Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2009-10 Vol. 105 No. 2

Oberlin Writes

A not very definitive, somewhat idiosyncratic, and entirely unthematic glimpse of the strangely mighty literary output of a pretty small college in the middle of Ohio.

Want to write? Celebrated author Dan Chaon suggests reading.

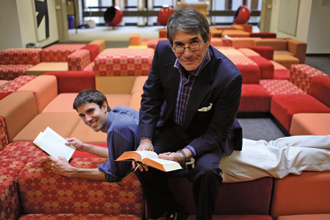

Professor Dan Chaon and writer Ishmael Beah ’04 before a New York City alumni event at the New York Society for Ethical Culture in the fall. (photo by Brad DeCecco ’96)

Professor Dan Chaon and writer Ishmael Beah ’04 before a New York City alumni event at the New York Society for Ethical Culture in the fall. (photo by Brad DeCecco ’96)

"It happens when you’re a kid—you sit with a book, and two hours later you lift your head and you haven’t been in your bedroom. There is some spark in the writing, in the scene, in the character, where it ceases to be words on a page, and you’re actually living in another place."

That, according to Dan Chaon, Oberlin’s Pauline Delaney Associate Professor of Creative Writing, is what makes good writing good.

He should know. Chaon holds a Pushcart Prize and an O. Henry Award, as well as the 2006 Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His second short story collection, Among the Missing, was a finalist for the 2001 National Book Award. His most recent novel, New York Times bestseller Await Your Reply, received glowing reviews in scores of national publications ranging from the Wall Street Journal to the Washington Post. It was named by the New York Times as one of the 100 Notable Books of 2009 and was included among critic Janet Maslin’s top 10 books of 2009.

But to creative writing students at Oberlin College, where he teaches, he’s none of that; he’s simply Professor Chaon. His own life’s work takes a back seat in the classroom, where the focus is on cultivating a student’s technique and fostering the development of his or her style.

So where does this seasoned wordsmith begin with a class of eager, green writers?

"I always approach creative writing through reading," he says. "Writers start out as readers; they start out loving books and wanting to emulate the experience that they got as a reader and to figure out how to do that themselves. So one of the important aspects of my class is that we’re always looking at a variety of different texts."

Chaon doesn’t assign specific texts in order to steer his students in one direction, but rather to allow each student to weigh his or her own voice, own method, and own mode of expression against that of an established other.

"I want creative writing students to find a voice that feels unique to them and that expresses some essential part of themselves," says Chaon. "As a result, I’ve had students who are primarily writing science fiction. I’ve had students who are writing very personal biography. I’ve had students writing realism. I’ve had students writing fantasy. And I’m not particularly concerned about the content of their work as long as it’s beautiful and has that personal spark that makes the work unique to them."

The ongoing quest to craft such a personal voice, Chaon emphasizes, is central to successful writing both in college and at the professional level. Such universal issues place Chaon and his students on equal footing in his creative writing workshop. Each week, Chaon plays host to a group of hungry writers—but instead of imparting the wisdom of a master, as a lecturer might do, he leads an exploration that prompts students to think critically about their peers’ work or their own.

"When you’re in a creative writing classroom, you are all writers and you are all looking at the same things. Whether you’ve been working at it for five years or 20, a lot of the same issues are still there in various forms," says Chaon. "I’m the guide, but we’re all sort of wandering out into the jungle."

Of course, putting himself on the same plane as his students can cause issues. In the workshop setting—where "everyone has an opinion, and everyone thinks that his or her opinion is equally valid"—there are times when Chaon must add weight to his own critique.

"It’s always nice to have the O. Henry Award beside you when you’re giving students feedback," he laughs.

Though about 25 students graduate from Oberlin with degrees in creative writing each year, Chaon acknowledges that many of them don’t pursue careers as authors. Still, the skills learned from studying narrative translate well across disciplines.

"Narrative is a way of thinking about the world. And it’s a complex way of thinking about the world—it’s valuable to be able to think in those terms as well as scientific terms or analytic terms or anything else," Chaon says. "The process of working with poetic concepts and narrative concepts is a very separate kind of thinking than, say, the kind of analytic thinking you do in an English class or the kind of mathematical or logical thinking you do in a chemistry class. Even if [my students] don’t become writers, they’ll still have skills that will serve them later in life.

"I’ve had students go into social work, and I think their training as writers sets a line to understanding people’s stories," he adds. "Wanting to feel compassion for people who other people don’t feel compassion for—that makes perfect sense to me."

Michael Emerson Dirda is a fellow in the Office of Communications at Oberlin.

Mentoring Writers:

An Oberlin Tradition

The Mentor and the Memorist

In A Long Way Gone Ishmael Beah ’04 tells the harrowing account of his childhood in Sierra Leone, in which he was forced to be a soldier in a brutal civil war. It was at Oberlin that he began to tell his difficult story.

OAM: Tell us about your experiences being mentored while at Oberlin.

Ishmael Beah: I had several mentors at Oberlin: Ben Schiff in the [politics] department, Laurie McMillin in my first-year rhetoric and composition writing class, Professor Yakubu Saaka from various African history classes I took with him, and Dan Chaon, who became the most influential teacher in my life at Oberlin. Professor Chaon was really responsible for unlocking the creative part of me and providing the necessary instructions, space, and discipline that I needed to write. We formed a friendship that is only possible at a place like Oberlin because of the size of the institution. The mentoring was built on honesty, respect, and a friendship that went beyond the classroom. In my case, this was particularly needed, based on the material I was working on.

When I finally decided to embark on the writing of A Long Way Gone, I asked Professor Chaon if he would be willing to delve into some very difficult and painful parts of my story. He casually agreed, but when I started writing about the horrors of the war, I could see how that affected him. But more importantly, I was moved by how he remained calm and didn’t allow any of the emotional content of the material to interfere with his honest and very helpful comments on my writing. That was meaningful to me and gave me the strength I needed to continue writing.

Ishmael Beah’s Top Five Influential Books

- Waiting for the Barbarians, J.M. Coetzee

- Anthills of the Savannah, Chinua Achebe

- The Farming of Bones, Edwidge Danticat

- The Devil that Danced on the Water: A Daughter’s Quest,

Aminatta Forna - Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The Playwright and the Professor

While the creative writing program at Oberlin has shown particular strength in mentoring students in its nearly 35 years as a stand-alone program, it’s not a new phenomenon. For playwright Thornton Wilder, who attended Oberlin from 1915 to 1917 then left—with great reluctance and at his father’s insistence—to attend and graduate from Yale, Oberlin Professor Charles Wager was central to his literary development.

In The Selected Letters of Thornton Wilder, Wilder writes about and to the professor many times. In fact, Wager, then chair of the English department, tops the list of why Wilder wished to stay at Oberlin, written in a 1917 letter to Wilder’s father.

"One [reason] is that there is no conviction stronger in me than when I sit under Prof. Wager, ‘it is good for me to be there.’" He compares his professor to four well-known Yale and Harvard professors: "I admit they may be brilliant and literary but they have not got that spiritual, almost ascetic, magnetism of Mr. Wager."

After leaving Oberlin, Wilder maintained a steady correspondence with his mentor, using words of such devotion and praise that modern readers may blush. "How many hours I sat under your rostrum," he wrote, "burning with awe and emotion, while you unfolded the masterpieces."

Dirda On Dirda

The New Michael Dirda Interviews the,

Uh, Earlier Michael Dirda

Michael Emerson Dirda and his father, Michael Damian Dirda (photo by John Seyfried)

Michael Emerson Dirda and his father, Michael Damian Dirda (photo by John Seyfried)

We asked May 2009 graduate Michael Emerson Dirda, a fellow in Oberlin’s communications office, to ask his dad, Washington Post book critic Michael Damian Dirda ’70, a few questions. The elder Dirda is the author of two collections of essays, Readings and Bound to Please; the memoir An Open Book; and, most recently, Book by Book: Notes on Reading and Life. In 1993 he received the Pulitzer Prize for his reviews and essays.

MED: First things first: How’s mom?

MDD: Still Oberlin Class of 1972, and still the greatest prints and drawings conservator in the world.

MED: What’s the distinction between a good writer and a great writer?

MDD: Good writers speak to their generation. Their books might be powerful or controversial or comforting, but they are fundamentally in tune with the times. Great writers tend to irritate and confuse us, at least initially. Their work seems strange, out of sync with an era’s accepted aesthetic standards—‘You call that a poem, Miss Dickinson? You call that a novel, Mr. Joyce?’ But wait a couple of decades, and the merely good books start to turn into period pieces. The great books keep surprising us.

MED: And what makes a great book critic?

MDD: A good critic makes us see better. He or she takes a book and shows us things we might have otherwise overlooked or missed. A great critic actually gives us new eyes. After William Empson wrote Seven Types of Ambiguity, people read poetry in a new way, with deeper understanding.

Me, I’m a reviewer and essayist, what I sometimes call a literary entertainer. My aim is to encourage people to read more widely, in general, and to point them, in particular, to the wonderful books of the past and of other countries.

MED: Your memoir was recently chosen to inaugurate the Lorain County Reads project, an expanded book club-type program designed to encourage reading and build community in Lorain County, Ohio. If you could choose one book that all Oberlin students would read for a similar program, what would it be?

MDD: That’s a toughie, but one good choice might be The Town That Started the Civil War, by Nat Brandt. It traces, quite thrillingly, the early history of Oberlin’s longstanding commitment to civil rights—one of the greatest of the college’s traditions.

MED: Nobel Prize-winning authorToni Morrison grew up in Lorain—also your hometown—just a few years before you. Is there something in the air that compels young Northeast Ohioans to become writers?

MDD: It’s not the air. It’s the Lake Erie water. In truth, nearly all writers are voracious readers when young. And small towns encourage reading—it’s a way of escape (In fact, escape is the great theme of Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson, who worked for a decade at a paint store in Elyria). If you’re a bookish kid and you love to read stories or poems, sooner or later you start to think of writing some.

MED: What book most shaped your life?

MDD: I can’t point to any single title. Your grandfather told me the story of Ulysses and the Cyclops when I was 5or 6, and soon afterwards I found a simplified version of The Odyssey at the library. Ulysses became my first hero: I wanted to be clever, have adventures, see the world. In junior high school I read Walden and even memorized long passages from it. Thoreau said it doesn’t matter what your family or society expect from you, what matters is that you become yourself. And here at Oberlin I took a French class, given by the late Vinio Rossi, on that great novel of love, jealousy, art, social class, and memory, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. I lived in that book for a semester, and it was the greatest reading experience of my college years.

MED: What do you think of the future of the book, given this generation’s preoccupation with all things digital?

MDD: I imagine that the printed book will eventually be replaced as people grow increasingly comfortable with reading on screens of one sort or another. I myself love physical books—to me, they really are what Keats called ‘magic casements’—but these familiar oblong objects are, in large part, only a delivery medium. Stories and poems will always be necessary to human beings, whether we access them on scrolls, pages, or screens. Indeed, art and narrative will evolve new forms along with the new technology. One danger, though, is the computer-user’s eagerness for speed and constant contact with others through e-mail, Facebook. and the like. It’s important to stress that true reading is solitary and always requires one to slow down: It’s an act of focused attention.

MED: Who or what is the single greatest literary product to come out of Oberlin College? And don’t say, ‘me.’

MDD: I’d probably pick the Field Translation Series, which has introduced readers to great poets from around the world, from Eugenio Montale and Anna Akhmatova to Gunter Eich and Miroslav Holub.

While writers as different as Thornton Wilder and William Goldman and Bruce Weigl and S.J. Rozan have been Oberlin students, I think the college’s greatest contribution to literature may be simply what it stands for—a liberal education, in the best sense, one that produces both artists and activists, people of commitment who live out their ideals. We can leave Oberlin, but Oberlin never leaves us.

Encyclopedia Brown and the

Case of the Rejected Manuscript

Writers who can wallpaper their small, sad apartments with rejection slips take note: Encyclopedia Brown, Boy Detective, by Donald J. Sobol ’48, was rejected by 26 publishers before it was finally accepted in 1963. Sobol, an award-winning, prolific, and commercially successful writer, subsequently wrote more than 65 books, including, in 2007, a new installment of Encyclopedia Brown.

Readers from the Rockies The Oberlin Alumni Club of Colorado has an Oberlin Authors Book Group that has met every other month for the last two years. Though the group sometimes exchanges e-mail with the authors in advance of the meeting, they were especially happy to have author Thomas Mullen ’96 join them by conference call to discuss The Last Town on Earth, which was named Best Debut Novel of 2006 by USA Today and won the James Fenimore Cooper Prize for excellence in historical fiction.

Oberlin’s Graphic Storytellers:

Drawn to It

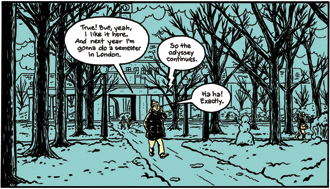

(the work of Josh Neufeld)

(the work of Josh Neufeld)

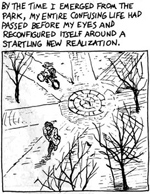

(the work of Alison Bechdel)

There are some careers that draw Obies like moths to a flame—and cartooning is one of them. The bewitching corona of the creative, often subversive and less-than-lucrative medium has led a series of talented alumni to immerse themselves in a profession that the art world and academia have long given the cold shoulder.

"As a child, I wanted to be a cartoonist, I knew that, but it got beaten out of me as I progressed through the education system," says Alison Bechdel ’81, author of the comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. After 25 years of chronicling the quotidian aspects of lesbian life, the strip was recently compiled into a well-received book, The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For.

Theorizing about why Oberlin is a crucible for so many cartoonists, Bechdel cites the "spirit of inquiry at Oberlin that does not accept the status quo as an answer." But David Heatley ’97, author of the raw, personal graphic memoir My Brain is Hanging Upside Down, which was recently translated into French, Spanish, and Dutch, has another hypothesis.

Oberlin’s "definitely a small petri dish of human experience," he says. "I wound up intensely studying human behavior while I was there. You need that to be a writer or a cartoonist."

That scrutiny lends itself to exploring political subjects, as well as personal ones, says Josh Neufeld ’89. The artist initially chronicled his adventures backpacking across Southeast Asia and Central Europe, but later used his pen to tell a story in which he was a peripheral figure rather than a protagonist. After volunteering in Biloxi, Mississippi, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Neufeld came across a 2006 Oberlin Alumni Magazine article about improvement efforts one year after the hurricane. In it, Kwame Webster ’10 discussed being uprooted from his New Orleans home at the start of his senior year of high school. Inspired by Webster’s story and that of six other New Orleanians who survived the flooding, Neufeld wrote the graphic novel A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge.

"Engagement with the real world and the idea of social justice and giving back somehow was a big part of my Oberlin education and something that stuck with me," Neufeld says. Writing A.D., he adds, was a way of doing just that; New Orleans residents thanked him for keeping the story of Katrina alive, "because they feel, with good reason, that a lot of the country has moved on."

Bechdel, Heatley, and Neufeld each took up graphic storytelling in part because it plays to their creative strengths, but the career appeals to them for other, separate reasons as well. For one thing, the medium is wildly versatile. "Anything in art history or design history is at your disposal," Heatley says. "It’s a really young art form, so there’s plenty of room for experimentation."

Bechdel says a linguistics class she took at Oberlin with professor Sanford Shepard was essential to the hodgepodge aesthetic that came to play a role in her work. "We would talk about cave painting, and Sufi poetry, and the surrealists, and ancient Greek texts," she recalls. "It was this mind-blowing sort of collage that we’d be exposed to in every class."

Neufeld found simply that comics were his chief passion. "Once I realized I wasn’t going to be a professional baseball player, comics was the default," he jokes.

Fans of Bechdel, Heatley, and Neufeld can take heart; each has a new project on the burner. Bechdel, in Love Life: A Case History, explores her relationship with her mother, as well as some of her young-adult romantic experiences. (Her previous graphic memoir, Fun Home, dealt with her relationship with her father, who passed away in her senior year.) Heatley is shopping around a collaborative project in which he illustrates writer Christen Clifford’s one-woman play BabyLove, the story of her sex life before, during, and after having a child. Neufeld is teaming up with Brooke Gladstone, host of NPR’s On the Media, to provide graphics for a book on the history of media called The Influencing Machine.

Josh Spiro covers start-ups and entrepreneurship for Inc. magazine in New York.

The Graphic Novel Groundbreaker:

While it’s hard to pinpoint the dawn of modern graphic storytelling, R.O. Blechman ’52 (originally Oscar Robert Blechman, in that order), was certainly there in the morning. Blechman’s adaptation of a medieval legend, The Juggler of Our Lady, an early example of the form, was published in 1953, the year after he graduated from Oberlin.

Blechman, whose Emmy Award-winning animation earned a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art and whose signature wobbly line has graced 19 New Yorker covers, published two new books this fall. Talking Lines: The Graphic Stories of R.O. Blechman collects work published and unpublished from throughout his half-century-plus career. Dear James: Letters to a Young Illustrator offers down-to-earth guidance for any up-and-comer in the arts and nicely illustrates Blechman’s own imagination: There is no James. The book was featured prominently in the New York Times Book Review’s year-end holiday books issue.

Myla the Muse

Celebrated novelist and essayist (and less-celebrated banjoist) Myla Goldberg ’93 is the only Obie we know of to be the subject of a song by the group The Decemberists, Song for Myla Goldberg.

The Text Book Case

Jennifer Morgan ’86 still shows up at a history class at Oberlin, even though the professor of social and cultural analysis at New York University graduated more than two decades ago. Morgan’s book Laboring Women: Gender and Reproduction in New World Slavery is used as a textbook in Gary Kornblith’s course, American History to 1877, where Morgan appears for discussion via videoconference.

Morgan says that once the book was finished she "harbored a fantasy that it would be taught at Oberlin.

"I was thrilled and stunned," she says, when Kornblith called to say he was teaching the book in his class.

"Students really enjoy the opportunity to talk with the author and to ask her questions about her post-Oberlin intellectual journey as well as about the book," says Kornblith.

Brilliance from the Other Lorain County College

One of the best-regarded poets among Oberlin alumni lives and works in the neighborhood, although it took some time for him to return. Bruce Weigl ’73, now a distinguished visiting professor at Lorain County Community College (LCCC), followed his Oberlin education with a number of faculty positions, eventually joining Penn State in 1986. In 1998 he returned to Ohio to teach at the community college. Taking the long way home isn’t unusual for Weigl. The Lorain native joined the army after high school and ended up in Vietnam, where he, paradoxically, suffered great loss and yet gained his literary voice. After the army he attended LCCC before a professor there encouraged him to transfer to Oberlin.

The author of more than a dozen books of poetry, Weigel has earned many distinctions: the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry, the Paterson Poetry Prize, the Poet’s Prize from the Academy of American Poets, the Cleveland Arts Prize, two Pushcart Prizes, a Pulitzer Prize nomination, fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Yaddo Foundation—and a Bronze Star for his military service.

Mystery Writer

Who’s Alan Furst?

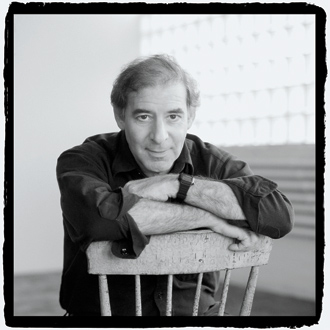

(photo by Shonna Valeska)

(photo by Shonna Valeska)

Alan Furst ’62 may be the most famous Oberlin alumnus you’ve never heard of. That’s because the critically acclaimed, best-selling author of 10 noir-tinted spy novels has kept a relatively low profile over the years, even as his books have developed a large, devoted cult following and sold more than 1 million copies worldwide.

Born and raised in Manhattan, Furst majored in English at Oberlin. After college, he worked as a Fulbright teaching fellow at the Faculté des Lettres at the University of Montpellier and then as a writer for a handful of magazines, penning travel articles, features, and book reviews for publications such as Esquire and the International Herald Tribune.

After writing several mystery novels in the 1970s and ’80s, Furst found his niche in a relatively untapped genre of fiction—an amalgam of historical fiction, spy novel, and noir—which he calls "historical espionage." His novels are set mostly in 1930s and ’40s Europe before and during World War II. Furst is known for his scrupulous research and historical accuracy and for creating a rich sense of atmosphere in his books.

His first historical espionage novel, Night Soldiers, was published in 1988, followed by Dark Star (1991), The Polish Officer (1995), The World at Night (1996), Red Gold (1999), Kingdom of Shadows (2000), Blood of Victory (2002), Dark Voyage (2004), The Foreign Correspondent (2006), and his latest, The Spies of Warsaw (2008). To say Furst’s books have been successful is an understatement. The media buzz surrounding them, for starters, has been nothing less than effusive.

The New York Times has written about Furst and his books more than a dozen times since 2001. In her Times review of The Spies of Warsaw, Alessandra Stanley wrote, "Furst’s tales … are infused with the melancholy romanticism of Casablanca. The New York Observer’s Laurel Berger called Furst "a master of the historical espionage thriller," and the Washington Post Book World described Furst as "a rarity, a writer of popular fiction who is also a serious novelist."

For more information on Alan Furst and his latest novel, The Spies of Warsaw, visit www.alanfurst.net

THE NEXT CHAPTER:

Some Writing of Your Own

If you think we’ve left out someone important, you’re right, from the obvious to the not-so-obvious (no Tracy Chevalier ’84? No Lois Beardslee ’76?). Please write and tell us whom you think we missed. We’ll run some of the comments in a future issue, or use them for future story ideas (in fact, we’re already planning longer features on some of the writers we’ve included in this issue). E-mail your comments and ideas to alummag@oberlin.edu with "Oberlin Writes" as the subject, or send mail to the Oberlin Alumni Magazine, 247 W. Lorain St., Suite C, Oberlin, OH 44074.

"The trouble with books is that they were all written by writers."

—William Goldman ’52

Goldman, a novelist and screenwriter, wrote Misery, Magic, Masquerade, Marathon Man, and Memoirs of an Invisible Man—and that’s just the M’s. Perhaps most famously he wrote the screenplay for All the President’s Men (and in the process coining the phrase "Follow the money") and the Academy Award-winning screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Goldman also wrote the book and screenplay The Princess Bride, which grew out of bedtime stories he told to daughters Jenny ’84 and Susanna ’87.

—JH

Letters of Transit

Sometimes the path to writing glory isn’t Oberlin’s famed creative writing program. Sometimes it’s the bio lab. John Wray (the pen name of John Henderson ’93) majored in biology, hoping to become an ornithologist. Instead he’s had to content himself with becoming a critically acclaimed writer of three books (in addition to being a finalist for several major prizes; in 2007 Granta magazine named him one of the best American novelists under 35)—and a bird-watcher. The ornithology thing didn’t work out. In his latest novel, Lowboy, Wray takes another unexpected route. Not only does half the action take place in the New York subway system, most of the book was written in the subway cars themselves. Getting "the look, smell, and feel of subterranean New York was crucial to the book’s success," he wrote. "It also happened to be cheaper than renting an office."

—JH

The Futures of Publishing?

While some people debate the future of publishing, the publishing company Flatmancrooked is selling it. Well, futures, really, and not in publishing, but in writers, beginning with novelist Emma Straub ’02. In the month following the September release of her first book, Fly-Over State, readers were invited to buy shares in Straub’s future for 10 bucks each, and in return, get a signed, numbered copy of the book, "plus my undying affection," she writes. If you write and let her know you bought a share, she’ll send you a thank you note that may even come with chocolate chip cookies. http://www.emmastraub.net.

—JH

The Late Bloomer

Helen Weaver ’52 isn’t exactly a late bloomer. Since graduating more than a half-century ago, she’s translated 50 books from French, including Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings, a finalist for the National Book Award in 1977. She also self-published the book Daisy Sutra: Conversations with My Dog, about animal communications. But her new book, The Awakener: A Memoir of Kerouac and the Fifties, her account of the time she spent with legendary Beat poet Jack Kerouac, "is the first book that is all mine to be published by a ‘real’ publisher," she says. That publisher is City Lights, the fabled San Francisco bookstore and publisher that gave the Beats their first refuge and recognition.

"City Lights is putting their all behind it. It’s their lead book for the season," says Weaver. "The first reviews have been wonderful, and I’m pretty excited to have such an interesting life at age 78!"

—JH

My Road to Self-Publishing

In early 2005, I took a four-month, unpaid leave from my day job to finish writing my novel. Signifying Nothing follows what happens when Lester Hobbs, a developmentally disabled man who has not spoken a word in his 19 years, begins shouting raps about life with his family. The book is really about the family’s other members, who are forced to make life adjustments because of Lester, before and after he begins to rap.

The novel completed, I queried 50 literary agents. A handful asked to see the whole novel; of those, a couple thought it was "obviously a quality manuscript" (to quote one) but didn’t think they could sell it in the current publishing climate. I then tried direct contact with editors and publishers—28 in all—with similar results.

I now had a decision to make. I could just forget the whole thing. I could spend possibly the rest of my life sending the book to this agent or that editor. (I was already in my mid-40s.) Or, instead of waiting for the publishing world’s elusive "Yes," I could say "Yes" to myself; i.e., I could self-publish. It is not always easy to decide that you’re right and the rest of the world is wrong. (Part of the difficulty is knowing that residents of mental institutions have made the same decision.) But in the end you either believe in what you’re doing or you don’t. I did, and to prove it, I handed $600 to the print-on-demand company iUniverse. Before I knew it, Signifying Nothing was available.

My book now had a cover, which would signify nothing indeed unless I got very busy putting the word out. So far, I have e-mailed everyone in my address book, started a Facebook account, gotten the book mentioned in the contributors’ notes for my freelance articles, sought out readings, and started a blog.

Part of the work for a self-published author is readying yourself for the responses you’ll get. Some people you tell about your project will offer a heartfelt, ‘Hey, that’s great!’ Others will give you a blank look, or, worse, a smile oozing with pity or embarrassment. I find it helpful to remember that the content and value of the book do not change with each person’s reaction to hearing about it. And it is the book itself that matters.

Besides, the stigma attached to self-publishing is showing signs of grave illness. Part of it is that the Internet has blurred the distinction between traditional publishing and the do-it-yourself kind. In the old days, self-published authors (a few of whom went on to success) sold their books out of the trunks of their cars; but with the availability of print-on-demand books through the Internet, a reader purchases my novel the same way she might buy The Da Vinci Code. Gradually, the question becomes not ‘Why did he publish it himself?’ but ‘Is it good?’

Clifford Thompson’s novel, Signifying Nothing, is available in paperback at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. He is the editor of the reference publication Current Biography. His blog is at www.tellcliff.com.

A Change of Heart

James McBride ’79 returns to Oberlin

James McBride hosted jam sessions with jazz students while at Oberlin

in October and found time to tour campus with his daughter, a high school senior. (photo by Ma’ayan Plaut ’10)

James McBride hosted jam sessions with jazz students while at Oberlin

in October and found time to tour campus with his daughter, a high school senior. (photo by Ma’ayan Plaut ’10)

It’s a Saturday afternoon in October 2009, and James McBride ’79 is heading up the aisle of an Oberlin lecture hall, having just wrapped up a two-hour talk on cinema and creativity to a full house of students and staff. Joining him on stage is Academy Award-winning film director Jonathan Demme, McBride’s longtime friend and the father of two current Oberlin students.

McBride, a saxophonist, composer, and author of two critically acclaimed novels and the best-selling memoir, The Color of Water: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother, carries his saxophone in one hand and greets a succession of admiring students with his other.

With his talk having run long, and another talk for the Friends of the Oberlin College Library just a few hours away, McBride is in a rush to get to his room at the Oberlin Inn. "Walk with me," he says, and proceeds to indulge this reporter in stories from his student days at Oberlin—where he studied music composition—and beyond.

"My relationship with Oberlin has evolved [over the years]," he says. "I spent many years never even thinking about Oberlin. Now I feel better about it. I’d like my children to come here. That says it all."

An award-winning musician who tours with a six-piece jazz and R&B band, McBride discovered his passion for jazz at an early age. Unfortunately, his enthusiasm wasn’t shared by many of his conservatory professors in the late 1970s.

"When I was here, the jazz studies program did not exist," he explains. "When I left Oberlin, I was a really well-prepared musician, despite the fact that the conservatory frowned on jazz. I had ambivalent feelings about the school."

Eventually, Oberlin embraced jazz as an art form (McBride says he could not be more excited about the new Litoff Building), and McBride warmed to his alma mater. In 1999, he delivered Oberlin’s spring convocation address. In 2005, he received a Distinguished Achievement Award from the Alumni Association. Most recently, in 2008, he was awarded an honorary doctor of music and humanities degree from Oberlin. That award, he says, "means one hell of a lot to me."

Outside the music world, McBride is best known for The Color of Water, which he wrote as "a way of shaking off the proverbial monkeys on my back." The book, which has sold more than 2 million copies since it was published in 1996, chronicles McBride’s quest to learn more about himself by uncovering his mother’s mysterious past. He’s since written two novels: The Miracle at St. Anna (a film version of the movie, directed by Spike Lee, was released into theaters in 2008), and Song Yet Sung, of which the Washington Post wrote, "McBride’s engagement with the historical continuum provides a new slant on an old subject"—the "old subject" being slavery and the Underground Railroad.

During the talk at Oberlin, Jonathan Demme showed audience members a clip from the classic 1948 Italian neo-realist film The Bicycle Thief, set in economically depressed post-World War II Rome. McBride explained that Demme once gave him a DVD of the film, a gift that helped inspire him to write The Miracle at St. Anna, which is about black soldiers in Italy during World War II.

"One [Oberlin] class I took in history changed my life, and changed my view of storytelling," he says. "You haven’t really lived until you’ve heard Geoffrey Blodgett lecture on Abraham Lincoln."

Wendell Logan, professor of jazz studies and African American music, also left a lasting impression on McBride.

"He never complained about racism," McBride says. "He didn’t let you complain about it either."

Elizabeth Weinstein, assistant director of alumni outreach and engagement at Oberlin, studied English and cinema studies at Oberlin. She’s written for the Columbus Dispatch, Northern Ohio Live, Ohio Magazine, Cleveland Jewish News, and, of course, OAM.

Editor's Note - Effective April 22, 2010: Since this article originally appeared, the Litoff Building has been renamed. Oberlin's new home for jazz studies, music history, and music theory is now the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building.

New Yorker Oberlin Writers

The New Yorker published poems by at least two Oberlin alumni this year. Learning to Read, by Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Franz Wright ’77, appeared in January, followed in October by First Leaf by Lia Purpura ’86. The New Yorker has one of the largest audiences a poet can reach and is considered the Holy Grail for many writers. This was the first time her work has appeared in its pages, so we asked Purpura, a writer-in-residence at Baltimore’s Loyola College, a few questions about the experience.

OAM: When did you start writing poetry?

Purpura: I’ve always written. I was one of those kids who scribbled—not really to any end, but because it felt natural and necessary to collect language: others’ funny sayings, interesting quotes, words I liked, character sketches, headlines, poems, thoughts for letters.

OAM: Can you describe what impact your Oberlin education had on your writing?

Purpura: I came to Oberlin for many reasons. I knew I wanted to be an English major, and I knew about Field magazine. And also because I played the oboe pretty seriously and wanted to be able to take lessons and play chamber music. I am endlessly indebted to my teachers—Stuart Friebert, David Walker, David Young, and Diane Vreuls—for creating the most spectacular climate imaginable for a young writer: generous, hugely challenging, and worldly. In fact, after graduate school at Iowa, I spent a Fulbright year in Warsaw, translating contemporary Polish poetry. It was an interest that was encouraged, even insisted upon, at Oberlin, and one that changed the scope of my life as a writer significantly.

OAM: There’s an expectation that poets are thoughtful and reserved. When your poem was published in the New Yorker, did you go out and spike a football in the end zone, or compose in your head a gloating letter to everyone who ever doubted you?

Purpura: For a poet, accustomed from an early age to very small audiences, the reach of the New Yorker was a strange, wild, and lovely thing. First Leaf is an autumn-centered poem, so it was really nice to hear from people that the piece spoke to those complicated fall sensations we all have of loss and beauty and insistence.

Both poets’ New Yorker poems can be found by searching that magazine’s website: www.newyorker.com.