Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Summer 2007 Vol. 103 No. 1

Around Tappan Square

Shansi Fellows Jesse Gerstin and Sarah J. Newman, both ’07, will spend two years in Indonesia.

Shansi Fellows Jesse Gerstin and Sarah J. Newman, both ’07, will spend two years in Indonesia.

Sojourn in Sumatra: Shansi partners with second Indonesian campus

Inaugurating a brand new partnership between Oberlin Shansi and a second Indonesian institution are May 2007 graduates Jesse Gerstin and Sarah J. Newman. Both Shansi Fellows will spend the next two years on the island of Sumatra teaching English at Syiah Kuala University (better knows as UnSyiah) and volunteering with local NGOs.

With a campus of 25,000 students and 2,000 faculty members, UnSyiah is the sole secular university in its region and is considered one of the most prestigious. The school was hard hit by the tsunami of December 2004, with more than 1,400 students and 120 faculty members losing their lives. Many others lost their housing.

Gerstin and Newman began their journey in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, over the summer, where they studied the national language of Bahasa Indonesia before moving on to UnSyiah. Each will spend 14 hours a week teaching English, both at the university’s central language-teaching center and in a department of their choosing. Gerstin will work with the economics department, teaching English to business students and faculty. Newman, who speaks French, Spanish, and Arabic, hopes to work in the gender studies program.

“There’s so much work to be done in setting up the program, being its first Fellows —it’s exciting,” says Gerstin. A French and Third World studies major, he hopes to become involved with the Tsunami Research Center in Banda Aceh, perhaps as a translator. Oberlin Economics Professor James Zinser, a Shansi board member who visited the region last March, says that he and UnSyiah economics professors are considering a collaborative research project on post-tsunami economic development there.

“This new Shansi partnership will engage Oberlin with one of the oldest Islamic com-munities in southeast Asia,” says Shansi Associate Director Deborah Cocco. “We really believe that Americans need to be engaged with Indonesia, and that we need to learn from each other. It’s a growing, developing society, and it will be a really exciting experience to be there when things are changing and forming.”

Made possible by a generous gift from two 1966 Oberlin graduates, the UnSyiah partnership was approved by the Shansi Board of Trustees in May 2006 following a visit to the school by Executive Director Carl Jacobson and others. Shansi’s longstanding partnership with another Indonesian institution, Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, was reestablished in 2004 after a several-year suspension.

Mirroring Shansi’s other partnerships in Japan, China, and India, Oberlin will exchange both visiting faculty scholars and undergraduates (during winter term) with UnSyiah.

The 2006-07 class of Bonner Scholars celebrates the $4.5 million grant.

The 2006-07 class of Bonner Scholars celebrates the $4.5 million grant.

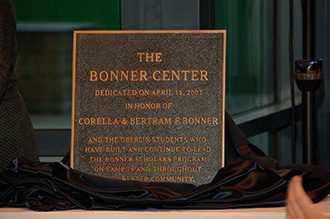

Oberlin Gains $4.5 Million from Bonner Foundation

The Bonner Foundation of Princeton, N.J., awarded Oberlin a $4.5 million grant in May to guarantee longtime continuation on campus of the Bonner Scholars Program, which promotes student service in the community. The award requires Oberlin to partially match the grant by raising an additional $2 million.

“We are ecstatic about the endowment,” says Director of Bonner Scholars Donna Russell. “The award guarantees longevity and greater visibility for the program on campus and within the national Bonner network.”

The Bonner Scholars Program, which was begun by Corella and Bertram F. Bonner in 1990, came to Oberlin in 1992. Each year, 60 students with high financial need—15 from each class year—are supported with a four-year community service scholarship of up to $15,500. In exchange, the students volunteer 10 hours a week with a program of their choice, such as America Reads, the Boys and Girls Club, El Centro De Servicios Sociales, Family Planning Services, the Kendal of Oberlin retirement community, or Oberlin Community Services. Until now, the Bonner Foundation funded the scholarships and other expenses annually. Of the 27 Bonner Scholar schools, about half have earned endowment funding.

“Oberlin is one of the defining institutions in America to champion the causes of liberal education, access, and diversity,” says Bonner Foundation President Wayne Meisel. “We were inspired by that vision and are equally committed to preserving and advancing it. I could not imagine the Bonner Scholars Program without Oberlin leading the way in what we do.”

To commemorate the award, the College’s Center for Service and Learning—which coordinates several community service programs—has been renamed the Bonner Center for Service and Learning.

Girls Gone Science

“These are geeky!”

“You look beautiful,” insists Emily Dodd ’07. “Just like a real scientist.”

To be certain, the middle school student scans her classmates seated inside the Science Center, noticing a girl with prescription eyeglasses looking apprehensively at the goggles in her hand.

“You can put the goggles over the glasses,” explains Doug Sheldon, a science teacher at Langston Middle School.

Soon everyone moves closer to Assistant Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Catherine Oertel, who begins her science presentation by mixing barium hydroxide and ammonium chloride in a glass, a motion that turns the solids into a solution. Once the beaker makes its way around the 15-member group, it’s on to the professor’s next trick—transforming water into a gas. Then, accompanied by a chorus of oohs and ahs, she lifts a large jug of liquid nitrogen, pours it into a bowl, and asks for a volunteer to place an inflated balloon on top.

Welcome to the spring field trip of the Girl’s Science Club.

Assistant Professor Catherine Oertel makes ice cream with girls from Langston Middle School.

Assistant Professor Catherine Oertel makes ice cream with girls from Langston Middle School.

“My sister and I had an awesome experience with a mentor in middle school. It got us interested in science, and we wanted to bring that to Oberlin,” says Emily, a theater major and chemistry minor. She and her sister, neuroscience major Laura Dodd ’07, started the club three years ago with Sheldon as their mentor.

“Historically, girls don’t get a push to go into science, so it’s important for them to be empowered,” says Laura. “Professor Oertel is doing a good job of explaining concepts. Typically we try to keep things light. The critical factor is to make science fun so the girls will become interested in it.” Laura, along with several club members, proudly wears the results of one such experiment: tie-dye T-shirts.

“A lot of the girls already have a healthy curiosity,” adds Sheldon. Like 12-year-old Narissa, who enthusiastically provides a laundry list of past experiments the club has conducted, including making soda pop.

Oertel, meanwhile, wraps up her “states of matter” lab with a demonstration to end all demonstrations: liquid nitrogen ice cream.

“We get just as excited as the girls do,” says Laura, as she and the group quickly stir their sticky concoctions of cream, sugar, and vanilla—puffs of smoke wafting down the sides.

The 11th Hour

Actor Leonardo DiCaprio’s new eco-documentary, The 11th Hour, features the opinions of some of the world’s most prominent thinkers and scientists: Mikhail Gorbachev, Stephen Hawking … and Oberlin’s own David Orr.

Produced and narrated by DiCaprio, the film takes a layman’s approach in seeking solutions to environmental crisis. Orr, who appears on screen and served as an advisor for the film, assisted directors in identifying themes and experts and in reviewing final cuts. “If the Earth were sent into a hospital emergency room,” Orr says, “the diagnosis would not be very good. But there is hope and there is time, just not much of it. This is the generation that has to move on these issues. This is the time, and we are the people.”

Best known for his pioneering work on environmental literacy in higher education, Orr is the Paul Sears Distinguished Professor of Environmental Studies and Politics at Oberlin and chair of the environmental studies program.

A glass wall separates the Mudd Commons café (before furniture) from the main study area.

A glass wall separates the Mudd Commons café (before furniture) from the main study area.

Library Latte

A $1.5 million Academic Commons opened on the main floor of the campus library this fall after months of extensive renovations to Mudd Learning Center.

Open daily until 2 a.m., the Commons allows more space for collaborative learning and interaction among students and faculty, says Ray English, Azariah Smith Root Director of Libraries. An attached café named for Azariah Root, the College’s first librarian, offers coffee, snacks, and a reading area with shelves of periodicals. A glass wall separates the café from the main Commons area, while cork flooring minimizes noise.

“We’re trying to make Mudd a better space for learning—more accessible and welcoming,” says English.

Besides, “If people already ‘live in the library,’ then they should be able to get a good cup of coffee,” adds student consultant Allison Choat ’07.

Housed along the building’s outer walls are six group study rooms outfitted with 42-inch LCDs, as well as media labs, multimedia presentation areas, and electronic classrooms. The center of the Commons area features bold, colorful “retro-modern but comfortable” furniture, as well as mobile collaborative workstations. Two bathrooms were added nearby.

English says that a second goal of the Commons was to bring together several support services, such as the Writing Center, Peer Academic Ambassadors, reference help, and student technology support. The circulation area has also been consolidated, with reserve and audio-visual materials being checked out from a single location.

Planning for the Academic Commons began two years ago, when the Faculty Library Committee reasoned that the Mudd Center, built in 1974, needed to better reflect the significant changes in student learning styles and educational technologies.

The Board of Trustees approved the $1.5 million dollar budget last March. As of August, $1.4 million had been raised for the project. Major donors include Mimi Halpern ’60, William G. Roe ’64, Sarah Sharpe ’82, and Charles ’64 and Anne ’62 McFarland. ATS

The Rosa Verona marble bowl is restored to its former luster at Fairplay Stonecarvers.

The Rosa Verona marble bowl is restored to its former luster at Fairplay Stonecarvers.

The bronze statue sits atop the fountain.

The bronze statue sits atop the fountain.

Historic Fountain Fixed the Wright Way

Thanks to a grassroots effort begun by family members and friends and aided by Oberlin’s Office of Development, the Katharine Wright Haskell Memorial Fountain has been restored to its former glory.

A $60,000 fundraising effort helped breathe new life into the deteriorated marble fountain, which was installed near the Allen Memorial Art Museum in 1931 to honor 1898 Oberlin alumna Katharine Wright Haskell, the sister of Orville and Wilbur Wright. Many people believe it was Katharine’s constant dedication, devotion, and advocacy that helped guarantee the Wrights’ aviation legacy.

With a teaching degree from Oberlin, Katharine became the second woman ever elected to the College’s Board of Trustees. In 1926, against the wishes of her brother Orville, she married journalist Henry Haskell, Class of 1896, a two-time Pulitzer-Prize winning reporter who eventually became the editor of the Kansas City Star.

After Katharine’s death from pneumonia at age 54, a bereft Haskell commissioned the hand-cut Italian marble fountain to be installed at Oberlin. Crowning the fountain was a bronze statue of a small boy playing with a dolphin—the exact replica of a Renaissance sculpture in Florence that the couple had seen on trips, says Katharine Wright Chaffee ’44, Katharine Haskell’s great niece.

But without funds for proper maintenance over the years, the fountain literally began crumbling to the ground. Its water stopped flowing years ago, and ribbons of yellow tape deterred visitors, wedding parties, and students from what once was a favorite spot for photographs.

“When I was a student at Oberlin, I was very much aware of the fountain. It was still quite beautiful,” Chaffee says. “But I felt ashamed to learn it had fallen into disrepair.”

Mary Winters Behm ’66 says she, too, was surprised to discover that the “wreck of a fountain” was linked to one of Oberlin’s most illustrious female graduates. She, Chaffee, and others roused members of the Wright Family—including some from the Wright Family Foundation who had never seen the fountain—to preserve the structure and the stories behind it. Finally, last fall, the fountain was moved to the studios of Fairplay Stonecarvers in Oberlin for restoration and repairs.

“It is truly gratifying to realize that the fountain is back. There is again something there for people to see and enjoy,” says Jim Howard, director of principal gifts at Oberlin.

During the beginning stages of the restoration process, archival images were key in determining how the fountain had been constructed. Nicholas Fairplay and his craftsmen spent eight months cleaning the marble with a pH neutral soap. Cracks were filled with an epoxy, and poultice was used to suck discoloration from the fountain’s white marble stem.

Lastly, the entire structure was sanded and polished to a smooth finish. To give the fountain proper support, a concrete base was poured and cured months in advance at the installation site. Steps that offer the words, “To Katharine Wright Haskell 1874-1929” were reinstalled. The Rosa Verona marble bowl, once a sun-bleached pink, was put in place with a crane, as was the stem that houses four of the fountain’s eight spouts. And as soon as plumbing issues are resolved, the bronze boy with dolphin will sparkle brilliantly in the sun.

As the original fountain did not allow water to recirculate, Oberlin capital funds were reserved to set up a pump system. A plan for maintaining the fountain is now in the works, as is a protective, custom cover for the winter months.

“It’s amazing how many people have come up to me and said, ‘I hear that you are doing the fountain. We used to love it!” says Fairplay. “Even in a ruined state, people loved it. It’s not just a fountain; it’s got a nice connection to Oberlin’s history.”

Oberlin’s connection to the Haskell family continues today with Oberlin graduates Judith Zernich ’72 and Tamme Haskell ’69, both granddaughters of Henry Haskell; and Morgan Zernich ’05 and Haley Zernich ’07, both great-granddaughters.

(Editor’s Note: OAM was in production when Oberlin learned of the death of Katharine Wright Chaffee ’44 on June 17, 2007. Her obituary will appear in the Fall issue.)

Top left to bottom right: Leamy, Politz, Dwyer, Ferris, Simonton, Ziegler

Top left to bottom right: Leamy, Politz, Dwyer, Ferris, Simonton, Ziegler

Spring Graduates Rack Up National Awards

May 2007 graduates Nathan Leamy and Sarah Politz were among 49 college students nationwide named to the 2007-08 class of Watson Fellows. Each receives $25,000 to pay for a year of independent study and travel outside the U.S. Leamy will travel to Mexico, India, and France to investigate the effects of the green revolution in agriculture, while Politz will spend the year traveling to Ghana, Benin, Guinea, Senegal, and South Africa to study the influence of African-American jazz and popular music on African music communities.

Cellist Paul Dwyer ’07 was one of just two music students in the country to earn a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship. The award, more than $40,000 a year for up to four years, will cover tuition and fees and provide Dwyer a stipend as he pursues a Doctorate of Musical Arts in cello performance at the University of Michigan.

The J. William Fulbright Scholarship, which awards a year of research support and travel abroad, is allowing Kristina Ferris ’07 to study in a gender, sexuality, and society graduate program at the University of Amsterdam. Lara Simonton ’07 is examining the impact of colonial and Soviet rule and Kyrgyzstan’s newfound nationhood on the Kyrgyz oral tradition in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

W. Christopher Boyd ’07 earned a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, which provides three years of support for graduate study. He is pursuing his PhD in organic chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley.

Compton Foundation Mentor Program Fellowship recipient Andrew deCoriolis ’07 will work with Bridging the Gap in Chicago to establish produce distribution centers that engage communities in food, farm, and nutrition education. The Compton supports fellows in the pursuit of a self-designed project of social merit that focuses on one of several areas, including the environment.

Shira Ziegler ’08, Oberlin’s Barry M. Goldwater Scholarship recipient, plans to continue her research in molecular genetics at Oberlin.

Projects for Peace

Sarah Bishop ’07 and Denise Jennings ’07, architects of the student group Oberlin Solidarity in El Salvador (OSES), were awarded a $10,000 grant from Kathryn Wasserman Davis’ 100 Projects for Peace. Davis, a lifelong internationalist, author, and speaker on world affairs, committed $1 million to support 100 grants of $10,000 each. Students from 76 U.S. campuses competed for the grants, which had to be used for the design and implementation of grassroots projects that promote peace. Through OSES, Bishop and Jennings planned to help mitigate a small part of El Salvador’s poverty by connecting Oberlin students with a growing number of personal and professional contacts they made in rural El Salvador during winter term.

Doctors’ Orders: 25th reunion panel offers Rx for health care

Oberlin alumni and guests spilled into the aisles of a campus lecture hall in May to hear a panel of dynamic, outspoken doctors respond to the question: “What do you view as the single greatest problem in 21st-century health care?”

The reunion weekend panel, titled “Health Care in the 21st Century: Challenges on a National and Global Scale,” was sponsored by the Class of 1982. “Each panelist has two or three minutes to rant on a topic important to them in their particular environment,” said moderator and cardiothoracic surgeon Billy Cohn ’82.

So began the wide-ranging discussion with 10 doctors, nine of them classmates from the Class of 1982, along with doctor and Oberlin Trustee Robert Frascino ’74. They responded with such compressed meaning and artfulness that it was like the lightning round of a quiz show that asked participants to answer in haiku.

“There is consensus that the health-care system is broken and needs to be overhauled,” said Heather Mullen ’82, a family physician in Cleveland specializing in women’s health. Her belief—that answers to health-care problems are likely to be found outside the industry—was echoed by nearly all of the panelists.

“Health is primarily determined by things outside the health-care environment, such as reproductive choices, smoking, and nutrition, all of which take political will to appropriately address,” said New York City Health Commissioner Thomas Frieden ’82. “We really lack a basic sense of accountability in health care. Public health-care policy can change if the political will exists.”

Frieden credits his boss, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, for pushing forward New York City’s anti-tobacco efforts, despite its potential for unpopularity. “The mayor won the election fair and square and was going to do the right thing, no matter what the politics.”

The best thing for health care? says Mullen. “Voting for campaign finance reform. The problem lies in how policy is made.” Who is elected depends upon the size of their campaign treasury,” she said.

While Big Pharma came in for a predictable thrashing, Michael Ryan ’82, associate clinical professor at the University of Washington’s department of medicine, placed some of the blame for health-care’s woes on Big Farms—or at least the big farm bill in Congress. He said the epidemic of kidney disease in America has been blamed erroneously on obesity, when “it’s really overeating. Obesity is a side effect of eating.” Ryan believes that federal subsidies doled out to farmers to grow corn and soy that turn into high-fructose syrup has helped to spur the overeating and obesity problem.

Although Frascino, president and founder of The Robert James Frascino AIDS Foundation, peppered the proceedings with lighthearted banter, his jovial demeanor gave way to a recitation of somber statistics about the continuing spread of HIV/ AIDS. “AIDS is preventable,” he concluded. “Apathy is lethal.”

Even within the realm of medicine, a wide range of views was represented.

Cohn, who opened the program with a video of a cow walking on a treadmill, said he is interested in using new technology to treat previously untreatable conditions. “New technology costs both financially and ethically,” he said. “Can we afford to do it, and can we afford not to?”

David Olson ’82, medical advisor to Doctors Without Borders, said his interest is somewhat different than Cohn’s. “I want to get available technology for treatable diseases.” Affordability, he said, is only one of the barriers to access.

The disparities in access to health care is the most troubling issue for Sarah Sutton ’82, an infectious disease physician specializing in women and HIV perinatal transmission at Northwestern University. Pediatrician Mary Lynn Bundy ’82 said that years of practice have led her to conclude that “we all want health care we can’t afford.”

For Mary Ellen Sabourin ’82, a family physician and practitioner of integrative medicine, health care in America relies too much on technology and pharmaceuticals. Instead, the emphasis should be on healing—body, mind, and spirit—using both conventional and alternative methods.

Several panelists pointed out that the health-care system isn’t designed to work when people are well. Primary care physicians don’t remind people of preventative maintenance, said Frieden. “We need to pay doctors to help people live happy, healthier, and longer lives.”

But, according to Eric Aberbach ’82, chair of the department of anesthesiology at New Jersey’s Chilton Memorial Hospital, HMOs not only don’t pay for preventative care, they do what they can to avoid paying for any treatments. “‘Any which way, they don’t pay,’ is their motto,” he said.

Similarly, the mindset of the pharmaceutical companies is on money. “They don’t judge drugs by the number of lives saved,” said Olson. When asked by a member of the audience what should be done about it, his answer was succinct: “Revolution.”

Other ideas and solutions to cure health care in America included creating cities that foster walking and bicycling; creating policies for reducing stress levels; banning ads for bad food aimed at children; making good food cost less than bad food; and making cigarettes illegal. Although some on the panel advocated a single-payer health-care system, the sentiment was not shared equally among all panelists, though it received one of the strongest ovations when first suggested by Ryan.

Class President Carol Kurtz ’82, one of the panel’s organizers, was pleased with the outcome of their efforts. “The panelists truly exceeded my expectations,” she said. “Each member exhibited professionalism, articulate thought, and great passion for the work that they do.”

Karen Checkoway reads from Slim Night of Recognition at Mindfair Books in Oberlin.

Karen Checkoway reads from Slim Night of Recognition at Mindfair Books in Oberlin.

A Poet’s Legacy

Oberlin sophomore Emma Howell was only 20 when she died unexpectedly in June of 2001. A gifted poet who’d had her first works published by age 15, she majored in creative writing at Oberlin and studied Afro-Brazilian culture and dance. At Oberlin, her poetic voice flourished.

Friend and classmate Rachael Sarto ’03 describes Emma as “emotional and complicated. She had respect for her ancestors, elders, and a gratefulness for being alive. She took those things on and lived them, while reclaiming a relationship with her own Jewish heritage and a deepening of her place in the world.”

Emma’s parents were determined to bring their daughter’s work to fruition; they combed through her old notebooks, journals, and e-mail messages, eventually selecting 38 poems for her posthumous book, Slim Night of Recognition (Eastern Washington University Press, 2007). Emma’s father, writer Christopher Howell, wrote the forward to the book.

The April launch of Slim Night was celebrated by family and friends gathered for a reading at MindFair Books in Oberlin. “It was moving to hear students read her work,” says Sarto. “It had an emotional weight with those of us who knew her, but when the students read her words, they were just poems—good poems.”

Royalties from Slim Night, which is already in its second printing, contribute to the annual Emma Howell Memorial Poetry Prize at Oberlin, which was established shortly after Emma’s death. Funds continue to be raised for an endowment in Emma’s name.

“You don’t always know if people will keep writing, but Emma, I’m sure, would have kept at it,” says book consultant Martha Collins, Oberlin’s newly retired Delaney Professor of Creative Writing. “Her surprisingly mature vision is always deep and often dark.”

“When the book arrived, it was like giving birth all over again,” says Karen Checkoway, Emma’s mother. “But this is hers, what Emma has to give to the world, just as we had Emma to give to the world.”

Gravity

My center of gravity

is the gut and gape of me

is the swallow’s pendulous

flight: empty, full, sips and gusts.Sometimes I’m too full with words

to balance the wires and birds.My mouth opens to catch air;

my body flags and fills with stars,

too heavy now, then too bright

to do anything but fly.The south wind pulls my song out,

my arms spread to steady the sound;

I float down lightly, evening

humming—the world rises: coming.—Emma Howell