Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2010-11 Vol. 106 No. 1

Family Ties,

School Ties

There’s a reason the Oberlin Alumni Association of African Ancestry reunion felt like a family reunion.

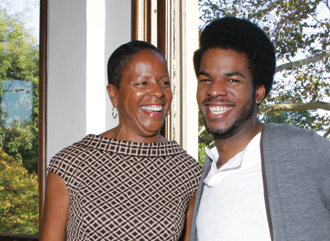

Jackie Bradley Hughes ’76 and her son, Jared Glenn ’07 (photo by Janine Bentivegna)

Jackie Bradley Hughes ’76 and her son, Jared Glenn ’07 (photo by Janine Bentivegna)

The first time Jackie Bradley Hughes ’76 brought her son, Jared Glenn ’07, to visit Oberlin, he was small enough to fit neatly on her lap. She had returned to campus to attend Commencement. Archbishop Desmond Tutu was the speaker, and she wasn’t about to miss such an occasion.

Later, the archbishop visited African Heritage House and spoke to a gathering there. As he talked, Jared stood on her lap and mimicked Tutu’s expansive gestures. At one point, he stopped speaking and pointed to Jared. Hughes, who is president-elect of the Oberlin Alumni Association, recalls Tutu saying, "Our children are always watching us. We need to remember that and set an example for them."

In that spirit, several alumni who returned to campus in October for the Oberlin Alumni Association of Afrikan Ancestry (OA4) reunion brought their children. A rising generation of potential Obies saw firsthand that there is a close African ancestry community within the larger Oberlin community; that these black alums are thriving and take an interest in their success; and that from one end of campus to another, many opportunities await students who choose Oberlin.

In fact, black alumni have brought their children to Oberlin for decades, proud of their own achievements and proud of the college’s commitment to social justice that led to the historic 1835 decision to admit people of color. It was a decision that would make a critical impact on the nation’s black intellectual life, especially since so many Oberlin grads went on to teach and influence new generations. Around 4,000 students of African ancestry have attended Oberlin and many had and have deep family connections to Oberlin. Some of these students were encouraged by alumni parents and other relatives who frequently discussed the joys and challenges of their own days at Oberlin.

"My mother used to take me to the Oberlin Alumni Club meetings in Indianapolis when I was so young I could barely walk," says Patricia Hummons Powell ’76. "She also took my brother and me to Oberlin reunions. It was really my first exposure to a college campus, and it formed my thinking about what the ideal college campus should look like—a place with beautiful trees, historic buildings, and a big square in the middle."

But Oberlin’s relationship with students of African ancestry hasn’t been a perfect one over the decades. During the nation’s long, ignoble Jim Crow period between 1876 and 1965, Oberlin faltered at times, even as it continued to admit black students.

Alumni like Powell can track some of the changes in attitude in her own family. Her mother, Dolores Johnson Hummons ’41, and her aunt, Helen Hummons Anderson ’26, were required to have black roommates or sometimes, in Anderson’s case, to live with black families in town. By the time Powell’s cousin Rosemary Davis entered Oberlin in 1956, students of African ancestry were assigned white roommates as first-years.

But "an unwritten rule of behavior among black students was that we did not congregate when we entered a room," Davis wrote in a collection of memories that Powell read at one of the reunion’s panel discussions. "The few of us on campus were scattered much of the time." Davis said that two of the dormitory housemothers were "insensitive and uncomfortable around us black students."

On the other hand, Davis recalled, Oberlin chose to do the right thing when confronted by blatant racism elsewhere. She, along with three white students, had been chosen to spend the spring semester as a participant in the Washington Semester Program at American University in Washington, D.C. Shortly before they were to leave, the college found out that the apartments where the students were to be housed wouldn’t allow African Americans. Oberlin called in the four students and told them that the college was withdrawing from the program because of this policy.

"I found the reactions of my white classmates to be very interesting," Davis wrote. "They were incredulous that this could happen to them. They had never experienced the slights and damaging consequences of segregation. They asked, ‘Does this happen to you frequently?’ One of my friends wrote about this experience as one of her most vivid memories in our 50th reunion book."

During the 1960s and ’70s, Oberlin rededicated itself to educating African Americans with efforts to recruit a diverse student body—in fact, Powell’s and Hughes’ class of 1976 had around 90 black students, the largest number of African heritage students ever. Of the more than 800 first-year students who began classes at Oberlin this fall, 25 percent are students of color. This makes the Class of 2014 the most diverse ever in terms of the percentage (though not overall number) of students entering.

But plenty of tension accompanied the transition during the ’60s and ’70s. Many black students felt there wasn’t a support infrastructure for them, especially for those who were the first in their family to go to college. Many students felt that some faculty and staff were racially insensitive.

"I’ll always remember that in one of my first classes in 1973, the professor said that race as an issue was water under the bridge," says Loreeta Earl, who went on to complete her senior year at the University of California at Berkeley, her hometown. "I was sitting there in my little Afro, shocked because Oberlin was supposed to be a very progressive place. I said, ‘Where are you coming up with this?’"

Plenty of the 130-plus attendees at the OA4 reunion experienced racial insensitivity and other frustrations at Oberlin, although some weren’t diverted by these things even when they were students. Herman Beavers ’81 came from a high school where white teachers told racist jokes in class and white students routinely chased him home. By the time he arrived at Oberlin, he was used to ignoring the unkind or ignorant things white people could say and was determined to succeed even though his high school hadn’t prepared him well for college life. "I let it go and opened myself up to the possibilities that Oberlin offered me, and I never looked back," he says.

When Beavers graduated four years later, he says, "I boo-hooed! It was a difficult place to leave, like a bubble, so radically different from anyplace else. When you go elsewhere, you can’t help but be disappointed."

Beavers did go elsewhere: to get a master’s degree in the writing program at Brown University, then a PhD in American studies at Yale—and Oberlin compared favorably. "These were places where people were content to let their surface attributes speak for them," Beavers says. "‘I’m so-and-so’s son; that’s what you need to know about me. I’m on the football team; that’s what you need to know about me.’ It became clear to me that the Ivy League schools were meant to sustain the status quo. Oberlin’s ethos is, no, we have to change the world, no matter how hard that is."

Some who returned for the OA4 reunion needed the passage of time to fully appreciate their years at Oberlin. Then there’s Andrea Hargrave ’97, who graduated and immediately became involved as a volunteer with the college. "I was exposed to so many different people and concepts and activities as an Oberlin student!" says Hargrave, who organized this year’s reunion of the OA4. "I took country line dancing, ballroom dancing. I expanded so much as a person. I believe in the mission of the college. If I don’t get involved, that leaves someone else to try to maintain the legacy. If it’s something I care about, I can’t wait for others to take care of it."

The 2010 Oberlin Alumni Association of African Ancestry reunion (photo by Tony Morrison)

The 2010 Oberlin Alumni Association of African Ancestry reunion (photo by Tony Morrison)

That spirit of engagement infused the OA4 gathering as a whole. Greg Grey ’82, who hadn’t been back to Oberlin since graduation, said he was drawn to the reunion by comments on OA4’s Facebook page. Newly inspired, he pledged to help recruit students below the Mason-Dixon line, where he grew up and now lives. "I stopped telling people in Atlanta that I went to college at Oberlin, because no one knew what I was talking about—I started telling them I went to Ohio State," he joked. "But now I realize that the college is only going to be able to do what we make it possible for it to do. It’s not about what Oberlin is going to do for us, but about what we’re going to do for Oberlin."

This spirit of engagement went beyond Oberlin, too. The OA4 alumni discussed other critical issues: the declining percentage of blacks going into the legal profession, the declining percentage overall of black students among the ranks of college students, the urgent need to reach out to the cohort of college-age black women—the largest such group in history. "When we look at kids who go to college, we look at their mother—the mother usually is the determining factor," Herman Beavers said in the morning panel. "These girls could have a transformative effect on the black community."

Pangela Dawson ’93 left the reunion newly energized not only to get more involved with Oberlin but also to convene a similar reunion for black alumni where she teaches, at the University of Kentucky. She hopes the OA4 gathering had a transformative effect on the cohort dearest to her: her two children, whom she brought to the reunion along with her husband. "I have such a sense of pride that I’m part of the Oberlin legacy," she says. "And I think my kids do, too. My son wore his Oberlin t-shirt to basketball practice the day we got back home."

Kristin Ohlson is the Cleveland-based author of the memoir Stalking the Divine and coauthor of Kabul Beauty School.

OA to the 4th for the 175th

Patricia Hummons Powell ’76, with a photograph of her mother, Dolores Johnson Hummons, and her mother’s college roommate, Quindolyn Rucker Washington at their 1941 graduation.

Patricia Hummons Powell ’76, with a photograph of her mother, Dolores Johnson Hummons, and her mother’s college roommate, Quindolyn Rucker Washington at their 1941 graduation.

Herman Beavers ’81 during

a panel discussion on the

legacy of Oberlin’s 1835

decision to admit

black students.

The OA4 reunion, celebrating 175 years of African American heritage at Oberlin, was a jam-packed weekend that included a dinner at Afrikan Heritage House, a performance of Macbeth (directed by Justin Emeka ’94), an alumni-student basketball game (the alumni won!), a panel discussion on the history of the Africana community at Oberlin, lunch with Dean Sean Decatur and students, a gala awards dinner, and a memorial tribute concert for Wendell Logan. Visit www.oberlin.edu/office/alumni/index.dot for a slideshow to see the weekend in pictures.