Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Summer 2012 Vol. 107 No. 3

Memories of a Movement

Oberlin Alumni reflect on their time in the civil rights movement of the early 1960s.

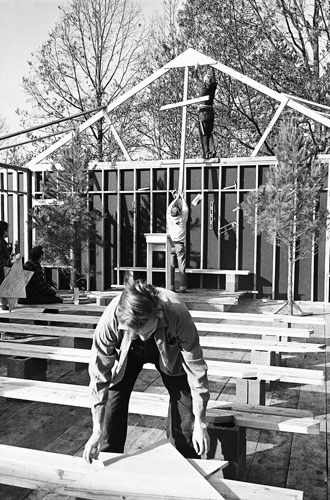

Oberlin's volunteer Carpenters for Christmas helped rebuild the Antioch Baptist Church in Ripley, Mississippi, in 1964. The church had been destroyed after a civil rights rally was held there. (AP Photo/Bill Hudson)

Oberlin's volunteer Carpenters for Christmas helped rebuild the Antioch Baptist Church in Ripley, Mississippi, in 1964. The church had been destroyed after a civil rights rally was held there. (AP Photo/Bill Hudson)Although some of the civil rights movement's most important actions and crucial legal victories took place in the 1950s, it was not until the dawn of the new decade that the movement took hold of Oberlin and other northern campuses.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) had officially overturned state-sponsored segregation in public schools, and the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott had led to the desegregation of public transportation in Alabama, yet an atmosphere of fear, violence, and intimidation still pervaded day-to-day life for African Americans living in the South under the Jim Crow laws and customs.

For the Oberlin campus, which was overwhelmingly white, these struggles seemed worlds apart from the small Ohio college town that prided itself on equality and racial justice.

Most of us knew something of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and what Martin Luther King Jr. had done," says Roger Buffett '61. "But most of us were northerners, and many had never seen 'Whites Only' signs except in Life magazine photographs. Somehow much of what was going on elsewhere on the racial front did not seem immediate to many of our lives in 1957."

That changed on February 1, 1960, when four students from the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina sat down at a whites-only lunch counter at a Woolworths in Greensboro. The students were denied service, but returned the next day, when more than 20 others joined them at the counter, followed by hundreds in the subsequent weeks. The action attracted the attention of students across the country, and Oberlin became one of many campuses gripped by the excitement of the burgeoning student sit-in movement.

That spring, Oberlin students led fundraising drives, solidarity marches, and pickets outside Woolworths and other drugstore five-and-dimes in Youngstown and Cleveland. "I had been supporting the civil rights movement and its activists mentally and morally since first becoming aware of injustice and racism in our society," says Margaret Roberts Camp '63, who recalls hitchhiking to Youngstown to picket a five-and-dime her freshman year. "But until that day, I had only read and discussed it. Now I was proud to walk the length of that sidewalk, back and forth, holding up a sign declaring my solidarity."

The sit-in movement coincided with the presidential election and with Oberlin's mock political convention, a century-old campus tradition at which real issues were discussed, and to which national figures were invited to speak. At both the real Democratic convention and Oberlin's parallel one, the sit-ins were a major topic of discussion, with Southern delegates aggressively lobbying against the strong civil rights plank. "We had a parade, and our float had two outhouses: one that said 'For Whites Only' and one that said 'For Blacks Only,'" remembers Pete Guest '63, who chaired the Arkansas delegation at Oberlin's mock convention. "So we kind of made light of it, too."

Back in the real world, Oberlin was receiving daily dispatches from Fisk University in Nashville, where Pat Hasegawa Masumoto '61, a junior on an exchange program there, had stumbled onto the burgeoning movement. While in Nashville, Masumoto had attended a student-led workshop in Gandhian nonviolence, which prompted her first sit-in.

The movement spread, Masumoto recalls, "like wildfire. In the early beginning, nobody knew what was going to happen next, so everyone just jumped in and taught each other 24/7—at the campus, the dormitories, the coffee shops," she says. "Every day [at Fisk] you'd walk into a situation and learn something. That was the beauty of it. It was a communal experience."

So I said to [my friend], 'What is this? You're asked 'what's going on?' and the answer is 'you.' And he said, 'It's simple. In order to know what's happening, you have to be what's happening.'"Despite bomb threats that led to campus lockdowns and thus curtailed contact with the outside world, Masumoto communicated with Oberlin as a de facto Review correspondent via daily phone calls and telegrams. To students like David Finke '63, a freshman at the time, these regular updates were nothing less than calls to social action.

"There was this feeling of intimacy, of making connections with what was happening, with this daily excitement coming out of Nashville," he says. "We were getting these daily dispatches, and there was this sense of immediacy, of partnership, of political engagement and relevance. This wasn't book learning. This was happening right now."

By May 1960, several Nashville restaurants had agreed to desegregate their lunch counters, leading to a brief lull in local sit-in activity, but the sit-in movement still spread to college towns throughout the South.

Jeff Piker '62 attended Fisk as an exchange student the semester after Masumoto did. "The common greeting students used when they met each other was 'What's happening?' or 'What's going on?'" he says. "Only they didn't say it that way: they said ''s'happening?' or ''s'going on?' And the answer was: Jeff Piker '62'You, Mama', or 'You, Daddy'. And so I said to [my friend], 'What is this? You're asked 'what's going on?' and the answer is 'you.' And he said, 'It's simple. In order to know what's happening, you have to be what's happening.'"

Thanks to student dispatches from the South and extensive national media coverage, Oberlin students knew what was happening in the struggle for racial equality. Now, it was their responsibility to figure out how to be it.

Down to Mississippi

Andrew Maguire '60, then a senior working for Kennedy's presidential campaign in Washington, D.C., heard that the King-led Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was issuing a call for a youth leadership meeting at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. It was at this meeting that the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was formed.

Maguire attended as an informal student representative, covering the event for the Oberlin Review. One of only a handful of northern delegates, he was thrilled to be in the presence of renowned figures like James Lawson '57, whohad left Oberlin's Graduate School of Theology to become a leader in the movement. "There was an absolutely incredible sense of making history with the people that were there, even at the time it was happening," he remembers.

Emboldened by this crash course in civil disobedience, Maguire volunteered to put nonviolent tactics into practice by joining a picket line outside Woolworths. When a white passerby hurled epithets at him and punched him in the jaw, Maguire resisted the urge to fight back.

Oberlin Review reports from the front lines of the struggle, like those by Masumoto and Maguire, strengthened students' curiosity about the movement. "If you were a rational, empathetic human being, you had to develop some level of concern for the issue," Guest says.

A steady stream of guest speakers from SNCC, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the SCLC, and the Urban League visited campus. Fundraising campaigns were held, and campus-wide open forums called Arch 7s (held at 7 p.m. at the Memorial Arch) often discussed civil rights. In the spring of 1961, one well-attended protest was called to demonstrate support for the Freedom Riders, many of whom, including Williard "Bill" Svanoe '59, had been thrown into the infamous Mississippi state prison, Parchman Farm, for attempting to desegregate interstate bus transit.

"Starting with the sit-ins, the heavy hand of the Eisenhower years—the political repression, the studied student apathy, caring only about oneself, one's career, one's social life—it's like it was shattered and blown away, and we had a completely fresh start," recalls Finke, who worked on voter registration in Tennessee. "That momentum carried on through the decade."

"I think it's important for young people today to understand how much power there is in not knowing what you can't do."

Despite the high concentration of civil rights-related activity on campus, many students felt isolated from the hub of movement activity down south, a sentiment captured in a November 17, 1961, Review editorial: "Events unroll far away, and it seems that concerned students on isolated northern campuses like this one can do little more than empathize and face the frustration which grows out of attending the civil rights Arch 7s, saying the civil rights slogans, and not being able to take a direct part in the solution of this problem."

It was that sentiment that drew an increasing number of student activists to the South. Many students enrolled in Oberlin's exchange programs with southern schools, like Fisk and Hampton University in Virginia, and an additional exchange program was established with Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi. Others took leaves of absence to participate in sit-ins, protests, student conferences, and voter registration efforts. A few, like Paul Potter '61, got brutally beaten for their efforts.

Charlie Butts '67

Gilbert Moses '64 and Charlie Butts '67 were among those who put Oberlin on hold to join the movement full time. While attending an SNCC conference, the freshmen heard about a group of sharecroppers in Fayette County, Tennessee, who had been evicted for registering to vote in the primary election. Faced with the loss of their homes and their livelihoods, these farmers had set up makeshift tent cities throughout the county.

Over Christmas break, Moses and Butts traveled to Fayette County to volunteer with a grassroots organization aiding the sharecroppers. They were shocked by what they saw.

"In Fayette County I would often hear about lynchings months after they occurred," Butts says. "You'd think someone would have had to pay for that, or answer to some kind of authority, but of course that's not the way it was in the South. If you talked about it, then you might end up being killed as well. I had read about this and knew about it before I went there, but to really understand that people actually lived that way was astonishing."

Moses eventually left Oberlin to join SNCC in Jackson, where he cofounded the Mississippi-based all-black theater company, Free Southern Theater. Butts remained enrolled and launched an aggressive fundraising campaign to build homes for the evicted sharecroppers and help them plant their crops. Over the next few months, he traveled to campuses across the country, bringing attention to the sharecroppers' plight and raising funds. He eventually procured a $9,000 loan from an acquaintance in New York before returning to Fayette County, where he lived for more than a year and a half.

Next Stop: Parchman Farm

Bill Svanoe '59 was one of hundreds of participants in the 1961 Freedom Rides, which aimed to test the 1960 Supreme Court ruling against segregated interstate transportation. Organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and SNCC, the Freedom Rides sent dozens of integrated groups of travelers on Greyhound and Trailways buses to various southern cities; many of them were beaten or jailed for their efforts.

"We were making [the South] pay a huge price, both in terms of the negative publicity surrounding their segregationist policies, and to make them pay the cost of incarcerating us," Svanoe says. He had just finished grad school and was living in New York when he first heard about the Freedom Rides.

"When I was at Oberlin, I was very much involved in the folk music scene, so I was familiar with Jim Crow, but I'd never seen it firsthand," he says. "Then during my last year, I saw Dr. King speak, and I realized at that moment that this was not the country I thought it was." He and a fellow Oberlin graduate decided to go to the CORE office in New York and sign up.

After demonstrating their understanding of the risks involved with the trip, Svanoe and his friend were told to go home and wait for their call. A few days before their scheduled trip to Atlanta for nonviolence training, Svanoe's friend called, saying that his wife had convinced him not to go. When Svanoe boarded the bus to Georgia, he did so alone.

"They [CORE] were very clear about the risks involved," he remembers. "So I was scared, sure. But I also just felt it was the right thing to do."

In Atlanta, Svanoe and 15 other Freedom Riders participated in a three-day crash course in the history of nonviolence and training in peaceful protest tactics. "They told us if you got into a situation that looked like it could be violent, you should fold up like a crab, put your head down, cover your head with your hands, and make sure that the soft spot of your head was covered," he recalls. "Details like that would let them know immediately that you were nonviolent."

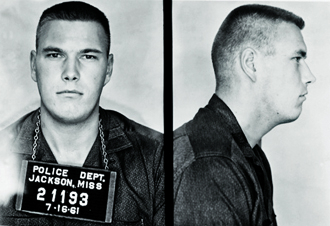

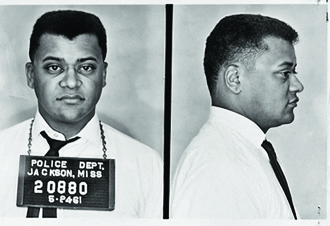

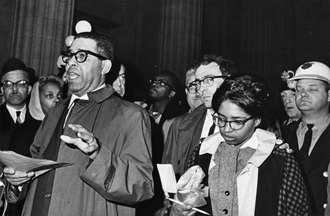

Bill Svanoe '59 (top photo) joined the Freedom Rides that James Lawson '58 (pictured here) helped organize.

Bill Svanoe '59 (top photo) joined the Freedom Rides that James Lawson '58 (pictured here) helped organize.On July 16, 1961, Svanoe's group boarded the bus to Jackson, where they were to sit down at the "colored only" lunch counter and ask to be served. From the very beginning, the plan went less than smoothly: although they were supposed to be traveling incognito, one of the riders revealed to his seatmates that he was on a Freedom Ride, and the word quickly spread among the passengers. Svanoe's seatmate, an irate, "drunk, ex-Marine type," put a gun to his head, which almost started a bus-wide riot hours before the Riders had even crossed Mississippi state lines.

When the group pulled into the Jackson bus station, a police task force had already arrived, flanked by mobs of angry Mississippians. Svanoe and the other Riders were arrested, taken to the county court, and sentenced to six months in jail. They were then driven three and a half hours to the notorious Parchman Farm in Yazoo City, Mississippi, where the men were stripped down naked and threatened with cattle prods.

"They would just endlessly try to intimidate you by trying to make you as uncomfortable as possible, or try to bait you by trying to get you to argue with them by saying things like, 'Why do you want to integrate? They [blacks] are just going to come out and rape your women,'" Svanoe remembers. "But we were instructed not to say anything, so we didn't. Which was very difficult."

Svanoe and another Freedom Rider were assigned to a 6x9-foot cell on Death Row. "There were two metal bunk beds with sharp metal edges and slots the size of a half dollar. The guards did things like take the mattresses off the bunk beds, so you couldn't sleep for more than 15 minutes because the holes would dig into your skin," he remembers. It was summer, and the Delta heat was brutal; it also brought "huge, creepy-crawly bugs," which fell out of the ceiling onto the inmates while they slept.

After a while, Svanoe and his cellmate were moved to a larger cell with 35 other inmates, with bunk beds in the center and a communal toilet and shower in the corner. They were instructed not to walk around the room at night, because there were guards around the perimeter at all times who would shoot if they saw a hand or face near the windows. "We didn't know if that was true, but no one was going to test it," Svanoe says.

The prisoners passed the time by singing folk songs and playing with a makeshift Monopoly set made from a sheet and pieces of bread. One evening's entertainment consisted of an inmate reciting his entire PhD thesis.

Every few weeks, new Freedom Riders would arrive with news from the outside world. "It was the summer that the Berlin wall went up, and the summer that Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris were going for the home run race, so there was a lot of news," Svanoe recalls. "And this guy came in who'd smuggled in parts of a radio by taping them behind his balls. When he got there, he put this little crystal radio together, so we'd quietly huddle in a corner together and have a news hour."

Despite the welcome diversions from the new arrivals, Svanoe found it difficult to stave off feelings of depression and anxiety, especially in the days leading up to his anticipated release. "When you're in a situation where you're making no decisions for seven weeks, and there's nothing you can do, it's kind of a mental exercise to keep yourself from feeling helpless," he says. He was also concerned that CORE would forget to spring for his bail. More and more Freedom Riders were coming in every day; if no one at CORE remembered to bail him out, Svanoe would be faced with the daunting prospect of serving his full, six-month prison term.

Svanoe was released at the end of his seven-week sentence and returned to New York City shortly after. In the years to come, he formed a #1 hit singing group (the early 1960s folk group the Rooftop Singers, known for its version of "Walk Right In"), which helped integrate a Tennessee theater while the group was on tour; he is now a screenwriter, playwright, and dramatic writing professor at UNC Chapel Hill, though he says he has no plans to memorialize his experiences on the page anytime soon.

"I can't think of a way that could've done it justice and been accurate," he admits. "And I felt that the things that have happened since then—and of course, the fact that we have an African American president now—as far as I'm concerned, you don't need the story. That's all that needs to be said."

During this time, the Oberlin Review meticulously covered Butts' efforts, and the NAACP supported his work by holding a fundraising drive in a "tent city" set up in Tappan Square. A number of Oberlin students joined him to volunteer in Fayette County for a few weeks at a time. Butts would later recruit even more students, including Delbert Spurlock '63 and Michael Lipsky '61, after taking the helm of the Jackson-based civil rights newspaper the Mississippi Free Press.

Butts was 18 when he first traveled to Tennessee in 1960—not yet old enough to vote; he would not return to Oberlin until the mid-1960s, receiving his degree in 1967. Like many student activists, he considers his time down south as an education in itself.

"A lot of people whom I worked with down south not only had energy, but tremendous courage and creativity and wonderful imagination and perseverance in the face of these constant challenges: how to get another couple of dollars to keep going, how to convince an older gentleman who was not able to read get excited enough that he would walk right by the sheriff at the registration place in the county seat and try to vote, even though he knew he probably wouldn't actually get registered and would probably go to jail," Butts says. "How do you convince someone to do that?

"I think it's evidence of being young and not knowing what your limitations are and what you can't do yet," he adds. "It's important for young people today to understand how much power there is in not knowing what you can't do."

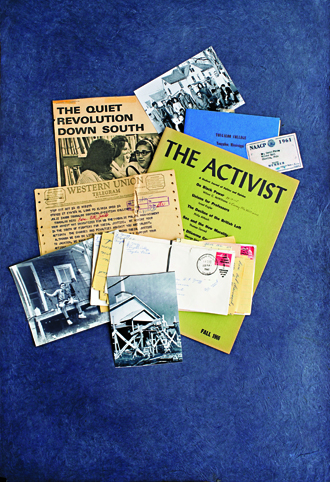

MEMENTOS OF A MOVEMENT: When Julie Zaugg '64 was arrested for trying to integrate a church in Jackson, Mississippi, while on a college exchange with Tougaloo Southern Christian College, Oberlin Student Council sent a telegram of support signed by 250 students (center); lower left, Matthew Rinaldi '69 on a porch in Kosciusko; top and bottom, Carpenters for Christmas. (Tanya Rosen-Jones '97)

MEMENTOS OF A MOVEMENT: When Julie Zaugg '64 was arrested for trying to integrate a church in Jackson, Mississippi, while on a college exchange with Tougaloo Southern Christian College, Oberlin Student Council sent a telegram of support signed by 250 students (center); lower left, Matthew Rinaldi '69 on a porch in Kosciusko; top and bottom, Carpenters for Christmas. (Tanya Rosen-Jones '97)Examining Equality: Here in Oberlin

By the fall of 1962, Oberlin students had turned their full attention to the movement in the South. At the same time, movement leaders were examining the subtler yet equally insidious racial inequities in the North. It did not take long for Oberlin students to follow suit.

Despite the prevailing rhetoric of brotherhood and equality and of Oberlin as a leader on issues of race, it was difficult to ignore the fact that there were few students of color on campus; only 15 African American students had graduated with the Class of 1960. Although more were admitted in later years thanks to a Ford Foundation grant, they were still a very small minority. Some of these students were more comfortable with this than others.

"I was always the marginal man, but when I got to Oberlin, I was very comfortable because I felt like we were all marginal people," Jacob Herring '65 says.

Other students of color felt more isolated and questioned Oberlin's reputation as a haven of diversity and progressive race relations. "I always felt somewhat separated, and I didn't feel that people were looking at me as a competent individual who came to Oberlin with a lot to offer," says Ruth Turner Perot '60. "It was kind of like you were tolerated, but you weren't necessarily accepted." Perot later became executive secretary of the Cleveland chapter of CORE and returned to campus in 1967 to give a speech on black power, which she called "an audacious prideful affirmation of self, without which Negroes cannot assume a respected position in an integrated American society."

"I felt there was an ivory tower quality to life at Oberlin where people were patting themselves on the back for being liberals, when I don't think they really understood what being a liberal meant," she says. "Being a liberal was a movement started by people who were disenfranchised and oppressed, so I was trying to testify for folks at Oberlin what it meant to be engaged in that struggle."

Gradually, Oberlin's NAACP chapter began to focus more on what was going on in its own backyard, collaborating with the town chapter to address unfair hiring practices and housing discrimination. "The black part of town often didn't have paved streets," explains Joel Sherzer '64, who was then president of the college's NAACP chapter. "Some of the houses didn't have toilets. It was like the South. And that was amazing for a college town that was considered to be a major player in the civil rights movement from the time of the Civil War. But … I don't think a lot of people were conscious of that because there was no forum to talk about it."

On November 16, 1962, the Oberlin Review ran a two-part insert titled "Race Relations in Oberlin." The article painted a stark portrait of a town divided, in which many businesses and institutions, from housing to the public education system to the local bowling alley, were split along strict color lines. "Oberlin, Ohio, is a town with a reputation for liberality," the article began. "This liberal reputation is a reflection of Oberlin College, long known as a leader in the struggle for Negro equality. This liberal reputation…is unjustified." The article served as a wake-up call to student activists who had come to Oberlin believing in its progressive history.

Ruth Turner '60 in Cleveland

Over the next few years, activists on other northern campuses would experience similar revelations. "As things moved north, there was more anxiety," says Marcia Aronoff '65, then leader of Oberlin Action for Civil Rights (OACR). "The southern discrimination and the laws of the South were easier for a lot of folks in the North to see as bad, as opposed to more subtle housing discrimination or employment discrimination in the North."

Over the next few years, student activists turned toward local civil rights issues, conducting surveys of local businesses' hiring practices and tutoring at "Freedom Schools" (created to shore up inequitable educational facilities and teach about black history and culture) during the 1964 boycott protesting de facto segregation in the Cleveland public schools. In 1963 the NAACP orchestrated a widely attended picket against Oberlin's Northern Ohio Telephone Company for discriminatory hiring practices, an action that the Oberlin Review referred to as "the first major display of civil rights interest since the Wellington Rescue."

During this period, students at Oberlin and colleges across the country continued to head south in significant numbers, but the days of believing that racism and discrimination were exclusively "southern" problems were gone. Now, activists were forced to confront the uncomfortable truth that the injustice they were fighting was as present in the North as it was in Montgomery, even if it wasn't as pervasive and brutally enforced by the physical terror of the Deep South's system of white supremacy.

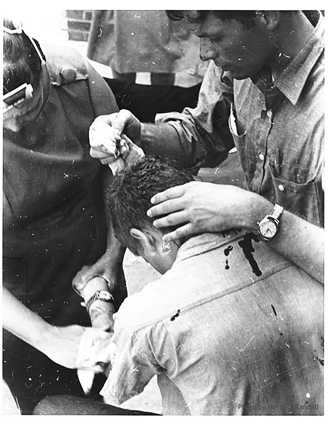

David Owen '64 and other volunteers were beaten with steel rods while canvassing in MIssissippi. (Oberlin College Archives)

David Owen '64 and other volunteers were beaten with steel rods while canvassing in MIssissippi. (Oberlin College Archives)Freedom Summer

In the early spring of 1964, a 150-word notice appeared in the Oberlin Review advertising an upcoming OACR meeting to recruit members for an SNCC-sponsored summer project in Mississippi focused on voter registration drives. Similar calls went out to students across the country, urging them to participate in what SNCC staffers were calling "Freedom Summer."

The goal of Freedom Summer, explains Oberlin Professor of History Renee Romano, was to draw national attention to efforts to mobilize black voters in the South by sending volunteers to Mississippi to do canvassing and staff Freedom Schools, which taught African Americans how to pass the racially biased voter registration tests. Oberlin was targeted in part because of its history, but also for its potential pool of upper middle-class volunteers.

"Freedom Summer organizers weren't as interested in northern black students," Romano explains. "They wanted students who could attract press attention and who could potentially change the dynamics of FBI involvement, and they reasoned that the FBI might pay more attention if white students went south. Organizers also wanted young people who could pay their own way, so it was mainly students from privileged economic backgrounds who could participate." For this reason, some of the more active members on campus, including Marcia Aronoff '65 and Jerry Von Korff '67, were unable to participate.

Students also faced the challenge of having to convince their parents to let them spend their summer in Mississippi—a state that NAACP president Roy Wilkins Jr. criticized for its unassailable record of "inhumanity, murder, brutality, and racial hatred." David Owen '64 said his father, a professor at CalTech, gave him permission to go, but only after a civil rights activist who was speaking at CalTech persuaded him. "The guy told my father that Freedom Summer was a well-organized project, and that he should be proud of me for being interested. So I went."

After an exhaustive screening process, the Freedom Summer volunteers headed to Oxford, Ohio, for a week-long orientation session. Training had barely begun when news arrived that three civil rights workers—staffer Mickey Schwerner; Meridian-native and longtime CORE volunteer James Chaney; and Andrew Goodman, a college student and Freedom Summer volunteer—had mysteriously disappeared while investigating a church burning in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The new volunteers had little time to decide whether or not to continue. "There was a vast amount of soul-searching among the volunteers and staff that was fairly public and very emotional," remembers Vicki Halper '66, a Freedom School volunteer in Greenville, Mississippi. "As the days passed and nothing was discovered about these three guys, the atmosphere got more and more tense."

While some volunteers did return home, often at the urging of their parents, most stuck with the training, knowing full well the risks involved. "It was no longer a question of whether or not civil rights workers would be in danger," recalls Michael Lipsky '61. "Everyone in that room had to decide whether they were willing to do what they had set out to do. The illusion of going into this without any prospect of danger was no longer available."

"I didn't once think about leaving Mississippi. That just wasn't going to happen. We still had a job to do."

After training in Oxford, volunteers were placed in cities throughout Mississippi. Some taught in Freedom Schools while others provided administrative support: Lipsky was placed in charge of monitoring the two-way radios that allowed people in the field to be in touch with the office. "If people in the field didn't call in at assigned times, a search for them could begin quickly," he says. "That gives a good sense of the tension under which people were working."

Some of the volunteers did voter canvassing, widely considered to be the toughest and most dangerous job. Canvassers often faced harassment from local whites and resistance from African Americans who feared retribution from the white community if they were seen in public with civil rights workers. "People were so scared, and rightfully so. You just felt it," remembers Martha Honey '67, who taught and did voter registration in Mileston. "Some people would latch the door when you came around.David Owen '64 Others would be quaking because there was a white at the door."

It was while canvassing in the white part of Hattiesburg that Owen and two other volunteers were beaten with steel rods by local white men. The attack was highly publicized in the local and national media; Owen was hit in the head multiple times and required stitches. Still, he was back at work canvassing in a different neighborhood a mere two weeks later. "After that happened, I remember being more careful and worried at times, but I wouldn't say I was fearful," he says. "I felt safe, and there were a bunch of people who would help protect me. I didn't once think about leaving Mississippi. That just wasn't going to happen. We still had a job to do."

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the "Freedom Vote"

Freedom Summer was created in large part to build up the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), an alternative party that aimed to challenge the all-white power structure of the state's regular Democratic Party. In the months leading up to the Democratic convention in Atlantic City, the MFDP hoped to fill the Mississippi seats with its own candidates, who would be elected by black and disenfranchised voters who were traditionally excluded from state elections.

When the Democratic National Convention refused to seat MFDP delegates at the convention, some of the Freedom Summer volunteers felt disillusioned with the work they were doing there. Others, like Owen, felt that the ends of the Freedom Summer project were not as important as the means by which they were achieved. "I was impressed by how far we had come since May, before Freedom Summer started and when the white southern establishment controlled the press, to the convention, where that line didn't hold," he says. "Even if we hadn't won, over three or four months a lot had changed in terms of public perception."

"I remember coming back and saying to a friend of mine at Oberlin that the fear was so thick you could cut it with a knife."

What Owen and the other Freedom Summer volunteers would eventually realize was that the project had represented a shift not only in public perception, but within the ranks of SNCC and other civil rights organizations. Many higher-ups were frustrated with the movement's unconditional reliance on nonviolence and with its high concentration of upper middle-class white youth.

At the same time, many student volunteers felt they were, as Honey puts it, "cannon fodder." "We were there to provoke violence and bring attention to [the situation in the South], because black Mississippians couldn't do it on their own," she says. "In a sense, we'd kind of done that, but there was also this rise of young black people saying, 'This is our movement, and we want to run it.'…By the end of the summer, we were told this was a period of transition and we had played our role and now it was time to leave."

Not all of Oberlin's Freedom Summer Margo Cairns '64volunteers left immediately afterwards: Owen moved from Hattiesburg to Laurel, Mississippi, while Linda Davis '66, who taught at a Freedom School in Ruleville, stayed on for an extra year to teach and build a recreational center. Most volunteers, however, returned to Oberlin after the summer ended to continue their studies, albeit not without difficulty. "It was really hard to resettle into student life after that," Honey admits. "My learning was really from all those wonderful activists…I don't think my parents got their money's worth for my coursework."

Nonetheless, most of the Freedom Summer volunteers felt profoundly changed by their experiences in the South, as did the student activists who watched Freedom Summer unfold. Although the debate about the role of middle-class whites in the civil rights movement continued, many students who were inspired by the Freedom Summer volunteers continued to travel to Mississippi over the course of the next year.

In the fall of 1964, OACR put out another call for volunteers in the weeks leading up to the election, or "Freedom Vote," organized by the MFDP. Seventy Oberlin students responded to the request, with 24 ultimately selected. As during Freedom Summer, volunteers again worked to mobilize the rural African American community in Mississippi, holding massive voters' rights rallies and passing out leaflets in front of courthouses (an activity that landed four Oberlin students in jail).

The dangers of canvassing in rural areas of Mississippi were still very much present. Margo Cairns '64 recalls spending the night in a safe house after a shooting: "We spent the night under the beds instead of on the beds, because we were worried they'd come by again," she remembers. "That was one of the more frightening experiences. I remember coming back and saying to a friend of mine at Oberlin that the fear was so thick you could cut it with a knife."

Carpenters for Christmas

Oberlin's Carpenters for Christmas before setting off on their trip to Ripley, Mississippi, to rebuild an African American church that had been destroyed in a fire. (Oberlin College Archives)

Oberlin's Carpenters for Christmas before setting off on their trip to Ripley, Mississippi, to rebuild an African American church that had been destroyed in a fire. (Oberlin College Archives)A few days after the Freedom Vote, a church that had been used as a Freedom School and voting station — the Antioch Missionary Baptist Church in Ripley, Mississippi — was burned to the ground. Although the fire was referred to as an accident by the Mississippi press, the church was one of many black churches that had been destroyed in the aftermath of the Freedom Election. "A lot of these churches were burned, and nothing was happening," recalls OACR Cochair Von Korff '67. "Nobody was standing up for them."

Von Korff, OACR cochair Aronoff, and then-Oberlin Professor of Philosophy Paul Schmidt and his wife, Gail Baker Schmidt '55, came up with the idea to travel to Ripley and rebuild the church. The group called themselves Carpenters for Christmas and cast themselves as missionaries to avoid being labeled northern "agitators."

"I was very enthusiastic because nothing would be more appropriate and less threatening than hearkening back to the image of Jesus as carpenter," Aronoff recalls.

The strategy paid off: Carpenters for Christmas received a front-page story in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, as well as national news coverage when the story was picked up by news wires. Checks flooded in from all over the country, and by the time the Carpenters left for Ripley on December 20, they had raised more than $10,000—well over the amount required to rebuild the church.

For nearly two weeks, the Carpenters worked on the foundation of the church, laboring from dawn till dusk in ankle-deep mud. The volunteers, which included Joe Gross '67, Stan Gunterman '67, Randy Furst '68, and Mary Miho '68, among many others, were warmly received by the African American community, who thanked them for their efforts by bringing them lunch every day. Local whites, however, were not so gracious: reports of gunshots and mailbox bombings near the construction site received national coverage, prompting a string of fiery editorials in the local papers responding to the negative publicity.

"We didn't have the roof up yet, so we had a morning Christmas service under the open sky. It was pretty cool."

"The people in Mississippi are very sensitive about these people's motives," the white minister of the Ripley Methodist Church said to one local newspaper. "We wish that they were sincere rather than seeking publicity." A county judge quoted in the same article was even more indignant, denying that any of the white locals would have set the fire in the first place. "We are the best of friends with our niggers down here," he insisted.

Still, despite the threats and intimidation tactics, the Carpenters kept working. "It was great to see what we could all do together, people who had no skills to offer," Aronoff says. "There was just a feeling of satisfaction at being able to actually construct something and to see it rise every day." At night, they took turns standing watch from a shack across the street. "We were 19 years old," Von Korff remembers. "You know, we were going to build that church and by golly, we were going to make sure that as long as we were there, it didn't get burned down again."

By Christmas morning, the frame of the church had been assembled. Under the lens of NBC news cameras, the Oberlin and Ripley volunteers attended Christmas morning services in the newly built church. David Reed '65"We didn't have the roof up yet, so we had a morning Christmas service under the open sky," remembers OACR member David Reed '65. "It was pretty cool." Carpentry tools hung on a wall behind the pulpit, which a minister suggested was a reminder that "Jesus was also a carpenter."

The experience was deeply moving for the volunteers, many of whom had worked at the church during the Freedom Election or attended voter registration rallies there. "I look back on my time down south as one of the greatest adventures of my life," says Alex Jack '67. "Carpenters for Christmas was one of the most creative and meaningful of these projects. Because it wasn't just protesting, it was doing something constructive. It was rebuilding."

For 10 days, the Carpenters and church members toiled in the mud for hours on end, rebuilding the church brick-by-brick. "The need to rebuild comes out of evil," said David Jewell, Oberlin associate professor of Christian education, in his Christmas sermon. "But the desire to rebuild comes out of love." Blacks and whites had worked together, side-by-side, during the construction, and during the Christmas service they worshipped together under one roof as well.

Although the Carpenters had built a church for the black community, the integrated Christmas morning service was one of the first glimpses of what a future Mississippi could look like: blacks and whites living and working and worshipping together without fear. The skeleton frame of a new Mississippi had been built, and Oberlin students could now point to the church and say that they had a hand in its building.

Looking Northward Once Again

During the following years, OACR's attention turned back up north, where the organization staged protests against building trade discrimination and segregated housing practices in Cleveland. OACR sent nearly 100 Oberlin students to Erie, Pennsylvania, to picket the headquarters of the Hammermill Paper Company for its plan to build a plant in the segregated city of Selma, Alabama. Many students were arrested for blocking the train tracks used to transport materials into the plant. Although the FBI and the mayor of Erie pressured Oberlin's administration to release the students' names, then-President Robert Carr refused to comply. In an August 1965 speech, he proudly noted that "no disciplinary action has ever been taken by the college against students or faculty members for such participation" in civil rights activities.

"We, collectively, as a movement, really changed the Deep South. Nothing can change that victory. Mississippi really is a different world now."

By now, students were starting to realize that their actions were affecting real change, both locally and nationally. OACR and an SCLC leader negotiated an agreement with Hammermill: the company agreed to hire African American workers and support voter registration efforts. In the world outside Oberlin, President Lyndon Johnson signed the landmark Civil Rights Bill of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, prohibiting racial segregation in public facilities and discriminatory voting practices against African Americans.

Although few students believed such gains could undo the effects of decades of oppression and inequality, the legal triumphs of the civil rights movement nonetheless weakened its strength on campuses. The antiwar movement, as well as protests against campus social rules—like those governing dorm room visitations between men and women—were steadily gaining ground, and activists' focus shifted toward those efforts.

"We naively thought that because there had been legislation on civil Matthew Rinaldi '69rights, voting rights, etc., that the battle was…not won, but there had been sizable progress," Honey says. "And Vietnam was looming. Because there was a draft, and every male we knew was facing it, it was more personal."

Another factor in the changing face of the movement on campus was the increased enrollment of African Americans later in the decade (steadily climbing from 1.6 percent of the total in 1963 to 6.7 percent in 1969), and the concurrent surge of black power, which advocated for African Americans gaining political and cultural agency by, in part, taking more control over the direction of the movement. "The concept of black power emerged because it was clear that if you were going to tackle social and economic issues, you would have to have a position of power and import to change the system itself," Ruth Perot says. "Black power became a call for action because we realized that we were not going to tear down those big barriers from systemic inequality in the ways we functioned before."

The Tougaloo Story

In the mid 1950s, Oberlin College started a cultural exchange program with two historically black Southern universities: Fisk University in Nashville, and Hampton University in Virginia College. In the early 1960s, another historically black college joined the list: Tougaloo Southern Christian College, a private, four-year liberal arts college in Jackson, Mississippi.

Founded as a predominantly African American teachers’ college, Tougaloo was known for being one of the few integrated higher education institutions in the South. Its reputation as a hotbed of civil rights activity was well-established, prompting then-lieutenant governor Carroll Gartin to refer to it as a haven for “queers, quacks, quirks, political agitators, and possibly some Communists.”

In the fall of 1962, the college launched a weeklong exchange program with Tougaloo. The goal of the program, a Review op-ed stated, was to “open up forums of discussion on the Southern experience.” That experience was jarring for many of the students on the program, most of whom had never traveled to the South or witnessed the effects of segregation firsthand.

“Going to Tougaloo really opened my eyes to what was going on in the South at the time,” says Muriel Hamilton ’65, a participant on the exchange program. “We met students who were very active in the movement, and it was incredible to hear from people on the front lines about what was going on in Mississippi.” Marcia Aronoff ’65 also attended the exchange. “Seeing white supremacy signs, hearing [segregationist governor] Ross Barnett speak — it all seemed so wrong in the U.S.A.,” she recalls. Both Aronoff and Hamilton would devote the rest of their Oberlin careers to the civil rights movement, organizing various trips South with Oberlin Action for Civil Rights (OACR).

In Jackson, Hamilton and Aronoff and two other Oberlin exchange students were confronted by a sheriff deputy for attempting to enter a whites-only waiting room at the bus station. They later had to return to Jackson to testify against the sheriff after a racial discrimination lawsuit had been filed against him. “That was my first experience of someone blatantly telling me: No, you can’t do this because you’re black,” Hamilton says.

Both Aronoff and Hamilton were profoundly affected by their experience at Tougaloo, organizing various trips down South and devoting the rest of their careers to civil rights. Encouraged by the positive feedback to the weeklong program, the Oberlin administration decided to extend the Tougaloo exchange program to a full semester the following year.

In 1963, then-junior Julie Zaugg ’64 volunteered to be the first student on the semester-long exchange program. Upon her arrival in Jackson, she quickly became immersed in the thriving activist scene, participating in her first organized civil rights action by attempting to integrate a Methodist church with two other Tougaloo students. Although the church visits had been going on without incident for the past few months, the three were arrested by Jackson police on October 6, 1963.

“It was a surprise, and nobody was expecting it,” Zaugg recalls. “We figured we’d just turn around and head home if we were denied access. But when we got there we discovered that the police had followed us from campus — they’d had a car trailing us to the church the whole time. I think they were just fed up with the church visits, and they thought this would put an end to it.”

The girls were taken to a county jail, where they were charged with trespassing on church property and disturbing public worship. Bail was set at $1000. Later, they were charged with an additional six months jail time before the national Methodist church raised their $3000 total bail. Free to go, Zaugg and the two students returned to the Tougaloo campus to tell their story.

Two weeks later, Zaugg was arrested again in front of another Methodist church, this time with eleven other protesters. She spent almost a week in jail before the group’s attorney, famed civil rights lawyer William Kunstler, got the case removed to federal court.

The case attracted national press attention. Zaugg and her family received letters from well-wishers all across the country, including a supportive telegram from Oberlin signed by hundreds of students. “It went on page after page after page,” she recalls. “It was a wonderful gift.” Her family also received hate mail from white supremacists, including bomb threats and obscene late-night telephone calls.

“It was terrifying to learn that there were people out there who thought like this,” she says of the hate mail.

When Zaugg returned to Oberlin for her final semester in the spring of 1964, she found that she had little interest in participating in the movement on-campus; although she attended a string of local demonstrations, she found her dramatic experience in Jackson had left her feeling fragile. “I could never sing freedom songs because I would burst out crying,” she says. “So I just kind of withdrew…when you have an experience like that, it just gets into you somehow. One just never is the same after that.”

Over the next few years, dozens of Oberlin students followed in Zaugg’s footsteps, flocking to Tougaloo to get a firsthand glimpse of Southern life that transcended what they saw in front-page articles and news footage. Although not all of them came to Tougaloo intending to engage in full-blown activist efforts, some, like Zaugg and Hamilton, found themselves politically radicalized by their experience.

Others, like Marjorie Waite ’65, viewed their time in Mississippi more subjectively, reflecting on the semester as an opportunity for cultural education and personal growth. “I went down to Tougaloo not with the view of making a big difference on campus or using it as a base station for civil rights activism, as much as it was a personal effort to immerse myself in the culture down there,” Waite remembers. “It was like getting to know a whole other universe, but it was a terrific experience, and I made some lifelong friends in the process.”

Like a number of civil rights groups across the country, OACR was largely a white, middle-class organization. The dialogue taking place on a national level regarding the role of whites in the movement was happening on campus as well. "There was a lot of reflection [within OACR] about how to remain engaged and at the same time be respectful to both black sensitivities and desires to ensure that they were leading in their fight," Aronoff says. These conversations stirred mixed emotions in OACR members, both black and white: some encouraged the ascendancy of black power, while others were uncomfortable with what they perceived to be the movement's exclusionary aspects.

Still, students continued to journey south, attempting to integrate public institutions and lead voter registration efforts in Alabama and Mississippi. A number of students and alumni attended the famed march from Selma to Montgomery in March 1965, as well as solidarity marches in Washington, D.C., and Cleveland. Glanetta Miller '69 and Penny Zolbrod '69 worked with Charles Evers in Natchez, Mississippi. Students also returned to Mississippi to help aid displaced sharecroppers and assist the MFDP with voter registration efforts during spring break in 1966.

By 1966, newcomers to OACR now had the benefit of insight from activists who had made previous trips down south. "I remember driving into Mississippi and listening to blues on the radio, and someone who'd been there before me shifting into a different state of being, in terms of hyper-alertness of our surroundings and being on guard, telling us to be mindful of cars following us and police and anything unusual that could be a threat," Matthew Rinaldi '69 remembers. "And that was probably the first training I ever got."

Rinaldi was part of an Oberlin contingent that included Honey, Bill Sherzer '66, James Hudock '67, Don Salisbury '68, Richard Klausner '68, Bonnie Beshears '69, Ann Shaftel '69, and Dan Cleverdon '70. Many seasoned volunteers and newcomers were shocked when MFDP organizers in Kosciusko, Mississippi, supplied volunteers with guns, though many Mississippi civil rights workers and their hosts had been arming themselves for years and taken the position that they would defend themselves against violent attack. The Oberlin volunteers quickly discovered why when members of the Ku Klux Klan shot at their Freedom House in the middle of the night. Salisbury had been hit with buckshot in the chest and went to the local hospital, and a slug grazed Klausner's head. Rinaldi and Hudock fired back, and the attackers fled, pursued by an MFDP organizer and Cleverdon. The incident made national network news. An FBI file on the case shows the attackers were linked to Sam Bower's White Knights of Mississippi, the same group that murdered Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner.

It was a sobering experience for some of the activists, particularly those who had been reared on the principles of nonviolent protest. "After they shot at us, somebody put a gun in my hand because [the injured students] had to go to the hospital," Sherzer remembers. "I sat there with a pistol in my hand all night. And when that was over, I swore I would never return to the South because I never wanted to hold a gun again."

Though shaken by the event, Salisbury says the volunteers were not deterred. "I have never since experienced such fear," he says. "Never‑ theless I can proudly state that we decided as a group not to back down and we continued our registration work in Kosciusko."

The 1966 trip to Mississippi was the last official, OACR-sponsored trip to the South. Although a few students traveled on their own, there was a growing sense of disillusionment among some of the OACR activists with their work in the South and their role in the movement as a whole. As OACR copresident Bernie Mayer '68 noted in a 1966 Review editorial: "In the future, college civil rights groups, especially Oberlin's, are going to have to work more steadily in the North and not look so wistfully to the occasional glamorous trip down south."

The organization focused on strengthening its bond with the Cleveland chapter of CORE to combat housing discrimination and focus on urban renewal; members also focused on volunteering for the campaign of Carl Stokes who, in 1967, became the first black mayor of a major American city when he was elected mayor of Cleveland. Charlie Butts, who had recently graduated, was his campaign manager. "It was on the [Nov. 17, 1967] cover of Time magazine: 'Negro election victories, Cleveland's Mayor Stokes,'" Allen Weintraub '67 remembers. "We thought we were going to change the political map."

Shifts in Focus

This shift in the focus of the movement from south to north was accompanied by a burgeoning black power movement nationally and on campus. In the fall of 1967, the Oberlin College Alliance for Black Culture (OCABC) was founded. The group sought to create an inclusive, safe space for students of color to discuss their own experiences; pushed for the introduction of black history, literature, arts, and culture courses into the curriculum; and advocated for an all-black program house (soon to be known as Afrikan Heritage House, which opened in 1969).

OACR effectively placed itself in the new group's control, agreeing not to interfere with its agenda and to support its programming when requested. The split made some veteran civil rights activists feel excluded from a movement they helped to build. Others felt the new push was necessary, since OACR had been led through most of its history by white activists.

"It was an important demarcation point," Mayer says. "That was when we began to grapple with what it meant for black consciousness to develop, and how important that was for change to occur."

At the same time, more student activists were turning toward the antiwar movement, and OACR officially disbanded later that year. Yet the desire to seek racial equality and social justice carried over through the rest of student activists' lives. Some devoted their entire lives to the movement; others became lawyers, judges, teachers, and members of the clergy. Many credit Oberlin with giving them a voice as activists; others reflect on their time on campus as a conduit for the expression of social justice principles that had already been deeply embedded within them. "We, collectively, as a movement, really changed the Deep South," Matthew Rinaldi says. "Nothing can change that victory. Mississippi really is a different world now."

Their role in that victory began for some Oberlin students and alumni with a moment of soul searching.

"We saw the young people in Greensboro sitting down at the lunch counter," Ruth Perot says. "We saw the Freedom Riders go down and get beaten. We saw other people making those kinds of commitments, putting their lives on the line and risking brutal beatings and jail and death, and if they could do that, then surely we could do something ourselves to bring about change in our own environments. So the question was simple: am I going to stand on the sidelines and watch this, or am I going to be a part of something bigger than myself?"

In preparation for this story, the alumni magazine, with the help of Marcia Aronoff '65, Martha Honey '67, and Matthew Rinaldi '69, asked alumni involved in the civil rights movement to tell us about their experiences. The response was staggering. We received more than 100 recollections via phone, mail, hand-written letters, e-mail, and Facebook from dozens of alumni who played a role in the ongoing struggle for racial equality. Writer EJ Dickson drew from many of these stories for this article, but there simply isn't room to print them all. During the upcoming months, the alumni magazine will post these stories — e-mail, transcripts, recordings — online as we work with Oberlin College Archivist Ken Grossi to build a digital collection.

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.