Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Summer 2009 Vol. 104 No. 4

Q & A

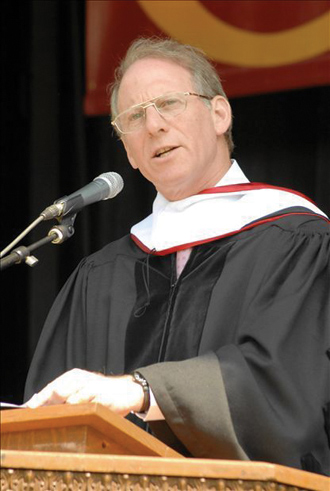

(photo by Kyle Dick)

(photo by Kyle Dick)

Richard Haass ’73 answers a few questions from Helen Hare ’09

Graduating senior and Truman scholar Helen Hare spoke with Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, a few days before he delivered the Commencement address at her graduation ceremony. They discussed Haass’ latest book, War of Necessity, War of Choice, in which Haass characterizes the 1990-91 Gulf War as a war of necessity and the ongoing war in Iraq, begun in 2003, as a war of choice. Haass was a member of the National Security Council staff under President George H.W. Bush and director of policy planning in the State Department for President George W. Bush.

What is the most important distinction between a war of choice and a war of necessity?

One is that wars of necessity tend to involve the most critical national interests, whereas wars of choice involve lesser interests. Secondly, wars of necessity come about when you have no viable alternatives to using force, whereas in wars of choice, there are viable policy alternatives.

In your distinction, where do humanitarian motives fall? Can responding to genocide in another country constitute a war of necessity?

Those would be wars of choice for the United States. We made just that choice in Bosnia and Kosovo, but did not in Rwanda or Darfur.

You say wars are fought three times: the political struggle to justify the war, the physical war, and the war of interpretation. How is the second Iraq war being interpreted now?

Quite negatively. This is mostly because of how it was done, but also to some extent because we learned there were no WMDs [weapons of mass destruction]. The current judgment is quite harsh. It will be interesting to see how history deals with it, though. To some extent it may depend on how things turn out. I expect that one historical school will say it was a bad choice and badly implemented. Another school may say the war was a good choice but badly implemented. The debate will be about whether things could have turned out differently had it been done better or had we gone about the aftermath better.

The 1991 Senate vote authorizing the Gulf War was close—52 to 47. If the first war in Iraq was a war of necessity, why didn’t more senators recognize that necessity?

Great question. I don’t have an answer. I assume it may have had something to do with politics. Certainly there was greater domestic support for the second war, although, again, politics may be the explanation.

Why did you believe that there was a high probability that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction?

Every piece of intelligence, every analysis suggested that he had WMDs. Nobody, in my experience, made the opposite case. I also think there was an assumption that people made—an assumption that he had them—and that became the lens through which people saw every new piece of information. This biases you. Assumptions become distorting filters. That’s what happened.

Were you troubled by the attempts to link 9-11 to Iraq?

I was. Look at it this way: I don’t mind that people asked the question of whether there was a link. I was troubled that people persisted despite a lack of evidence. Any time you have to work that hard at something, it suggests to me that there is an obvious political motive. And I never saw anything that made even a flimsy case.

You suggest that it may be difficult to mobilize support and resources for wars of necessity after we fight wars of choice. If there is a need to go to war in the next few years, will the unpopular second Iraq war make it difficult to mobilize support? Is this one of the costs of waging a war of choice?

It will certainly make it more difficult to do other costly wars of choice. We may have a test of that in Afghanistan. I expect within another year or two we will have a debate about Afghanistan and a debate about Iran. My guess is that during Barack Obama’s presidency we are going to have several heated debates about whether to go to war.