Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2014 Vol. 109 No. 1

Instructions for Publishing

an Article

about a

Conceptual Art Project

Written

by the

Organizers of the Project:

1. Have Nanette Yanuzzi and Ann Torke,

organizers of enact, write it.

2. Indicate that both authors are associate professors of art—Yanuzzi at Oberlin, Torke at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

3. Collect images from Art in the Mind, the conceptual art project created by

Athena Tacha, that inspired enact.

4. Combine images from both.

5. Print the following in the magazine:

It was 1970 when then-Oberlin art professor Athena Tacha created Art in the Mind, a collection of ideas, descriptions, drawings, and instructions submitted by 65 artists that was at once an exhibit, a catalog, and a work of art itself. Art in the Mind reflects a moment in the history of contemporary art-making when artists actively sought to engage culture, politics, and institutions through their work. The collection underscored ways in which ideas and language were becoming viable options as art.

If art could exceed the boundaries of conventional materials and venues, perhaps it could also affect—however tangentially—current socio-political discourse. Its pages include, for instance, correspondence between artist Don Celender and the head of NBC, in which the artist proposes that the hosts of the Today Show “dress in costumes to imitate famous paintings” for the next six years. (NBC declined.) The art of Bruce Nauman—typed instructions to drill holes into a tree and a mile into the earth and place microphones there—might be the activity he describes, the printed description itself, or simply the idea of doing it.

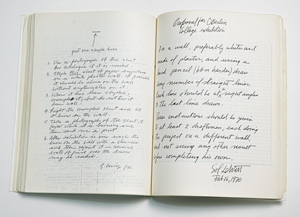

This set of handwritten instructions by artist Sol LeWitt was the only project of Art in the Mind that was actually carried out.

For 40 years, Art in the Mind was all but forgotten in the stacks of Oberlin’s Clarence Ward Art Library, until I [Nanette] tracked it down it for a colleague who was editing a book on conceptual art (and who was incredulous that the work was simply in the stacks; it is now in Oberlin’s Special Collections). Perusing the book’s slightly yellowed pages and unpolished layout, I was nevertheless captivated by its edgy content. I shared my discovery with Ann Torke, my former UC-San Diego grad school classmate [and coauthor of this article]. Through our lively conversations, we began recognizing the tremendous value of this “lost” document, which seemed to be the impetus for the genre of performance art. Many of the catalog’s contributing artists, like Vito Acconci, Victor Burden, and Adrian Piper, had developed international reputations as a result of this early “idea art.”

Inspired by this early document, we worked together to create enact, a virtual, internet-based art exhibition that expands upon the idea of conceptual art, in part to see if it still resonates for artists today.

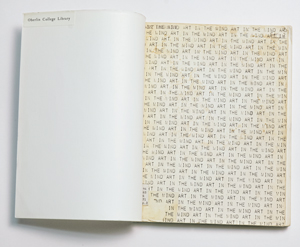

The cover of Art in the

Mind, with its title repeated

in Courier-font columns, designed by Athena Tacha.

The cover of Art in the

Mind, with its title repeated

in Courier-font columns, designed by Athena Tacha.

In curating enact, we invited artists who show a commitment to a conceptual framework for art, an active allegiance to critical interventions, or an understanding that dialogue and exchange can be primary motivations for art-making. Like Art in the Mind’s assertion that the exhibition and catalog were one in the same, we realized that enact should be a virtual document, in keeping with the values inherent in the original.

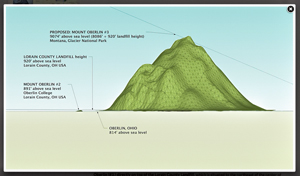

For enact, Lorelei Pepi’s “Mount Oberlins, Apology” proposes the creation of a hollow cast of Glacier Park’s Mount Oberlin; residents would be transported by hot-air balloons filled with methane gas produced by the Lorain County Landfill to this mountaintop, where they can apologize and then must walk down the mountain by foot.

As artists and former graduate students of a program formed in the 1970s and profoundly influenced by these ideas, we found conceptual art’s alternative approaches to art-making to be transformative, challenging long-held beliefs of what art is or can be. Like so much of the art that was occurring in California in the 1970s, steeped in experimentation and boundary crashing, the legacy of conceptual art continues today. It’s our belief that art and activism are not mutually exclusive. It’s this idea that provoked an immediate affinity with Art in the Mind; artists in that project used humor, philosophy, and critical theory to pose questions about society, culture, and art.

The year 1970 was a time of tumultuous social and political change. The civil rights movement and the women’s movement continued to make great strides in their struggles for political and social equality, and Vietnam War protests continued to be fervent and powerful.

It was the year when the National Guard opened fire on Kent State University antiwar protestors, killing four and wounding nine others. It was also the year when Oberlin College students Rod Singler and Cindy Stewart made the cover of Life magazine in an article titled “Co-ed Dorms: An Intimate Campus Revolution.”

Artists were asking hard questions relative to convention, the value of cultural production, and the conditions of institutional support, demanding accountability, transparency, and equal representation based on race, gender, and economics. Museums, galleries, and federal granting agencies all became fair game.

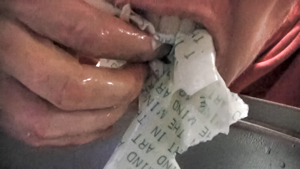

Enact An Act, a

video by Melissa Smedley

for the enact project,

includes the artist eating a copy of the original Art in

the Mind catalog

Enact An Act, a

video by Melissa Smedley

for the enact project,

includes the artist eating a copy of the original Art in

the Mind catalog

Part of what’s so interesting about Tacha’s Art in the Mind project is that it’s truly representative of a critically engaged discourse in the arts, one that’s alive and well in the Oberlin art department today.

Historian Ellen Johnson, a colleague and close personal friend of Tacha’s, was deeply involved in collecting the work of young artists at the time—many of whom would become extraordinarily important in their respective fields. Some of these artists also contributed to Art in the Mind, and several are part of the Allen Memorial Art Museum’s permanent collection.

Johnson also instituted the (still radical) art rental program, understanding that art, in all of its various forms, was an important component of a student’s education, regardless of major. The art rental program’s genius is the belief that art is part of everyday life, breaking down the hierarchy between public life and art by allowing students to borrow great works of art to hang in their dorms.

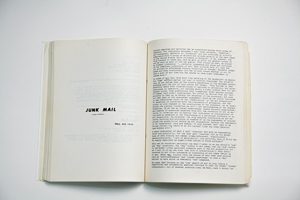

For Art in the Mind, Paul Kos proposed that a piece of paper marked “Junk Mail” be sent or hand-delivered to every resident of Oberlin. Joseph Kosuth explains it all in an essay from Art in the Mind, in which he says “At its most strict and radical extreme, the art I call conceptual is such because it is based on an inquiry into the nature of art.”

For Art in the Mind, Paul Kos proposed that a piece of paper marked “Junk Mail” be sent or hand-delivered to every resident of Oberlin. Joseph Kosuth explains it all in an essay from Art in the Mind, in which he says “At its most strict and radical extreme, the art I call conceptual is such because it is based on an inquiry into the nature of art.”

enact’s 61 contributions reveal a continued commitment to many of the philosophic and critical ideas that emerged during a transformative moment in U.S. history. In an age where the mechanisms of a networked economy continue to privilege commodity-driven aesthetics, artists and producers of culture are finding increasingly innovative ways to subvert, comment, and radicalize, despite (or because of) stealthy and ongoing efforts to coopt creativity.

The work selected for enact questions, disrupts, and reassembles. It empowers and suggests. Using video, sound, image, and the written word, it counters dominant narratives as much as it interacts with them. enact is a reminder that there continues to be great potential in art, and in artists’ desire to find solutions to some of the most complex problems of contemporary life. We invite you to spend some time with the exhibition—which also includes the original Athena Tacha project.

Visit enact-artinthemind.com to view works by artists such as Yanuzzi, Torke, Assistant Professor of Integrated Media Julie Christensen, Longman Professor of English David Young, and alumni Jen Liu ’98, Iz Oztat ’03, Kalan Sherrard ’09, and Georgia Wall ’08.

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.