Gymnasium. For the first time, parts of the proceedings were carried coast-to-coast via radio, and the event drew national media attention, including two pieces in the New York Times. Next Page >> |