Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2013 Vol. 108 No. 1

MACARTHUR SPARKS

WHAT IT'S LIKE TO WIN A "GENIUS GRANT"

WELCOME TO THE CLUB, GENIUS: CLAIRE CHASE IS LATEST ALUMNI MACARTHUR WINNER

The same year she graduated from the conservatory, flutist Claire Chase '01 founded the revolutionary International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) in Chicago. A little more than a decade later, she's become a MacArthur Fellow, better known as a MacArthur genius.

As artistic director, Chase is redefining the concert environment and developing new audiences for contemporary classical music. In the changing economic climate, Chase is also intent on opening new avenues of artistic expression, as well as providing innovative music education programs to students in public schools whose music programs have been cut.

Now celebrating its 10th season, ICE tours internationally and is currently the Ensemble in Residence at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. With a flexible roster of 33 instrumentalists, ICE also presents series of concerts in New York, Washington, D.C., and Boston. Over the last decade ICE has premiered over 500 works and released acclaimed albums on the Bridge, Naxos, Tzadik, and New Focus labels. This year they will perform more than 65 concerts in 10 states and five countries.

Each year, the MacArthur Foundation of Chicago awards 20 to 30 "genius grants" — unrestricted fellowships to individuals "who have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits and a marked capacity for self-direction." The prize — a $500,000 stipend disbursed over five years — is designed to be "an investment in a person's originality, insight and potential." Oberlin boasts nine MacArthur recipients, including a 2012 winner (see sidebar), four of whom took part in a panel discussion in September during the launch of the Oberlin Illuminate campaign.

"I was sitting on an airplane in the middle seat in coach, and they were yelling at us to turn off our electronic devices when my phone rang," said Diane Meier '73, recounting her experience of winning the fellowship in 2008. "I didn't recognize the number, but I was curious — it was a Chicago area code, which is where I grew up. I thought I should answer it."

Although Meier could hardly hear over the noise of the plane, she understood the words "MacArthur" and "congratulations." "When I landed, I thought that I'd probably hallucinated the whole thing. But the number was there on my phone as proof."

Meier, who directs the Center for Advanced Palliative Care at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, was being honored for her 20 years of work in encouraging multidisciplinary approaches to relieving pain for people with chronic illnesses. The MacArthur, she said, allowed her to focus exclusively on the area that she felt needed her greatest attention: federal level policy change in support of palliative care.

"I would not have had the confidence … had this bolt from the blue not hit me," she said. "I thought, 'Somebody trusts my judgment, maybe I should trust my judgment.'"

Her peers have similar stories, each noting that the fellowship reshaped their careers in a singular major way—by encouraging them to take risks.

Ralf Hotchkiss '69 devoted his 1989 award to supporting his nonprofit organization, Whirlwind Wheelchair International (WWI), which develops wheelchairs for manufacture and use in developing countries. WWI has distributed more than 60,000 wheelchairs to needy individuals across the globe.

"I'd worked on wheelchair design as a hobby, yet I was never able to spend anywhere near the time I wanted to on it," says Hotchkiss, who is paraplegic and uses a wheelchair. With the MacArthur, "I knew that I could dive right in and nobody would call me on it."

I did not matter anymore, and I became a fantastic collaborator and facilitator. My work belongs to anyone. The grant gave me the freedom to do this.

Thylias Moss '89, a poet, artist, and professor of English at the University of Michigan, used her 1996 MacArthur Fellowship to share her work more broadly.

"What I loved about the MacArthur was that I was able to get out of the way," she said. "I did not matter anymore, and I became a fantastic collaborator and facilitator. My work belongs to anyone. The grant gave me the freedom to do this."

Richard Lenski '77, a microbial ecologist at Michigan State University, used his 1996 MacArthur to pursue "high-risk projects" he might not have otherwise. "The first thing I did was to take my family on an early sabbatical to Southern France," he said. "While I was there, the award gave me the freedom to go off in new directions."

Lenski is best known for leading a groundbreaking study tracking genetic changes in 12 initially identical populations of E.coli bacteria that started in 1988. He also studied scientific approaches to address the threat of anthrax after September 11.

These MacArthur "geniuses" say their experiences as undergraduates at Oberlin continue to play a role in their lives and careers, and they all cited teachers who inspired them.

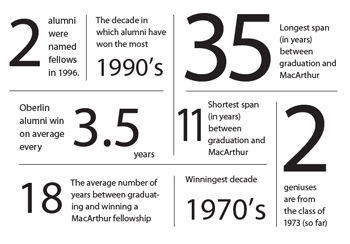

Waiting for the MacArthur call? Of course you are. 873 people have become MacArthur fellows since its 1981 inaugural class. Analyzing the data of Oberlin's winners (in a non-genius sort of way) might give you some hope that there's still time.

Waiting for the MacArthur call? Of course you are. 873 people have become MacArthur fellows since its 1981 inaugural class. Analyzing the data of Oberlin's winners (in a non-genius sort of way) might give you some hope that there's still time.

"What Oberlin gave me, which continues to be invaluable, was the courage to speak my mind," said Meier. "That was encouraged by all my teachers; it was valued here."

"I remember taking a mathematical biology class with Tom Sherman," added Lenski. "He stood at the chalkboard and derived a mathematical formula. Afterward, instead of talking, he just sat back and smiled at the elegance of it. Scientists look for crisp, valid ways of looking at the world. I remember that made a huge impression on me."

Hotchkiss remembered a physics class with Joe Palmieri that taught him how to apply his theories. "It was a whole different approach," he said. "We learned by doing things."

Moss said that her lowest grade as an Oberlin student, ironically, was in an English class. Her "low grade" (an A-) motivated her to become a professor.

"I knew I needed to concentrate on my weakness—that's why I became a professor of English," said Moss. "The MacArthur people would not have found me if not for that class." •