Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2008-09 Vol. 104 No. 2

Home Economics

(photo by John Seyfried)

(photo by John Seyfried)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

(photo by Michael Viancourt)

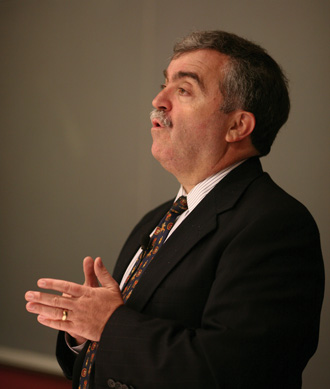

As the seats in King 106 fill up on a Thursday night in mid-September, Jim Rokakis ’77 hurtles down the stairs to the front of the classroom. He plunks a sign on an easel—the corners so bent with use that it hardly stands up straight. It’s a map of Ohio’s Cuyahoga County, where Rokakis is county treasurer. Thousands of red dots mark the locations of foreclosed properties.

Rokakis gazes at the Oberlin students for a minute, all the way up to the top row, where his wife, Laurie Shafer Rokakis ’78, sits. "I haven’t been in this room in 30 years," he says wonderingly. Then he explains his trajectory into city politics, which began when he was the same age as some of these students. He segues quickly into the subject they will tackle over the next four Thursday nights: the subprime mortgage meltdown and its genesis in places like Cleveland, the worst-hit community in the nation, where predatory loans have devastated entire neighborhoods.

Rokakis was one of the few people raising a red flag about these loans back in 2000. As early as 2006, he predicted the loss of trillions of dollars wrapped up in subprime mortgages, which would shake the foundations of the world’s economy. The Oberlin class is the third group he’s addressed this day about the crisis. He never looks at a single note.

"The subprime crisis is a profound turning point for our society and economy and culture," Rokakis says, pacing the front of the room with his arms wrapped tightly across his chest, his tie fluttering beneath one elbow. "You’re living in historic times. You’ll be talking about this for the rest of your lives."

Over the next four weeks, he will introduce the students to all the players in what might be the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression. He will track the bundling of bad loans into complex financial instruments sold all over the world—so complex that rating agencies didn’t understand them, buyers didn’t understand them, and even the sellers barely understood them. While apologizing for using a hackneyed metaphor, he discusses the perfect storm of factors that brought about this crisis: the starry-eyed notion that everyone should and could own a home. The lack of regulation that allowed both neighborhood con artists and cocky financial wizards on Wall Street to run wild. And greed —"greed on an industrial scale, greed of biblical proportions."

"It’s terrific to have practitioners like Jim come in to talk about their work," says Luis Fernandez, chair of the economics department. "Jim is showing students that you can take something very complicated and break it into little pieces. We can look at the beginning; we can see how it all happened. There are things we study in basic economics that are behind all of this. Moral hazard. Fraud. The effect of deregulation. People not paying attention to risk because they think other people will bear the losses."

People around the world now read about Jim Rokakis’s prescience in articles, blogs, and his own 2007 op-ed in the Washington Post. He is interviewed regularly (48 times and counting) by film crews from across the globe who are producing documentaries about the mortgage crisis. Ironically, Rokakis may be such a valued observer of this international crisis because his attention has been so fiercely local. He lives in the Cleveland suburb of Rocky River, just miles from the Archwood-Denison neighborhood where he grew up. He never took his eye off what was happening on the ground in ordinary neighborhoods that were so far from—yet so intricately and invisibly connected to—Wall Street.

"I don’t know if I’ve ever known anyone who loves the city of Cleveland the way Jim does," says Kathleen Engel, an expert on mortgage finance and regulation at Cleveland State University’s Marshall College of Law, who has worked with Rokakis on the mortgage issue. "He’s really become my hero."

Rokakis’s father tended sheep in his native Crete until four years before Jim’s birth, when poverty drove him to test the dream of emigration to America. He accumulated enough money to bring the rest of the family to the U.S. in 1955 and moved into public housing in Cleveland. Rokakis’s parents couldn’t drive or speak more than a few words of English, but they had a passion for community and politics. They passed this passion on to their son.

At Oberlin, the blue-collar Rokakis felt so intimidated that he never spoke a word in any of his classes. He majored in urban studies and wrote his senior thesis on housing courts, which push negligent absentee landlords to care for their properties. He made friends at Oberlin who likewise were interested in politics. They’d follow him back to Cleveland for weekends and eat his mother’s almond cookies while listening to him bemoan the decline of his neighborhood, where pristine shops and streets were starting to give way to urban blight. When Rokakis decided to make a run for Cleveland City Council, before he even graduated from Oberlin, several of these Oberlin friends—Mike Pauls, Rob Wollf, and David Krischer—supported him.

Rokakis might have been too shy to speak up in class, but he didn’t have a problem talking to his neighbors in Cleveland’s Ward 6. "When he started campaigning, I never saw anybody who was such a natural at it or had such a liking for endlessly banging on doors and talking to people," says Pauls ’79, who also hailed from Cleveland’s west side.

It became obvious to his Oberlin friends that he’d been talking to people in the neighborhood about politics all his life. "He already had a group of well-defined supporters in the ward," says Rob Wolff ’77. "A lot of young people from the neighborhood were very excited to work for him." What seemed like a long-shot bid became a good bet over the summer of 1977 as Rokakis and his friends campaigned and sat in on city council meetings to evaluate the entrenched councilman, Ted Sliwa. One day in late August, two bits of momentous news reached the campaign. Elvis had died, and Sliwa had dropped out of the race. Rokakis won the primary in October and was elected to city council in November. At age 22, he was its youngest-ever member.

His first term of office was tumultuous—both for him and for the city. Another young man also had just won election and was making headlines around the country. At 31, Dennis Kucinich was the youngest-ever mayor of Cleveland and throughout the nation. His two-year tenure was marked by jokes—City Hall was referred to as "Kiddie Hall"—and by high drama, as his administration clashed at one time or another with just about every business, civic and neighborhood leader, and group in the city.

"Those two years were like the last days of Salvador Allende, before he was overthrown by the CIA, when Allende was wearing a helmet and flak jacket and carrying a rifle through one crisis after another," Rokakis observes, his candor undiminished by the fact that his wife works for Congressman Kucinich. "Every morning, the news media would camp out at City Hall. There might not have been a news story at 9, but they figured there would be one by noon. They were never disappointed."

During those first two years, there was an attempted recall of Kucinich, who in turn attempted recalls of Rokakis and many other members of city council. The council president and a group of other councilmen were accused of taking payoffs from a carnival operator. Cleveland became the first major American city to go into default since the Great Depression. On top of these political and financial calamities, the city faced a court-ordered school desegregation order. As cross-town busing commenced in 1979, the exodus to the suburbs—white and black—accelerated, leaving the city in ever growing distress.

Rokakis survived that first fractious term in office and stayed another 17 years. He compares that time to a dog’s life, in which every year felt like seven. He focused much of his effort on neighborhood revitalization. He worked with residents to clear out "combat zones" of rowdy bars and porn shops. He helped to start and encourage the activities of community organizations. He pushed for the creation of a housing court.

By the late 1990s, Rokakis was discouraged with city politics and ready to quit when crisis hit Cuyahoga County’s treasury department. The then-treasurer had committed county funds to risky investments that ultimately cost the county $114 million—at that point, the largest percentage loss of public funds of any county in the country. People asked Rokakis to run for treasurer and restore sanity. He agreed and was elected to office in 1997.

"The office is narrowly defined as collecting tax dollars twice a year and investing them—not losing them, as the prior guy had done," Rokakis says. "But I knew there were things in state law that gave me openings to do other things, too." Taking advantage of those opportunities, he created innovative programs that help homeowners and neighborhoods. For these and other efforts, Rokakis received a national award for Smart Growth Achievement from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, American City & County magazine’s County Leader of the Year Award, and the 2007 Government Service Award from NeighborWorks America.

In 2000, a group of council members approached Rokakis with news that houses were being turned over—flipped—at a rapid rate in their wards. At its worst, houses changed hands two and three times a month. No one made improvements to the flipped properties, so their prices rose without any connection to their real values. When Rokakis began to study the situation, he found that county foreclosure rates had more than doubled in the previous five years, from 3,300 in 1995 to 7,000 in 2000.

So, he educated himself about what was happening. In neighborhoods throughout Cleveland, low-level mortgage brokers were doing everything they could to drum up business by arranging loans for people who could ill afford them. Many of these were so-called ninja loans, meaning the applicants had "no income, no jobs, and no assets." About half of the people getting loans were scammers out to flip houses; the other half were ordinary people who either didn’t understand how their payments would later skyrocket or were deceived about the terms of the loans. Rokakis found out that mortgage banks were actually paying the brokers a higher premium for loans that were the worst—and most likely to fail—for the home buyer.

Rokakis and others did everything they could to draw attention to this pattern of predatory lending. In 2001, they convinced the Federal Reserve Bank in Cleveland to hold a conference on the subject. Two hundred people gathered to discuss the problem, but the Fed declined to take action. Rokakis met with the FBI, the U.S. Postal Inspectors, and federal attorneys in Cleveland, trying to find an authority willing to intervene and prosecute what he believed were criminal activities. Someone in the U.S. Attorney’s Office asked him why they should prosecute. If there was a crime, who was the victim? "The banks were making these loans as quickly as possible and then selling them off to Wall Street," Rokakis says. "Who was the victim? The neighborhood was the victim. When I told them that, one of the attorneys rolled his eyes."

"The banks were making these loans as quickly as possible and then selling them off to Wall Street. Who was the victim? The neighborhood was the victim." (photo by Kevin Reeves)

"The banks were making these loans as quickly as possible and then selling them off to Wall Street. Who was the victim? The neighborhood was the victim." (photo by Kevin Reeves)

In 2002, Cleveland became the first city in the nation to pass an anti-predatory lending bill. Two other cities in Ohio quickly followed suit. Soon, lobbyists for the real estate industry, banks, and Wall Street firms descended on Columbus to protest these local laws. The Ohio state legislature passed a bill forbidding municipalities from enacting anti-predatory lending legislation, arguing that the state should take on this responsibility. Rokakis testified against the bill as the lobbyists looked on. "There was a wall of them," he said. "Eighty white males in $3,000 suits. They took up one whole side of the chamber."

It took the state legislature another four years to pass its own anti-predatory lending law in 2006. That year there were 13,500 foreclosures in Cuyahoga County.

Rokakis and others continued looking for solutions. The county launched the "Don’t Borrow Trouble" Foreclosure Prevention Program, which provides counseling to thousands of homeowners and has saved nearly 4,200 people from foreclosure since March 2006. More recently, Rokakis has worked to create land banks through which abandoned, tax-foreclosed properties transfer directly to the counties, thereby avoiding the sheriff auctions and eBay sales that contribute to more flipping.

"Some neighborhoods can’t be saved," Rokakis sighs. "With a land bank, we can decide how to use these properties for the benefit of the public. We’ll look at the next strategy for these communities. In some cases, that will mean assembling large blocks of land for the next stage of development in the city."

Rokakis continues to talk about the mortgage meltdown on the radio, at meetings of mayors and chambers of commerce, and on the streets, where people stop him to bemoan the ravaging of their beloved communities. He’s testified in front of Congress; the fourth time, in late October, he insisted on talking about the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) instead of the early warning signs of the current crisis, because he felt enough had been said about that.

"Some people were actually trying to say that we’re in trouble because CRA forces banks to make loans to poor people," Rokakis says. "But all CRA says is that banks have to make loans to underserved areas. They’ve done it very nicely since 1977. I testified that 87 percent of the loans that went bad were not even covered by CRA—they were done by non-depostitory banks."

At the end of Rokakis’s class in Oberlin, the next generation of urban saviors swarms around him. He has found them "amazing and insightful, as passionate and committed to issues of social justice as my generation." Eight students will go on to do internships at the land bank and the foreclosure prevention program. There, they will develop ground-level expertise as they help Rokakis clean up this mess.

Mikayla Lytton, a junior from Philadelphia who’s majoring in economics, plans to do an internship with the foreclosure prevention program. A self-described "typical Oberlin student who wants to save the world," she’d like to help people in danger of losing their homes understand and renegotiate their mortgage agreements. She’s impressed with Rokakis’s determination to keep speaking out for these people and with his willingness to keep speaking to people like her. "I ran into Jim at Gibson’s one night after class," she says. "He was eating his dinner, but he was more than willing to keep talking as long as I had questions."

Kris Ohlson is a freelance writer in Cleveland.