Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Fall/Winter 2007 Vol. 103 No. 2

Letting Go

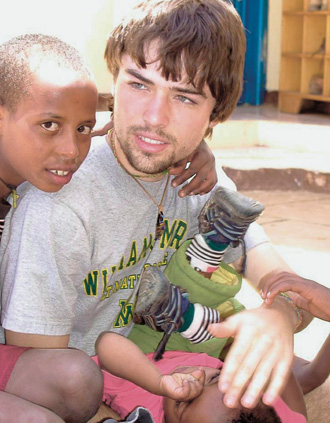

Shane O’Halloran ’10

Shane O’Halloran ’10

A parent’s perspective on a (fearless)

teen’s odyssey

The phone rang at 3 a.m. on January 16. My stomach clenched. This can’t be good news. "Mom, Dad, I’ve been robbed and I’m going to run short of money. What should I do?" It was our son, Shane, 19, calling from halfway around the world.

Publicly, we appeared cheerful and even joked about Shane’s trip. When it was just the two of us, my husband and I kept reassuring each other: "He’ll be fine; he knows how to handle himself." But privately, we weren’t so sure. Why did we say yes? What is our teenager doing in Ethiopia without a chaperone or even a professor? As parents, what were we thinking?

When Shane first broached the idea of a three-week trip to an AIDS orphanage in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, we shrugged it off as typical wide-eyed save-the-world Shane stuff.

Like loads of kids destined for Oberlin College, he’d had many advantages growing up.

He’d tried sports teams and played band instruments. On his own, he wrote poetry, strummed on the guitar, and read books by the bushel.

In high school near Philadelphia, he began to take notice of the wider world. Instead of a Philip Pullman or Brian Jacques fantasy, he reached for the Economist and the New York Times Sunday Week in Review. He joined the Mock Trial and Model UN clubs. He worked the local polls on election days. At one point, I was certain he knew more about world politics than I did.

Like many young idealists, he tried, in small ways, to give back. He gave blood. He dropped bills in the laps of every homeless person he passed.

And each summer, he repaired homes in Appalachia with the youth group from our church. His last trip, a few weeks after his high school graduation, was revelatory. The night before his return, he called us, choking back tears as he asked if he could bring back a living and, it turns out, howling souvenir: a beagle mutt who had been living under a dumpster. I said no, we already had a dog, thank you, but my husband, the softie in the family, guilted me into submission.

Lucy was an early clue that Shane would not follow the mainstream path. His college choice was another. "Nothing south of the Mason-Dixon line and no frat-boy culture" were Shane’s rules. We traipsed through 12 campuses, but in the end, he chose the only school he had visited without me: Oberlin.

When I told a Cleveland native friend about Shane’s Oberlin acceptance, she looked horrified. "That’s the most liberal school in the country!" she exclaimed. "That’s his point," I thought to myself. (Actually, in the 2008 Princeton Review rankings of colleges with "Students Most Nostalgic for Bill Clinton," Oberlin came in 10th.)

The Ethiopia idea didn’t come up until last fall, early in Shane’s sophomore year, when he was considering his winter-term possibilities for 2008. "A few of us want to work at an orphanage for kids whose parents died from HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia. Can I go?"

Uhh, say what? Without giving him an answer, we floated the idea among family and friends.

Most applauded the idea but suggested a less adventuresome destination. Safety was a recurrent concern. Ethiopia is bordered by Sudan, Somalia, and Kenya, obviously not the most peaceful of places. Wasn’t New Orleans looking for a few good men?

What if he gets sick? (For all of his egalitarian ways, Shane is an almost snobbish gourmand. If he found the food distasteful or got a bad stomach bug or dysentery, his slight, 138-pound frame might have a hard time recovering. What if he had to be airlifted out?) And how much would this adventure cost?

We shared these concerns with Shane and challenged him to answer them. In six weeks he tackled them all.

On the safety front, he presented us with U.S. State Department travel advisories and the web site and a personal letter from the Human Capital Foundation, the organization that runs the orphanage. Each vouched that the Ethiopian capital city of Addis Ababa was safe—pickpocketing and aggressive begging notwithstanding. (The Ethiopian countryside, especially near the borders, was a different story.)

He informed us that he and his cohorts (three girls, two guys) would be escorted to and from the airport to the orphanage. I’m not sure if we were relieved or alarmed at word that a government representative would check in with them each day of their three-week stay. We were also told that an adult director, a native Ethiopian, would be on the premises at all times.

To assuage our health concerns, Shane assured us that for a nominal fee, he would be covered under Oberlin’s international study abroad health insurance plan, which would pay for those dreaded medical evacuations and parents’ visits to bedsides in far-flung hospitals. He also submitted to a visit with a gastroenterologist and lab tests to rule out a medical basis for his overly slight build. And he tracked down the appropriate clinics and happily rolled up his sleeves for a series of exotic immunizations.

Costs, we were assured, would be minimal. The group would negotiate cut-rate round-trip flights and would stay for free in the office/guest house of the orphanage, which was equipped with a kitchen and a computer with Internet access. (We didn’t learn until later that the kitchen consisted of a refrigerator and sink into which water ran only sporadically and the dial-up Internet didn’t work at all.)

With our objections answered and a needed winter-term credit for Shane in the offing, we had been worn down.

He would fly to Ethiopia on January 12.

At the beginning, things were touch and go.

We dropped him at Dulles International Airport and foolishly told him to text-message or e-mail us when he arrived in Africa the next night. We waited for three days to hear from him. At last, we received this e-mail:

Sorry this e-mail has been so delayed—yesterday the Internet cafe was closed, and I have no cell phone service at all. We’re in safely and settled into the guest house ... The orphans are all incredibly happy and vivacious and love meeting new people. Yesterday two kids told me they loved me, and everyone gives tons of hugs. I’m slowly picking up some rudimentary Amharic phrases which have been helpful. Addis is HUGE, dusty, and poor. Everyone on the street stares at us. I’ve only seen two white people aside from our group since I’ve been here, and that includes our trip to the embassy to register. Most are friendly and helpful though. I’ve determined I don’t really like injera, which is the crepe-consistency dish that makes up the base of almost all traditional cuisine, but there are plenty of western options in the restaurants. Food is SO CHEAP—as in about a dollar an entree!

The next night we received the middle-of-the-night phone call. About $120 was taken from his backpack in the guesthouse. Shane ended up borrowing money from a fellow volunteer to tide him over. With no ATMs, procuring cash (usually from a Visa debit card) was always an adventure. For a few days, he had no money at all. We never spoke by phone again but corresponded by e-mail via internet cafe. A few excerpts:

We’re doing fine over here, spending our mornings mostly relaxing and cooking, and afternoons and evenings with the kids. (With the occasional late-night pit stop at the Central Bar and Restaurant.)

This weekend was the festival of Temket, the Ethiopian Orthodox Epiphany. On Saturday we attended a really interesting church service, where everyone wore white and we listened to a roughly 45-minute sermon in Amharic. Yesterday we ventured into the city to watch the grand procession (Don’t worry Mom, I got tons of pictures.)

The coffee ceremony, as they call it, is also very nice—the beans are roasted and then ground in front of you, then you sit through three cups of espresso-strength stuff. After that, it isn’t as tiring to act as a human jungle gym to the orphans.

Two days ago, I had to stay in bed because I felt very sick—(I think I might have screwed up on the no local water directive somehow.) I made a quick enough recovery to be able to come out to dinner that night though. We went to the Zebra Grille, with the motto "Good food Good mood," and it actually lived up. I had delicious Lamb Kebobs and fries.

And finally:

I was wondering how you would feel about sponsoring a kid here named Seyfe as my birthday present. It’s $360 a year, but this kid is so incredible and doesn’t yet have a sponsor as most of the others do. He’s also blind in one eye, and I’m looking into a fundraiser to pay for his surgery, since as it stands now, he can’t attend school because he can’t see the blackboard. He’s on the quiet side but you can just feel the happiness radiating from him when he receives love. He’s very dark for an Ethiopian, thin, devoutly religious. (He came to Selamta from a monastery where he was helping the priests, where he incurred his eye injury from a burning ember), loves my necklace and his whistle, and tries to keep up in soccer despite his handicap.

We agreed to sponsor Seyfe, somewhat relieved that international adoption rules were such that Shane couldn’t sneak him home on his lap, Lucy-style.

Jetlagged and, no doubt, skinnier than ever, our son returned directly to Oberlin in one piece in early February. (The handcrafted Ethiopian coffee ceremony tray, alas, did not.) It didn’t take him long to dive back into the scholastic soup of sophomore year, but I fear Africa has stolen his heart. I too have been turned on to all things African—La Colombe’s new Afrique coffee, the Pennsylvania-based Echoes Foundation that assists kids in Uganda, Dave Eggers’ sensational novel What is the What?

Shane is already talking about a return trip to Addis Ababa next year, and my husband talks about joining him. As for me, I was more than satisfied with my son’s bone-crushing hug when he came home for spring break.

Adapted from an article that appeared in Main Line Life, where Caroline O’Halloran is the Lifestyles editor.