Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2008-09 Vol. 104 No. 2

Around Tappan Square

(photo’s by Dale Preston ’83)

(photo’s by Dale Preston ’83)

Obama Wins, Oberlin Reacts:

A Student’s Perspective

Almost a month had passed since I’d boarded one of the buses the College had provided to transport early-voting students to the Lorain County Board of Elections. Once there, I’d waited in line for six hours, thinking about the reports I’d heard about unreliable voting machines. In the end, I opted to wait the extra 10 minutes for a paper ballot. Besides, this was my first election, and I wanted my vote marked on paper. I wanted to hold it in my hand.

The week before November 4, the campus had developed a sound track of “Obama,” “voting,” and “canvassing,” and I, like everyone else, was invited to distribute pamphlets door-to-door and to trace my finger down long lists of registered Democrats to call with a reminder to “get out and vote!”

On election day, students busted into co-ops and dining halls, sounding one last call for the political procrastinators among us. By that time I was pretending to do homework in my friend’s cramped dorm room; one eye was on my Arabic book, the other on my e-mail and cell phone. I must have gotten a dozen messages from family and friends that night offering information on how the election was shaping up in their states; North Carolina, California, and Maryland were all turning blue. But when CNN finally flashed, “Obama predicted 2008 president-elect” over its red and blue map, the bubble of tension burst. Students poured out of dorms to shouts and cheers, ecstatic hugs, and magnificent kisses. In my hurry to get to North Quad, I ran out onto the grass in my socks.

As the candidates’ concession and acceptance speeches ended, a parade of students from south campus marched up to join us, and in a moment of coherence, we spread out into a huge, hand-held circle around North Quad. The girl next to me took my hand; she was crying. Roars of elation rose and fell around the circle before it finally broke, people racing in twos and threes toward the center with hands held or arms raised. Exhilarating chants of “USA” and “Yes We Can” loosed into the night. As if in answer to our newborn patriotism, a Fourth-of-July-like spray of fireworks shot into the sky. For once, the ever-present campus fireworks were relevant. Their cracks and booms were shouting with us.

We were united that night—students, professors, security officers—collectively releasing a tense breath we realized we’d been holding for eight years. We radiated a mix of relief, elation, and an unfamiliar faith we had suddenly regained in each other. At that moment, Justin Emeka, associate professor of African American studies and theater, jumped out of his car, which was stopped at a red light on the corner of North Professor and West Lorain streets, and hugged passing students. Minutes later, he gave an impassioned, impromptu speech from the top step of the gazebo in Tappan Square. The jazz band, which had been playing When the Saints Come Marchin’ In, momentarily hushed, and to the crowd of students from all over campus Emeka shouted, “This is your time! This is your time! This is our time.”

That night, we held our victory—in our votes and in the hands we clasped tightly, in joy, in recognition, in hope.

Miles away, my parents, excited about the election, had fallen asleep before the results came in. But by 7:38 the next morning, I had an e-mail message from my father. In the subject line he wrote “victory,” and the message was just one word, “Alleluia!”

Election Roundup

A panel of politicians and journalists spoke on campus November 8 to analyze the 2008 election and lead discussions on the top issues facing the Obama administration. Panelists included NPR reporter Kathleen Schalch ’78, tax policy expert Leonard Burman, and others. A few days later, the chairmen of Ohio’s Democratic and Republican parties led the panel “What Do the 2008 Election Results Mean for Ohio?” In December, Oberlin sponsored the symposium “World Views: Considering the United States’ Image Abroad in the Post-Bush Era.” Read more at www.oberlin.edu and in the spring issue of OAM.

(photo by Rachel Cotterman ’10)

(photo by Rachel Cotterman ’10) Oberlin Senior Named Rhodes Scholar

Lucas Brown ’09, an economics major and well-known advocate for sustainability issues on campus, was honored with perhaps the most prestigious postgraduate academic scholarship in the world: a Rhodes Scholarship. He will enter England’s University of Oxford next October to pursue a master’s degree in economics.

Brown is among just 32 American students selected for the all-expenses paid scholarship, and he is Oberlin’s 15th Rhodes Scholar. “I’m surprised and humbled,” he says. “This has been such an incredible group effort—not only by the professors and friends who edited my essay or grilled me with practice questions, but by all of the students and staff involved in every project that ended up on my resume.”

Also the winner of a 2008 Udall Scholarship for environmental leadership, Brown helped found and design Oberlin’s Student Experiment in Eco-logical Design house, the only U.S. house to monitor its real-time total carbon footprint. He also cofounded the Oberlin Ecological Design and General Efficiency fund, which loans money for student-designed campus energy conservation projects and returns the energy savings to the fund as interest. He is a member of the campus environmental group that organized a car-sharing program and successfully lobbied the College to commit to a LEED silver standard in new building construction.

At Oxford, he says, he plans to study how environmental and business interests can work together, and then eventually work in his home state of Virginia.

In Other Words

“We need, simply, to wean the American food system from its 20th-century diet on fossil fuels, and put it back on a diet of contemporary sunlight. We need to stop eating oil and eat more sunlight.”

-Author Michael Pollan during his convocation talk, “In Defense of Food: The Omnivore’s Solution.”

“Racism will never end as long as the color of one’s skin is the basis of their identity.”

-bell hooks, renowned feminist and activist and former Oberlin faculty member, during her talk, “A Culture of Place: Search for Sustainability.”

“It’s difficult for a satirist these days. The world is a disaster.”

-Writer and satirist Gary Shteyngart ’95, author of The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, during an interview with the Oberlin Review following his campus talk.

“The story is always the most important thing. The history supports it. I don’t want [my books] to be a history lesson. The history just seeps into all the gaps.””

-Best-selling author Tracy Chevalier ’84 during a campus talk on her passion for writing historical novels.

“The mystery of Guantanamo Bay is: how can it be that after seven years of prisoners arriving there, that not a single detainee has been released by an order of the court, against the interests of the Bush administration. … The administration has released hundreds of detainees at its own discretion but has never been ordered by the court to release anyone they did not want to.”

-Linda Greenhouse, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and former New York Times Supreme Court Correspondent during her talk, “The Mystery of Guantanamo Bay.”

“When I was growing up in Knockemstiff, Ohio, it had a reputation for being a really tough place – a lot of fights, that sort of things. So then when I started writing, I took that reputation and I just kept cranking it up until I got as far as I could go with it without turning everything into some kind of cartoon.”

-Author Donald Pollock during an interview with the Oberlin Review, after he gave a talk at Oberlin.

Donors Give Back by Paying Forward

An anonymous $600 student loan given to John Picken ’56—and the donor’s refusal of repayment made with the suggestion that the young man instead return the favor to another student if he ever got the chance to in life—is the impetus behind Oberlin’s new Pay It Forward Alumni Scholarship.

More than 50 years later, John and his wife, Mary Sawyer Picken ’56, pledged a four-year, $5,000-a-year scholarship to a College or Conservatory student in need, with the hope that more alumni will be inspired to “pay it forward” as well.

Each new $20,000 pledge donated through the Pay It Forward initiative will support one student for four years. Scholar-ship recipients will be encouraged to correspond with their donors, and each student will be asked to “pay it forward” to a future Oberlin student when they have the financial means. Although “repayment” is not a stipulation for receiving the scholarship, John and Mary feel it is the moral obligation of students to take the clause seriously. “In a sense, it’s the gift that keeps on giving,” John says.

Besides, Mary adds, “taking some of the financial burden away from a student will help them enjoy the same kind of opportunities that students who don’t have to work can enjoy.”

Ben Jones ’96, vice president for communications at Oberlin, is one of the first Pay It Forward Alumni Scholarship donors. The concept, he says, appealed to him because it helped recognize the many people who helped him during his undergraduate studies. He also hopes that the scholarship will encourage a culture of giving among younger alumni. “Our Oberlin education and idealism mean nothing without the money to sustain them,” he says.

For more information, call the Oberlin Alumni Fund at (440) 775-8550 or e-mail alumni.fund@oberlin.edu.

(Courtesy of John Petersen)

(Courtesy of John Petersen) One Wet View

Professors and students performing research at nearby George Jones Farm got a bird’s-eye view of wetland vegetation last summer with the help of ariel photography.

Wetlands provide a broad range of ecological functions or ecosystem services. In agricultural landscapes such as Ohio’s, their role in processing and removing nutrients is particularly important.

Oberlin’s experimental wetland restoration facility consists of six wetland “cells” at Jones Farm, each about a quarter of an acre. In 2003, two of the cells were heavily planted. Two more cells received intensive planting and replanting over time, while two others were not planted at all, and instead allowed to “self organize.” Measuring the results are John Petersen, associate professor of environmental studies and biology; David Benzing, emeritus professor of biology; and their students, who perform ground-based assessments of biodiversity by carefully identifying the composition and abundance of plant species within each cell. Using aerial photography, the team can quantify and assess the changing spatial patterns of vegetation that develop in these maturing ecosystems.

“We are becoming increasingly aware that spatial patterning of vegetation has an important impact on ecosystem function,” Petersen says. “Our goal is to determine planting methods that result in a high degree of biodiversity and desirable ecological function.”

Jacob Grossman ’08, who worked as a research assistant in the experimental wetland systems, says the research “promises not only to help us understand how best to restore marshes, but it also helps us test our basic understanding of how natural marshes work.”

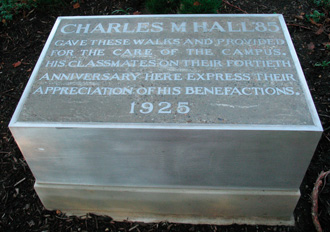

(Courtesy of Norman Craig)

(Courtesy of Norman Craig) Honoring Charles Martin Hall

Oberlinians gathered at the southwest

corner of Tappan Square in October to dedicate the restored plaque commemorating

Charles Martin Hall’s gifts to establish and maintain Tappan Square.

Emeritus Professor of Chemistry Norm Craig, who spearheaded the effort

to restore the plaque, spoke at the proceedings, entertaining the audience

with a brief history of Hall’s involvement with the square and of

the plaque.

Hall, a member of the Class of 1885,

made a fortune after discovering an inexpensive method for isolating

pure aluminum from its ore. An early adherent of the conservation movement,

he became a generous benefactor of Oberlin College. One of the projects

he funded was the renovation of Tappan Square, then called the Campus.

Once the site of several College buildings,

the 13-acre square was, during this period of the early 1900s, home

to three remaining buildings and the brand new Memorial Arch. The square

also was the focus of a heated debate. One faction advocated erecting

more buildings on the site. Another favored clearing all buildings and

transforming the space into a park for both town and gown to enjoy.

Hall sided with the latter, which eventually won.

When Hall died in December 1914, he bequeathed

what Norm called a “handsome sum” for an endowment for the maintenance

of the Campus. Hall also stipulated that the remaining buildings on

this site be removed by 1928.

With the help of Ken Grossi, acting College

archivist, Norm tried to chronicle the history of the plaque. However,

little information exists, leading Norm to conclude that the funding,

design, and installation of the plaque was the work of a few of Hall’s

classmates rather than a concerted effort by the entire Class of 1885.

From spring 1925 to September 2007, the

plaque lay embedded in the brick walkways at the center of Tappan Square.

“Although the plaque had survived well underfoot in a well-traveled

area for about 75 years, it had been damaged by snow removal done with

increasingly heavy equipment,” Norm wrote in a September 2008 report

to President Marvin Krislov. “In a casual repair, some of the letters

had been drilled and pinned into the base, and some cement had been

applied to cover dings. The aluminum frame had been damaged, removed,

and discarded. The loss of the aluminum frame made the plaque more vulnerable

to further damage. Some words and individual letters were completely

covered with the added cement.”

A year earlier, in anticipation of the

175th anniversary celebration of the community and College, President

Krislov had approved the plaque’s restoration. Emeritus Professor

of Art Paul Arnold contributed to the planning for this project, as

he has for other public monuments in Oberlin, and Ron Watts, vice president

for finance, and Tom Piccorelli, assistant vice president for facilities,

were also directly involved in the restoration process. With support

from the College, Nicholas Fairplay and Elizabeth Meadows of Fairplay

Stonecarvers restored the plaque. Because the plaque would likely be

damaged again if it were reinstalled at its original location, the restoration

team sought an aboveground and easily visible location; Lynda Khoury

of the city’s Historic Preservation Committee suggested the southwest

corner of the square.

Charles Martin Hall’s “close association with the Campus, or Tappan Square, as we call it, is well founded and should be remembered forever,” Norm told the group at the dedication ceremony. Now it will be.

Practice Makes Perfect

On this morning, like many mornings at Eastwood Elementary School in Oberlin, Annamica Ramdeen ’08 leads a class of second-grade students down the hall to the library before promptly heading back to her classroom, where she joins fellow student teacher Jamie Bollinger and mentor teachers Sharon Blecher and Gail Burton. They have just 30 minutes before the class returns, so they waste little time in reviewing student assignments. In pointing out one child’s classroom work, Ramdeen theorizes that the young student knows the material, but needs to dig a little deeper. Blecher, inclined to agree, first asks Ramdeen how she might help the child through the process. Mentors and students exchange comments, and then they move on.

Roneisha Kinney with Eastwood students (photos by John Seyfried)

Roneisha Kinney with Eastwood students (photos by John Seyfried)

Gail Burton, Annamica Ramdeen, Sharon Blecher, and Jamie Bollinger

Gail Burton, Annamica Ramdeen, Sharon Blecher, and Jamie Bollinger Burton’s busy schedule as a teacher almost stopped her from taking part in Oberlin’s Graduate Teacher Education Pro-gram (GTEP). Yet, that same busy schedule turned out to be positive, she says, because it serves as an example of what GTEP students can expect when they become full-time teachers.

Another positive, offers Blecher, is that mentoring becomes a two-way learning street. “The GTEP students make us think through our own teaching methods. It lets us get a new perspective.”

Across the hall, Roneisha Kinney ’08 leads her first-grade students in a counting exercise. Her mentor teacher, Alison Bigenho, displays approval with a quick thumbs-up. “Being in a classroom is vital to any teacher education program,” Bigenho says, “Why? Because anything can look good on paper or in a textbook, but how does it really play out in a classroom? Those are the realities of teaching and working with young children.”

Getting involved in GTEP was a no-brainer for Bigenho, because she had worked previously with Kathy Jaffee, the program’s site coordinator, and knew that whatever she was involved in would be top notch. Then there was the affiliation with a college as prestigious as Oberlin. “I knew—and know—that this program is going to be groundbreaking.”

Launched in 2008, Oberlin’s GTEP program combines one year of graduate study with a school-based internship, leading to a master’s degree in education and teaching licensure in early childhood (grades preK-3) or middle childhood (grades 4-9). Of the 10 students enrolled in the program, eight are Oberlin College graduates. All participate in the “immersion” aspect of the program, which offers above-average hours of real-life classroom experience.

“Theory is constantly informing and challenging the students’ practice in the classroom, and at the same time, that practice is informing and challenging the theory,” says GTEP Director Deborah Roose. “Unlike most teacher education programs, we weave the field experience directly into all the graduate courses. It may make for a more intense year, but we believe that less rigorous programs are simply doing a disservice to their students.”

Rigorous indeed. Even though Ramdeen, Bollinger, Kinney, and the other GTEP students already spend three days a week in the Oberlin Public Schools and take five graduate courses, they are also encouraged to attend staff meetings, parent-teacher conferences, and professional workshops. Second semester, they will add another day in the schools and, later in the spring, lead their own classrooms for four weeks of solo teaching.

In addition to their coursework and student teaching, GTEP students also spend time with their “community connection” family. Each student is matched with a non-college-related local family with whom they attend school and family functions through-out the year. This arrangement allows the GTEP student to act as an “education coach” to a child in the family, helping with homework and other activities. This out-of-class relationship is an important part of connecting with and understanding students, says Kinney. “Essentially in this role, I am involved in more aspects of the child’s life than academics.”

Even with all the time and labor that the program demands, GTEP students say they know that the immersion is well worth it. “I don’t have to file the ideas [learned in class] away until I’m officially doing my student teaching,” says Kait Beers ’03. “I can discuss them with my mentor and see how they work immediately in a classroom setting.”

GTEP is accepting applications for the academic year that begins June 15, 2009. For information, e-mail christa.champion@ oberlin.edu, call 440-775-8008, or visit www.oberlin.edu/teachereducation/admissions.

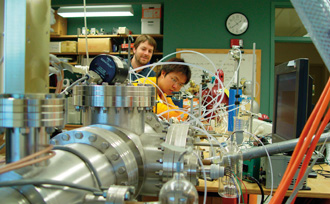

Elrod’s one-of-a-kind air instrument

Elrod’s one-of-a-kind air instrument What’s in the Air?

The Environmental Protection Agency can regulate ground-level pollutants like vehicle exhaust, but Associate Professor of Chemistry Matthew Elrod and his students want to know what happens to those compounds when they become airborne and form unhealthy ozone and particle pollution—better known as smog.

To help the EPA regulate air-polluting compounds, “we need to understand, from among literally thousands of different chemicals released into the air, which ones ultimately lead to the most harmful health effects,” Elrod says. “This is made even more difficult by the fact that many of these chemicals are converted to other chemicals by processes occurring in the atmosphere. In fact, the two most important air pollutants in the United States— ground-level ozone and particle pollution —are formed in the atmosphere. If we want to decrease their amounts, we need to learn a lot more about these chemical processes.”

Emily Minerath ’09 used Oberlin’s nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer to study how quickly chemical reactions can occur in airborne particles. She discovered a class of chemical reactions that might help explain the increase in particle pollution observed when natural chemicals emitted by trees are added to the mix.

“The first step in fixing the problem is to [identify] the compounds [in the air] and how they’re formed,” she says.

Benjamin Baldwin ’09 used a one-of-a-kind instrument Elrod built from scratch to focus his experiments on nighttime chemical processes, which can set the stage for particularly severe daytime smog. The instrument can isolate each individual chemical reaction for detailed study and is one of a handful being used in labs across the country, says Elrod.

“We pump in a little bit of the chemicals we’re actually studying, then flow all of that through a giant glass tube,” Baldwin explains. “By changing the conditions in the tube, we can measure how fast chemical reactions occur. If one chemical has a very fast rate constant, it could lead to lobbying to regulate that chemical. In Ohio, there are a lot of cases of children with asthma, which has been linked to ozone pollution. If we can understand those processes better, hopefully we can prevent its production.”

(Courtesy of Carl and Mary McDaniel)

(Courtesy of Carl and Mary McDaniel) Green Living in Oberlin

Carl and Mary McDaniels began construction on their East College Street home with clear objectives: to build a climate neutral home, to obtain LEED platinum certification, and to keep costs similar to that of quality conventional home construction. Along the way, they sought to avoid adding excessive construction waste to the landfill by recycling wood scraps into kindling and ground mulch, recycling cardboard and plastics, and rototilling more than 4,000 pounds of sheetrock into the soil. Of the 10,500 pounds of waste that was generated on their site, 10,000 pounds were reused and recycled.

When the home was completed in November, the McDaniels invited the community to share in their accomplishment.

Reddi Wall prepped for concrete

Cellulose (wall) foam insulation (roof)

Solar panel installation

PV inverter and meter

Saw dust recycled, winter wheat with straw cover

Sunken sun patio on south side

Carl, a member of the Class of 1964, is chair of the Oberlin College EnviroAlums and a visiting professor of environmental studies. —YGF

“Behold” Geoff Pingree, associate professor of English and cinema studies, was the grand prize winner of National Geographic’s World in Focus travel-photo contest. He took this photo in 2005 at the Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain, which was staging theatrical performances inspired by masterworks by Spanish artists. The photo, which shows performers playing King Philip IV and his second wife, Mariana of Austria, will be published in the January/February issue of Traveler. Pingree had stiff competition in the contest, as more than 4,000 amateur photographers submitted 14,647 images. His prize? A 15-day trip for two to Antarctica.(Courtesy of Geoff Pingree)

“Behold” Geoff Pingree, associate professor of English and cinema studies, was the grand prize winner of National Geographic’s World in Focus travel-photo contest. He took this photo in 2005 at the Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain, which was staging theatrical performances inspired by masterworks by Spanish artists. The photo, which shows performers playing King Philip IV and his second wife, Mariana of Austria, will be published in the January/February issue of Traveler. Pingree had stiff competition in the contest, as more than 4,000 amateur photographers submitted 14,647 images. His prize? A 15-day trip for two to Antarctica.(Courtesy of Geoff Pingree)

A FIELD of Poetry

For the past 40 years, FIELD has meant a lot of things to a lot of people.

For 2004 Pulitzer Prize-winner Franz Wright ’77, seeing his first published poems in FIELD “remains the single event that I am most grateful for and the most proud of. I can think of no other poetry journal that has done as much to encourage and cultivate the talents of younger poets by giving them the opportunity to see their works in print next to those of the finest and most famous poets in the country.”

For Timothy Kelly ’74, an accomplished poet who had two manuscripts chosen for publication—Stronger in 1999 and The Extremities last year—the honor helped bring about a personal resurgence. “The editors [of FIELD] believed in my work when I didn’t think that anyone but me really did,” he says. “I still read every issue.”

Equally affected are the staff and students who have helped to make FIELD: Contemporary Poems and Poets one of the longest-running poetry annuals published by a college. For their efforts, coeditors David Young and David Walker ’72 were awarded the 2008 Ohioana James P. Barry Award for Editorial Excellence. The award is presented to an Ohio-based serial that covers subjects of interest to the Ohioana Library, namely literature, history, culture, the arts, or the general humanities. In addition to editing for the Oberlin College Press, Young, who is skilled in five languages, has published 10 books of poetry since 1968, and Walker is the author, editor, or co-translator of five books.

Oberlin College Press started publishing FIELD in 1969. The FIELD Translation Series, which celebrated its 30th anniversary last year, followed. With 28 titles currently in publication, the series makes available the most exceptional of foreign writers to an English-speaking audience through the work of unusually gifted translators.

The year 1997 saw creation of the popular FIELD Poetry Prize, intended to recognize book-length poetry manuscripts. The press publishes the winning manuscripts annually as part of its FIELD Poetry Series. This spring, its 2009 edition will feature Dennis Hinrichsen’s Kurosawa’s Dog.

Pouring over the submissions—poems by professors, organic farmers, furniture makers, yoga teachers, professional gamblers, and more—are members of the FIELD editorial board, which consists of faculty members in Oberlin’s creative writing and English departments. They meet twice a month to discuss submissions and narrow their favorites to a select few for publication in the Poems and Poetics journal. These meetings have set the notoriously high standards for which the magazine is known. Former U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins has both praised the journal and lightheartedly noted how difficult it is to appear within its pages, Young fondly recalls.

But really, “it isn’t always so solemn and serious,” Young says of the work that he and others have done. “We take our jobs seriously, but we can laugh at ourselves too.” It’s the formula for success.

Franz Wright Reflects on FIELD

I was fortunate enough to be

an Oberlin student between January 1972 and June of 1977. I concentrated on English literature,

religion (under my beloved professor Thomas Frank) and philosophy—though

all the while I was also, and I suppose, primarily trying to learn how

to write under the guidance of David Young (my now lifelong friend/editor/improved

parent, &c .) My other significant teacher and friend was Stuart

Friebert, who helped me make translation part of that process. Without

teachers such as David and Stuart, for complex psychological reasons,

I very much doubt I would have been able to go on with my writing.

I became aware of FIELD as one of the major journals of contemporary poetry and poetics toward the end of my high school years in the Bay Area in California; and the fact that it emanated from Oberlin was my main motivation for applying to go to school there. Contact with FIELD seems to me now my most formative and fortunate influence. And it is impossible to overstate the excitement, pride and renewed determination I experienced as a result of publishing my first translations and poems in FIELD in the early and mid-seventies.

What continues to strike me as the most marvelous aspect of FIELD is the willingness—the foresight and courage, actually—on the part of editors such as Stuart, David, David Walker, Pamela Alexander, Martha Collins and others, to combine, in the pages of each issue, side by side, the newest works of established contemporary masters with the initial efforts of younger gifted and promising poets no one has yet heard of. I can think of no other poetry journal that has done as much to encourage and cultivate the talents of younger poets by giving them the opportunity to see their words in print next to those of the finest and most famous poets in the country. I can say personally that seeing my own first published poems in the pages of FIELD remains the single event that I am most grateful for and most proud of. This experience convinced me that I could and that I had to go on with the central ambition and wish of my life.

Typecast members presented a show on issues surrounding poverty to local children during Oberlin’s Poverty Symposium in September.(photo by John Seyfried)

Typecast members presented a show on issues surrounding poverty to local children during Oberlin’s Poverty Symposium in September.(photo by John Seyfried) Dramatic Changes in Health Education

The students at Oberlin’s Eastwood Elementary School lean forward and stare wide-eyed at a small stage down front. On it, puppets bounce about, humorously teaching their giggling audience about the dangers of alcohol, the benefits of making wise decisions, and how to be Good Samaritans. By the end of the performance, tiny hands are clapping wildly as the College student puppeteers—including theater majors and residential assistants—emerge from behind the curtain to greet their newfound fans.

The show, and others like it, is part of a new, fast-growing program offered by Oberlin’s Center for Leadership in Health Promotion (CLHP). Called Typecast, the program is a theater outreach initiative that educates community members from ages preschool through college about issues as diverse as alcohol and drug abuse, sexual health, and even trick-or-treating safety. Despite the fact that the center’s staff nearly doubled to 12 students in the past semester, assistant dean and director Lori Morgan Flood says, “right now we have more demand than we can meet.”

Typecast is based on the work of Sarah Frank ’09 and Alexa Punnamkuzhyil ’08, who four years ago offered a program called Our Whole Lives, a community-based sex education group for eighth and ninth graders. The program expanded, with Flood offering a private reading on interactive educational theater. Ultimately, her student employees started going into the local schools. “College students have the advantage of being more approachable than their teachers,” says Typecast member Cynthia Guggenheim ’09.

“We walk a fine line between having a serious skit and having something humorous, when appropriate,” says Flood, who is excited about the positive feedback she and her group have gotten, particularly since the traditional model used to get students interested in health matters seems to be waning.

“Our work is interactive theater,” says Chris Rice ’09, a long-time member of Typecast. “It’s not just about us preparing a skit and performing it. It’s about getting the students [talking].”