Oberlin Alumni Magazine

Winter 2014 Vol. 108 No. 4

Thought Process

Hypothesis Bosch

When artist and Professor of Mathematics Robert Bosch interviewed for his position at Oberlin in 1990, his future colleague, Susan Colley, gave him a ride to the Cleveland airport. Susan’s infant daughter, Diane “Urchin” Colley, tagged along for the ride. Twenty years later, Urchin Colley ’13 became one of Bosch’s classroom and research students. Now they have coauthored the article “Figurative Mosaics from Flexible Truchet Tiles,” which was published in the Journal of Mathematics and the Arts in October. Sebastien Truchet was an 18th-century engineer and Carmelite cleric who discovered that square tiles divided diagonally into white and black halves could form an infinite number of pleasing patterns.

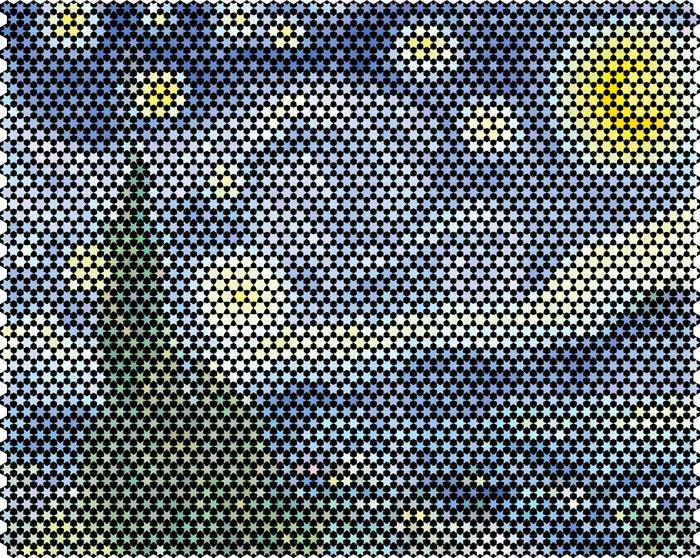

Bosch takes the practice a step forward by warping the diagonals in such a way as to create contrasts and depict a realistic image. Bosch has also deployed dominoes for his artwork, which includes large-scale portraits of Marilyn Monroe, President Obama, and Jean Truchet, as well as math-derived 3-D printed sculptures. This image, Bosch’s rendering of Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night, which uses a star-like variation on Truchet tiles and is thus called Starry Starry Night, is included in the journal article.

To see more of Bosch’s artwork, visit www.dominoartwork.com.

Pictured above: Starry Starry Night

Bechdel Stands Test of Time

In a 1985 strip from her comic Dykes to Watch Out For, Alison Bechdel ’81 had one of her characters explain her rule for what movies she sees. “I only go to a movie if it satisfies three basic requirements. One, it has to have at least two women in it… who, two, talk to each other about, three, something besides a man.” The rule has become known as the Bechdel Test, and it’s become an influential guide among feminists for evaluating film. In fact, a group of Swedish cinemas recently adopted the test for films they show as a way of drawing attention to the number of films that don’t pass it. Bechdel says she meets some young people who know her name only from this test, and not from her comic strip or books, which include the widely praised New York Times bestseller Fun Home.

Although Bechdel brought the concept to the masses (and, apparently, the Swedes), she credits her friend Liz Wallace for coming up with the rule. But Bechdel believes Wallace may have originally gotten the idea from Virginia Woolf.

“The Bechdel Test is really a boiled-down version of chapter five in A Room of One’s Own,” Bechdel says. In that 1926 work, which Bechdel read while at Oberlin, Woolf peruses a fictitious book and muses about how its two female characters are friends with one another and have interests beyond domesticity—a rarity for women in literature. “Suppose,” wrote Woolf, “that men were only represented in literature as the lovers of women, and were never the friends of men, soldiers, thinkers, dreamers; how few parts in the plays of Shakespeare could be allotted to them: how literature would suffer!”

Though at times she’s felt ambivalent about the way the test has been discussed in the media, Bechdel is now embracing the phenomenon. “After all,” she writes in a November post on her blog, dykestowatchoutfor.com, “the test is about something I have dedicated my career to: the representation of women who are subjects and not objects.”

O.B. Obies

November saw what might have been a record number of Oberlin alumni-related Off Broadway theater performances. Fun Home, based on the book by Alison Bechdel ‘81 and starring Judy Kuhn ’81, was produced at The Public. The Landing, with book and music by Greg Pierce ’00 and music by John Kander ’51, played at the Vineyard. Disaster!, cowritten by Seth Rudetsky ’88, played at St. Luke’s Theatre (closes February 28). Off-Off Broadway — and across the bridge — A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream, directed by Julie Taymor ’74, was being staged at the Theatre for a New Audience at Polonsky Shakespeare Center in Brooklyn (it closed January 12).

Musical Obies Worldwide

Musicians with Oberlin connections have grabbed two-fifths of the top Musical America Worldwide awards. Pianist Jeremy Denk ’90 was named instrumentalist of the year. International Contemporary Ensemble, formed at Oberlin and peopled with numerous alumni, won ensemble of the year. Musical America Worldwide has covered the performing arts industry for over a century.

Bookshelf

Love for Sale and Other Essays

Clifford Thompson ’85 Autumn House Press, 2013

This new collection of essays includes work that originally appeared in the Threepenny Review, the Iowa Review, Commonweal, Film Quarterly, Cineaste, Oxford American, and Black Issues Book Review. Thompson draws unexpected connections between the arts and between artists, finding commonality between Zadie Smith and Clint Eastwood and between Charles Mingus and Robert Altman, for instance. “With this selection,” critic Phillip Lopate writes, Thompson “vaults to the front ranks of essayists of his generation.” The author was among the winners of the 2013 Whiting Writers Awards, given to 10 emerging writers who show great promise (it includes a cash prize of $50,000). It appears that his decision to self-publish his first book, the novel Signifying Nothing, has paid off.

They Raised Me Up: A Black Single Mother and the Women Who Inspired Her

Carolyn Marie Wilkins ’73 University of Missouri Press

This memoir focuses on the many challenges the author faced when she moved to a gritty suburb of Boston to try to make it in the music world. But it also tells of the inspiration she gained from several ancestors who took similar paths before her.

The Continental Drift Controversy

Henry Frankel ’66 Cambridge University Press

If you’re familiar with the big debate between the fixists and the mobilists, you probably already have this four-volume work, published last year. The book earned its non-geologist author the Sue Tyler Friedman Medal for 2013 from the Geological Society London, but it’s safe for the general reader.

Slippery Rock

Mostly Other People Do the Killing, Featuring Moppa Elliot ’01 and Peter Evans ’03 Hot Cup Records

Jazz bands who care about traditions usually harken back a bit farther than the widely unloved smooth jazz of the 1970s and ‘80s. But the group, which the New Yorker recently put in league with the Lounge Lizards, has no guilt gleaning the era’s gilt.

Civil Disobedience: An American Tradition

Lewis Perry ’60 Yale University Press

The author, an emeritus history professor at St. Louis University, traces what he sees as the distinctly American tradition of civil disobedience back to 18th-century evangelicalism and republicanism and offers insights into modern movements that built on these movements.

Want to Respond?

Send us a letter-to-the-editor or leave a comment below. The comments section is to encourage lively discourse. Feel free to be spirited, but don't be abusive. The Oberlin Alumni Magazine reserves the right to delete posts it deems inappropriate.