Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2007 Vol. 102 No. 3

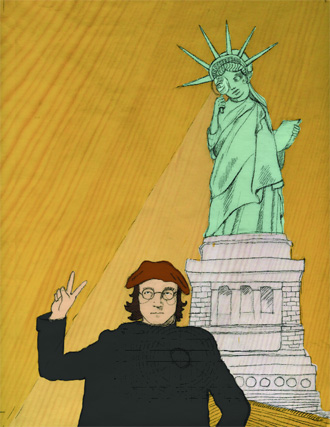

Tryin’ to Get Some Peace!

Illustration by Annie Olechowski

Illustration by Annie Olechowski John Scheinfeld

John Scheinfeld

Filmmaker John Scheinfeld’s latest project explores John Lennon’s immigration fight.

The political awakening of John Scheinfeld ’75 came somewhere between his dorm room and his plate of Crunchy Cod.

“You practically had to sign a petition just to get into Dascomb dining hall,” he recalls with a chuckle. “You’d be walking up saying to yourself, ‘Oh, what cause is it today? Save the toothpicks?’”

As a sociology major (“basically because I loved Professor James Walsh”), Scheinfeld was undoubtedly engaged in the turbulent political landscape of the early 1970s. But he also spent his college years feeding his love of films at the Apollo Theater on East College Street. “We called it the ‘Appalling’ because it was pretty run-down,” he says, “but I still remember seeing The Godfather there and being completely riveted.”

Thus was forged a career path that combines Scheinfeld’s avid interests in popular media and sociopolitical issues. The highest-profile product of that 30-year blend is The U.S. vs. John Lennon, a feature documentary released in theaters last fall by Lionsgate Films, the company behind Oscar-winner Crash and Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11. Scheinfeld cowrote, coproduced, and codirected the film with David Leaf. It took in $1.1 million at the box office—more than respectable by documentary standards—and arrives on DVD in February.

In 1993, after a long stretch working in prime-time television, Scheinfeld partnered with Leaf to create documentaries about musical figures like Harry Nilsson, Brian Wilson, and Nat King Cole. The U.S. vs. John Lennon is in that vein, but more ambitious. It features 40 original Lennon songs on its soundtrack, plus eye-opening archival footage from the late 1960s and early ’70s detailing Lennon’s immigration fight with the Nixon administration. Through interviews with the likes of Yoko Ono, Mario Cuomo, George McGovern, Angela Davis, and Gore Vidal, it lays out a convincing case that the singer was seen as a subversive threat whose deportation back to England might well have saved the beleaguered White House a few headaches. The DVD version includes 50 minutes of additional footage.

One especially memorable sequence covers the unusual honeymoon staged by Lennon and Ono in 1969 at various hotels around the world. Knowing their wedding would attract global media attention, they invited cameras and reporters into their room, where they staged an anti-war “bed-in.” Lennon’s song The Ballad of John and Yoko commemorated the event: “Drove from Paris to the Amsterdam Hilton / Talking in our bed for a week / The news people said / ‘Hey, what you doin’ in bed?’/ I said, ‘We’re only tryin’ to get us some peace!’”

Beatles fans and Baby Boomers are a natural audience for the film, but Scheinfeld believes the parallels with today’s political climate appeal to a younger crowd as well. “You had an administration so wary of its citizens that it started spying on them and an unpopular war turning public sentiment against the White House. Sound familiar?” Many critics keyed on that point in reviewing the film last fall. “The production is not only poignant, but topical,” affirmed the Village Voice’s J. Hoberman. Michael Sragow in the Baltimore Sun agreed: “It offers proof that Lennon’s wit and art are everlasting.”

Ono, who cooperated extensively with the filmmakers, said the songs on the soundtrack, which includes two previously unreleased tracks, “have become relevant all over again. It’s almost as if John wrote these songs for what we are going through now.” It’s worth noting that another Obie, stage and film director Julie Taymor ’73, has also been tracing the Lennon link between then and now. Her Beatles-driven movie musical Across the Universe is scheduled for release this year.

Scheinfeld says the resonance of the Lennon story was amplified by his Oberlin experience—not just at the dining hall, but at a time when the protests of the 1960s over Vietnam and civil rights had segued into a thorny decade marked by anxiety. Signs of the times included a global oil crisis, a Life magazine cover story about Oberlin’s co-ed dorms (“revolution on campus”), and a College-run “crash pad” in Wilder Hall that helped students recover from bad drug trips. Presiding over the College was the divisive Robert Fuller ’55, who, at 33, was the youngest president in Oberlin history and also its most controversial. “I really liked a lot of Fuller’s ideas, but you were either with him or you were against him,” Scheinfeld says.

The Fuller-era dialogue on campus has proven a steady source of inspiration for Scheinfeld ever since. “We used to have something called ‘Friday Night Crisis,’ where everybody in the dorm would get together and ‘rap’ about all of the things going on around the world,” Scheinfeld says. “In conversations like that, I learned about my own views and that experience wound up being a real foundation.”

Dade Hayes is the assistant managing editor of Variety in New York.