Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Summer 2011 Vol. 106 No. 3

’

PERSPECTIVE: Should we care about rankings?

U.S. News & World Report published its first rankings of U.S. colleges in 1983. In that issue, Oberlin was ranked fifth among the nation’s top liberal arts colleges. Back then, to determine a college’s ranking, U.S. News did a simple thing: it merely asked other college presidents what they thought about their competitors. Considering Oberlin’s long history as one of the world’s best liberal arts colleges, the result was hardly a surprise.

For a few years, Oberlin held its position in the rankings. In 1987, it still ranked fifth. But in 1988, Oberlin fell out of the top 10, and in the 2011 rankings placed 23rd.

How should we interpret this trend in Oberlin’s U.S. News rankings? Is Oberlin no longer as good as it once was? Or did its reputation change among college leaders even while its quality and performance remained relatively unchanged—or even improved?

More importantly, how much weight should we give to the rankings? Should we even consider them at all?

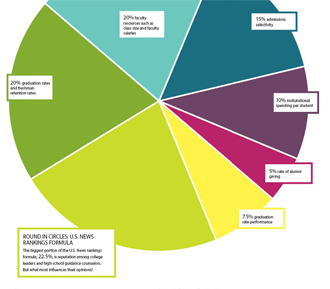

In 1988, U.S. News began using a more objective formula to determine its college rankings. This formula still weights a reputation survey of college leaders (and new this year, high school counselors) most heavily (22.5 percent). But the formula now also considers graduation rates and freshman retention rates (20 percent), faculty resources such as class size and faculty salaries (20 percent), admissions selectivity (15 percent), institutional spending per student (10 percent), and the rate of alumni giving (5 percent). It also tries to measure value added by predicting a graduation rate based on selectivity and the proportion of low-income students, and including the difference in its formula (7.5 percent).

This formula marked the beginning of Oberlin’s decline in the rankings in the late 1980s. Many of the indicators selected by U.S. News were unfavorable to Oberlin’s size and strengths. For example, including institutional spending per student is less favorable because Oberlin, at nearly 3,000 students, is approximately twice as large as Swarthmore and Amherst. Including the admissions rate is also less favorable, because although Oberlin receives more applications than Carleton and Grinnell, it has many more places to fill in its incoming class.

Interestingly, many of Oberlin’s indicators have improved substantially over the years. From 1999 to 2006, the acceptance rate fell from 54 percent to 34 percent, and the percentage of students in the top 10 percent of their high school class rose from 54 percent to 68 percent. The SAT score of students in the 25th percentile rose by 70 points. These positive moves were largely mitigated, however, by similar increases at the other top 25 liberal arts colleges. The increasing size of the U.S. college-going cohort, the increasing competitiveness of top high school students, and the maturation of the national college market have all been important factors in improving the academic profile of elite colleges.

The most important factor in the change of a college’s reputation wasn’t changes in its financial performance, the academic markers of its incoming class, or the quality of its instruction.

But the strange part is what happened to Oberlin’s reputation among other college presidents and provosts. Over the course of the 1990s, Oberlin’s reputation score—the average of a 1 to 5 rating provided by all the survey responses—fell in each successive year. So while Oberlin substantially improved the academic accomplishments of its incoming students, the college’s reputation among its peers declined. Did college presidents have some insider information about a change in Oberlin’s quality? Were they looking more carefully at the indicators of Oberlin’s performance and judging accordingly? And what about the other liberal arts colleges and research universities—can we ascertain a similar pattern?

A few years ago, I decided to investigate this question with Nicholas Bowman, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Notre Dame. We wanted to see if we could figure out what led to increases or decreases in a college’s reputation score. For example, were people looking at the admissions and financial indicators that U.S. News uses to calculate its formula? Or were other forces at work?

To look at this question, we entered the published rankings data for the top 25 liberal arts colleges and research universities, both in 1989, the first year that all the data was available, and in 2006, then the most recent data available. After controlling for the important factors, we came to a startling conclusion. The most important factor in the change of a college’s reputation among peers wasn’t changes in its financial performance, the academic markers of its incoming class, or the quality of its instruction. It was the ranking itself.

This result turns our thinking about rankings on its head. The creators of rankings ask people about reputation because they want to include it as an independent indicator of a college’s quality. They think academic experts know more about peer institutions than may be observed in mere numbers, and thus a college’s reputation should help shape the trajectory of its ranking. But the exact opposite is true; the ranking shapes the trajectory of a college’s reputation, to the point where rankings and reputation are no longer independent concepts. To put it simply, the ranking of a college has become its reputation among other college leaders—the same leaders who bemoan the influence of college rankings.

We found a similar result when we looked at the global rankings of universities from around the world, which are published by Times Higher Education, a magazine from the Times of London. Before the rankings were published, if you asked a higher education expert to compare the quality of the University of Sao Paolo to the National University of Singapore, few if anyone could tell you anything of interest. It was virtually impossible: these are universities in two completely different national systems, with different goals and objectives, which do not seek to compete with one another. It would be hard to find someone who had even set foot on both campuses.

Undoubtedly, a new set of global rankings would fill the information vacuum. So when the first global rankings were published by the Times, the results were widely read around the world, particularly among government leaders interested in how their systems compared. Suddenly they had an answer, neatly contained in a single table of the top 200 universities in the world. Unsurprisingly, the United States did very well on the list, taking the majority of places in the top 10.

Nick Bowman and I were very interested to see what effect this list would have on subsequent surveys of university reputation. In the 1970s, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman did groundbreaking work (that ultimately won the Nobel Prize) on a concept they labeled the "anchoring-and-adjustment heuristic." Tversky and Kahneman conducted an experiment. They took a wheel with a random set of numbers and spun it in front of random subjects one at a time. After a number came up, they asked the subject a simple question: How many nations are in Africa?

Then they looked at the data and found an amazing result: the number of African countries named by their subjects was much closer to the random number spun on the wheel than would be expected by chance. They proved that even an entirely arbitrary number could have a significant influence on later numerical judgments made by people about completely different things. The arbitrary number was an anchor, and people adjusted their thinking accordingly. Nick and I thought we might see the same principle operating in our data.

Just like we did with U.S. News, we took the Times rankings data for the 200 top universities and tracked the results over time. In the first ranking, there were often big differences between a university’s reputation score and the ranking it received from Times Higher Education. In each subsequent year, the difference between one year’s ranking and the next year’s reputation score became less and less. Suddenly there was a clear consensus on a university’s reputation, be it Sao Paolo or Singapore. Where once there was ambiguity, now there was certainty.

But this does not yet answer the question: How much do rankings matter? There are many problems with rankings—the problems we identified in reputation being high among them—but that does not mean they don’t have significant effects on college administrators, alumni, students, parents, and policymakers (in short, everyone who has influence over the future of a college, Oberlin included).

It turns out that the influence on students is fairly weak. Every year, first-year college students are surveyed about their attitudes and opinions by the Higher Education Research Institute at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). In 2006, the researchers found that only 16 percent of students reported that rankings had had a strong impact on their decision. Nearly half of all students said that rankings were not important to them at all.

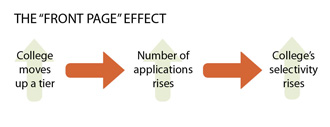

But these are only self-reports about students’ beliefs—what about their actual decisions? Nick and I decided to test this too. Looking at all the admissions data for national research universities from 1998 to 2005, we found that there was a substantial boost for colleges when they moved from one tier to another, either up or down. When they went up a tier, the number of applications went up, and with it, the college’s selectivity. (We called this "the front page effect.") But going up just a few places in the numerical ranking had only a very small effect for national research universities.

And we found no admissions effect for liberal arts colleges at all. In fact, the strongest influence we found on admissions to liberal arts colleges was tuition price, and the effect was positive! That is, the higher the increase in tuition, the better the admissions results looked the following year—part of a phenomenon often dubbed "the Chivas Regal effect."

Rankings often become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If the effects on students are weak, what about other entities that provide funds to higher education, like foundations, industry, states, and federal government research programs? It turns out the effects here are also fairly minimal, and only apply to certain providers. When the funder is from within higher education, we see that increases in ranking do have a positive effect. For example, a college’s alumni seem more likely to donate, and out-of-state students are more likely to enroll and pay higher tuition. The university faculty making decisions on federal research applications seem to be similarly affected.

But when the funder is from outside of higher education, such as private foundations, industry, or state governments, these funders seem relatively impervious to changes in a college’s ranking. Certainly foundations and industry, much like students and alumni, appear inclined to fund the more prestigious over the less prestigious. But they don’t follow changes in ranking from year to year like those in higher education do.

This result is fairly ironic. College rankings are designed primarily to provide information about colleges to people outside the higher education system. Yet the only people strongly influenced by them are those within the higher education system—college presidents, students, faculty, and the college’s own alumni.

Unfortunately, this is not the message that has been received by college administrators around the country. For many college leaders, magazine rankings are a major form of accountability. When the rankings go up, there is ample opportunity for celebration, press releases, and kudos. When the rankings go down, there are recriminations and demands for changes that will improve colleges on exactly the kind of indicators that U.S. News chooses to measure.

The result is that rankings often become a self-fulfilling prophecy. As sociologists Wendy Espeland and Michael Sauder have argued, based on interviews with more than 160 business and law school administrators, people naturally change their behavior in response to being measured and held accountable by others. In addition, they tend to be disciplined by these measures, in that they take on the values of those who are measuring them. It doesn’t matter if the effects of rankings are real, because self-fulfilling prophecies are the result of a false belief made true by subsequent actions. In our case, we were able to demonstrate that this belief influenced administrators’ beliefs about college reputation, which gave the rankings even more power than they had initially.

The dark side of these self-fulfilling prophecies is the strong incentive to manipulate the data provided to calculate rankings. As sociologists Kim Elsbach and Roderick Kramer found with business schools, rankings that are inconsistent with a college’s self-perception often lead to conflicts over mission, goals, and identity. This can lead colleges to try to bring the external ranking back in line with their self-perception—by any means necessary.

In recent years, we have seen numerous examples of rankings manipulation in the press. Catherine Watt, a former administrator at Clemson University, revealed at a conference that senior officials there sought to engineer each statistic used by U.S. News to rate the university, pouring substantial funds into the effort. She also revealed that senior leaders manipulated their U.S. News reputation surveys to improve Clemson’s position. Inside Higher Ed, an online magazine for college leaders, later showed that Clemson president James F. Barker had rated Clemson (and only Clemson) in the highest category, and rated all other colleges in lower categories.

The Gainesville Sun subsequently used a Freedom of Information Act request to discover the ratings provided by public college presidents in that state. These papers showed that University of Florida president Bernard Machen had named his university equivalent to Harvard and Princeton, and rated all other Florida public colleges in the second-lowest category. It is unclear how systematic this manipulation is, because U.S. News refuses to release even redacted copies of the surveys, and will not say how many surveys are not counted due to evidence of tampering.

We have seen that rankings will matter for as long as college administrators continue to believe they matter. Where does that leave the future of college rankings? Certainly it would be foolish to imagine they will disappear anytime soon. In fact, evidence shows that rankings have become steadily more powerful over time among selective colleges. And within law and business schools, the influence of rankings borders on mania.

One positive development is the proliferation of rankings from a variety of sources. Washington Monthly tries to rate colleges on their values, by looking at the percentage of students who qualify for Pell Grants and join the Peace Corps. Yahoo! has rated colleges based on the quality and pervasiveness of their technology. The Advocate ranks schools on their quality of life for LGBT students. Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings competes in a global marketplace of rankings with Jiao Tong University in Shanghai and a new effort coordinated by the German government. Ultimately, this may have the effect of both increasing the fit between a student’s needs and the ranking they seek for information, and improving the quality of rankings information as each ranking competes for dominance.

Even U.S. News increasingly differentiates its rankings. We focused on the national research universities and liberal arts colleges, but they provide rankings in all kinds of categories, so that one can be the top "master’s comprehensive university in the Southeast" or the top "public liberal arts college in the West." This differentiation could allow colleges to choose where they compete and on what basis, providing somewhat more flexibility in their choices.

But I hope that solid evidence—provided by my own research as well as by many others—will ultimately convince administrators, trustees, and alumni to turn down the volume on college rankings. Rankings are simply pieces of information provided by sources with particular goals and agendas. Everyone acknowledges that they are flawed. It is crucial for colleges to keep rankings in perspective and not lose sight of their most important values.

Ultimately, rankings do not measure the things that really matter in a college experience. Rankings will never tell us how high the quality of Oberlin’s teaching is, how committed Oberlin’s professors are to undergraduate education, and how much value Oberlin students will gain from their college experience. Rankings will never help us understand how Oberlin graduates use their education to influence public policy or change the world through their entrepreneurial endeavors. And there is nothing in the existing research to suggest that Oberlin would benefit substantially from changes whose only effect would be to improve its ranking.

This is the lesson for Oberlin. Oberlin could increase its ranking by cutting its enrollment, manipulating its admissions statistics, and sending glossy propaganda nationwide to those who complete the reputation surveys. Or Oberlin could continue to focus on the things that are truly important, like improving graduation and retention rates, engaging alumni, and focusing resources on the student experience. This could improve rankings too, of course, but only as a side benefit to reaching Oberlin’s true potential.

Michael Bastedo ’94 is an associate professor at the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education at University of Michigan. His research is available at www.umich.edu/~bastedo.