Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Summer 2007 Vol. 103 No. 1

Where Are They Now?

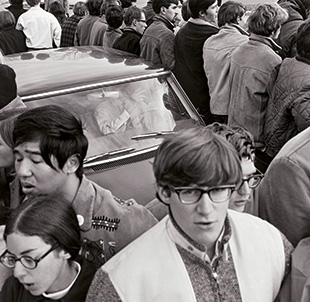

Navy Recruiter Protesters, 40 Years Later

Steve Slosberg ’69 was walking to class in October of 1967 when he came upon a throng of angry students barricading a car. The driver was a recruiter for the U.S. Navy, who had arrived on campus to interview potential officer candidates. Slosberg, in what marked his first act of public resistance, joined the growing demonstration; years later it would become one of Oberlin’s most recognized pieces of history, seen as catapulting the College into the anti-war movement.

The 40th anniversary of the “Navy Day” demonstration comes at a time when our country is again faced with a controversial war. Were the efforts of the 1960s rebels wasted? Did the protesters later regret their actions? Yes or no, the students that day stood firm in their beliefs that they were “symbolically impeding one of the important instruments of the Vietnam War.”

Slosberg, a newly retired columnist for The Day, a daily newspaper in New London, Connecticut, lives in Stonington with his wife and two children. “When I wrote about those times, I emphasized the people who showed the most courage, people like Matt Rinaldi ’69, who in his teens had gotten involved in civil rights work and voter registration in the South.”

Rinaldi, who organized with the GI movement and Teamsters for a Democratic Union after college, says, “We shared fear and danger, hope and wild optimism. We knew that a better world was possible, and we believed that change could be accomplished.” Now an attorney in Albany, California, he provides legal assistance to soldiers who want to leave the military. He and his wife have two children, Jacob ’07 and Amy ’09.

“As a child of the ’50s, I hope to be one of J. Edgar Hoover’s nightmares—a hard-core socialist who never quits,” he adds. “As an aging white guy in the 21st century, I do what I can against capitalism, racism, sexism, injustice, and war.”

Both men remember well the events of October 26, 1967, when student protesters blocked the recruiter’s car as it approached town, holding him captive on the east side of Tappan Square for nearly four hours.

Police officers tried to disperse the crowd with tear gas, smoke, and water from a fire hose. But the students held their ground, says Bernie Mayer ’68, leaving only when College administrators pledged that no recruiting would take place that day. Later, the students sang and marched their way to city hall. Some were charged with disorderly conduct and fined $50.

Recruiters were back on campus the next day. The student body was forewarned: Anyone who impeded their work would be expelled. Undeterred, protesters staged a sit-in to block the entrance of the College placement office in Peters Hall, where recruiters were to conduct interviews. Negotiations between demonstrators and administrators finally ended the sit-in, and military recruitment on campus was suspended. No one was expelled, and Oberlin held a day of reflection on the war, with presentations in Finney Chapel and group discussions on Tappan Square.

Many of the key protesters went on to graduate. And while their career paths are varied, their shared experience will keep them forever linked in the pages of Oberlin history:

Bernie Mayer ’68 was president of the Student Senate in 1967; he drove the car whose passengers spotted the recruiter on his way into Oberlin. Mayer also played a large role in negotiations with administrators, especially during the Peters Hall sit-in. “My first reaction when a couple of people broached the plan was, ‘This will never work,’ but I agreed to try,” he recalls. “The whole thing was a circus—the tear gas, the inability of the police to figure out what to do, the recruiter who was in a terrible situation. Then, in a very Oberlin moment, we agreed to let him out of the car to go to the bathroom if he promised to return. He never returned.”

Mayer went on to earn a master’s degree in social work at Columbia University and a PhD at the University of Denver. Today, as a professor at Creighton University and a mediator, conflict specialist, and partner at a nonprofit conflict resolution organization, he divides his time between Boulder, Colorado, and his home in Kingsville, Ontario, where he lives with his wife. The author of two books, he has five children and one granddaughter.

John Dove ’69 recalls vividly the tear-streaked faces of police officers who were called in from neighboring towns. He held onto one of the empty World War II-era tear-gas canisters, stamped with an expiration date of May 1954. Dove left Oberlin in 1968 to join a start-up computer software company and eventually earned a degree in mathematics. He refused to pay taxes to the IRS and the states of Massachusetts and New York until the U.S. withdrew all troops from Vietnam. Thus, in 1975, when soldiers were called home, he filed 15 returns for seven years, “gladly” paying all unpaid taxes and penalties.

Married with two sons, Dove lives in Arlington, Massachusetts, where he is the CEO of Credo Reference, an electronic publishing company. “Standing firm for what one believes in has been something that I’ve always retained,” he says. “Oberlin developed those core values. Opposing quietly but with absolute resolve the things that are contrary to one’s core beliefs is such an important thing to learn and to value. I hope I’ve passed those same values on to my children.”

“When the police marched up military style and started tossing 20-year-old tear-gas cans at us, we thought we were in Alabama or Mississippi during the Civil Rights era,” says Peter Blood-Patterson ’68, who returned his draft card but evaded jail time thanks to a sympathetic judge. Remaining committed to activism after college, he supported the Poor People’s Campaign, a nonviolent movement begun by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to address economic inequalities. He also joined the Movement for a New Society, an activist network committed to social movements and nonviolence in the 1970s and ’80s. But his biggest contribution has been a politically oriented songbook, Rise Up Singing, which has sold more than a million copies and is used by liberal churches and activists. Blood-Patterson later earned degrees in nursing and family therapy and now teaches at the University of Massachusetts School of Nursing. He and his wife live in Amherst and have two sons. “I’m very proud to have been part of one moment in Oberlin’s long tradition,” he says.

Eve Goldberg Tal ’69 remembers the sudden fear she felt as the recruiter tried to start his car while she was in front of it. She remembers the police marching toward the crowd and the sting of tear gas in her lungs. She also recalls a sense of purpose, togetherness, and power, and says she is still angry that the group allowed the recruiter to leave his car. Now an author, Tal moved to Israel after graduation where she, her husband, and their three sons live in Kibbutz Hatzor, a commune. Her first young adult book in English, Double Crossing, won several awards and will be published in paperback this fall. Her Hebrew picture book, A New Boy, has also been published in an English edition.

“When I came to Israel, I plunged into a different reality,” she says. “The police and military were no longer my enemies. My husband, a very gentle person, served in several wars, was wounded in combat, and willingly did reserve duty every year until he was almost 50. My two older sons served in army combat units. While they were growing up I was careful not to inject them with my own conflicted feelings about the military. Perhaps one of the legacies of the demonstration for me is guilt for not continuing to work for social change with the same fervor as I did in college.”

Eric Frumin ’70 helped to organize the Oberlin demonstration; he stood in the inner circle that surrounded the car. “I never forgot the tear gas, and I’m glad my kids don’t have to go through that kind of tension,” he says. “Oberlin in the ’60s was an agonizing and thrilling time.” With a master’s degree from New York University, Frumin now lives with his wife and children in Brooklyn, where for 30 years he’s served as director of occupational and environmental health and safety at the headquarters of UNITE HERE, a labor union representing textile, apparel, food-service, and hotel workers in the U.S. and Canada.

“I wish there were an anti-war movement today that believed in itself enough to do some of the same, but that was a different time,” he says. “The focus now must be on empowering ordinary people. We have to build a broad movement of ‘people-power’ against ‘corporate-power,’ one capable of enlisting widespread self-confidence, discipline, and commitment. We have no choice if we want to have a planet and a society worth leaving to our children.”

Protest organizer Charles “Chip” Hauss ’69 admits that he had proposed a slightly riskier demonstration than the one that occurred, but it was overruled, “and properly so,” he says. Hauss was assigned the task of handling relations with other students, faculty members, and the press, and his clean-cut suit led police to believe he was the ringleader. Today, he lives in Falls Church, Virginia, where he teaches political science at George Mason University and works with Search for Common Ground, an international conflict prevention and resolution NGO. He also writes books on comparative politics and conflict resolution.

“The conflict resolution work I do today is very much an outgrowth of my time at Oberlin,” says Hauss. Still, he’s apprehensive about “celebrating” the Oberlin demonstration that “happened so long ago. I am not very involved in electoral or partisan politics. No one who knows me would harbor any illusion that I voted for the president in either election. Nonetheless, because I work with conservatives almost daily, I avoid public activities that people could find insulting. I think that 9/11 and its aftermath (not Iraq) forced those of us in my line of work to find ways to collaborate with people we had traditionally thought of as adversaries.”

No one knew which route the Navy recruiter would take into town, so groups of students were positioned at all corners of campus, Robert Sheridan ’70 at North Main and East Lorain streets. Once the car became visible, his group moved on foot to form a blockade in the road. Hours into the demonstration, the recruiter became irritated, stomped on the gas, and nearly ran over several students, including Sheridan, who was thrown onto the car’s hood. “We wanted to do something dramatic, something that would make a strong statement,” he recalls.

Today, as vice president of TBA Global Events, a company that produces events for large corporations, Sheridan continues to be at the center of dramatic statements. His firm organized a rock concert at the inauguration of President George W. Bush (“It was just a job. I’m still a lifelong Democrat”), as well as for the Bristol-Myers Squibb Tour of Hope, involving Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong and other cyclists affected by cancer. Sheridan and his wife, Jennifer Thiermann ’70, have two children and live in Glenview, Illinois.

“I think back on that time with a great deal of pride. When important issues come up and I feel I must take a stand, I do so because of my experiences at Oberlin,” says Alice Slutsker Lawrence ’69, a pro-choice advocate who took part in the 2004 March for Women’s Lives in D.C. She remembers the “incredible” solidarity in “defying those who would allow Oberlin to be used as a vehicle to promote the war. The power of solidarity was intoxicating.” Living now in Oakland, California, Lawrence holds a master’s degree in teaching from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. “I have talked about those times with my daughters and have tried to instill in them the importance of activism when necessary.”

Ben Bailey ’69, who took part in several campus anti-war demonstrations, was drafted into the Navy and served four years in off-shore tours, including nine months in Vietnam. “I was miserable,” he says. “I told myself that if I ever believed what the government said after that, I’d hire a kid to kick my tail around the block.” Today, the former political science major lives in Las Vegas as a self-employed machinist and horse trainer.

Paul Osterman ’68, another of the demonstration’s organizers, is now a labor economist who teaches at the MIT Sloan School of Management, where he recently finished a four-year term as academic dean. He and his wife have two children. His research and writing deal with the impact of economic restructuring on careers, public labor-market policy, and economic inequality. He has worked with the Industrial Areas Foundation, a national network of community organizations focused on issues in poor and working-class communities. His most recent book is Gathering Power: The Future of Progressive Politics in America.

It was impossible to include everyone who took part in this event. To discuss this or other Oberlin protests, write to alum.mag@oberlin.edu.