Evelina Belden Paulson:

A Journal of Life at the Hiram House, A Cleveland Settlement, 1910

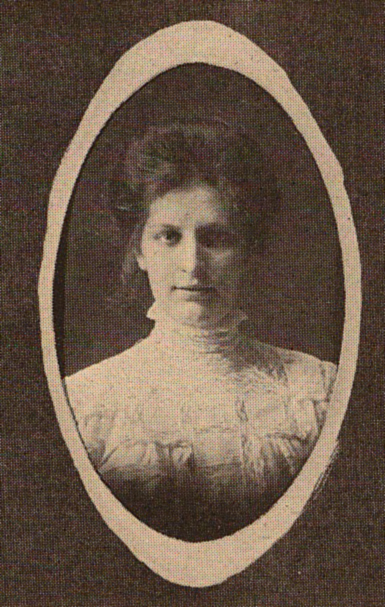

Eveline Paulson Belden at the time of her graduation in 1909

Collections: 30/319 Belden Family Papers

Authors:

Bailey James

Connor Jerzak

Elizabeth Manning

TRANSCRIPTIONS

- Document 1: Evelina Belden's Journal with annnotations, November 1909

- Document 2: Evelina Belden's Journal with annotations, 26 January 1909

- Document 3: Evelina Belden's Journal with annotations, March 1911

- Document 4: Evelina Belden's Journal, 1909-1910 (Full text, no annotation)

INTRODUCTION

Evelina Belden was born in 1885 in Bridgeton, New Jersey, and, like her mother, she attended Oberlin College. She graduated in 1909.1 For three years following her graduation, Belden worked for and lived in the Hiram House, a settlement house in Cleveland, Ohio, founded in 1896 by George A. Bellamy (1872-1960) as an extension of a student project he initiated during his time at Hiram College. The services the Hiram House provided for Cleveland's immigrant community were vast. Ten years after its founding, nearly 9,000 community members and residents were enrolled in programs across eleven Hiram House departments, including the Playground, Progress City, Cooking, Girls' Social Club Work, Sewing, and Camp Departments.2 At the time Evelina Belden arrived at the Hiram House in 1909, it primarily served the Jewish immigrant community, many of whom had fled the social and political upheaval in southern and Eastern Europe.3 By 1912, 148 non-resident volunteers worked at the settlement house, adding to a force of almost 40 resident workers, including Evelina Belden. According to its records, the Hiram House received an average of 250,000 visits per year from members and their guests. To meet the demands of an expanding operation, the Hiram House looked to the local and regional community, including notable philanthropists John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) and Samuel Mather (1851-1931), for financial support.4

Over the course of her life, Evelina Belden lived in five settlement houses, including the Hiram House, Chicago Commons, and Hull House.5 After leaving the Hiram House in 1912, Belden went to Chicago to investigate public dance halls, and later counseled boys held in the juvenile division of Cook County Jail, an undertaking that led to the formation of the first juvenile court in the United States.6 She also worked as a special agent for the Federal Children's Bureau in 1915 and served as an executive secretary in the American Red Cross Social Service Division in Poland after World War I.7 She married Henry T. Paulson in 1922, and together they had two children, Belden H. Paulson and Mary E. Paulson, both of whom also attended Oberlin College.8 In 1966, after having lived an extraordinary life, Evelina Belden Paulson died at the age of 81.9

Since her death in 1966, the Oberlin College Archives has housed Evelina Belden Paulson's student file and alumni information. From 2005 to 2009, her daughter, Mary Paulson Harrington ( b. 1923), and son, the historian Dr. Belden H. Paulson (b.1927), donated numerous family documents to the Archives. These included their mother's correspondence, reports, printed matter, newspaper clippings, and published journal articles and books. Taken together, the Oberlin Archives holds 14.4 linear feet of material on Belden Paulson and her family. Of particular note is an admiring article Belden Paulson wrote about her mentor and Hull House founder Jane Addams (1860-1935), as well as the journal Belden Paulson kept from her first year at the Hiram House, a unique document that is the core of this project.

Evelina Belden's Hiram House journal is of special interest in that it illustrates ways in which she, and, by extension, other middle-class women in settlement houses, grappled with the challenges and inconsistencies of living and working with the underprivileged. According to Jane Addams in her essay "The Subjective Necessity of Social Settlements," settlement houses provided educated white women the opportunity to live out their social ideals in an active way by helping the urban poor and vulnerable.10 Belden's journal, however, shows how these middle-class ideals of philanthropic service remained difficult to implement, as Belden often felt conflicted during her work. At times, Belden expressed disdain for the underprivileged boys she counseled, disgusted by their "dirty" looks, "garlicky" smells, and "distasteful" characters.11 Nevertheless, she attempted to overcome her discomfort by recalling the higher purpose of settlement houses. She urged herself to "feel the child's disposition behind the dirty exterior," reminding herself how "one should always be able to do that in a settlement."12 The first page of her diary appears to serve as a translation key, with Belden quoting colloquial sayings and then defining them for her later reference. In this way, Belden recognized her distance from the culture of the Hiram House visitors, even while she struggled against her own discomfort, all in an effort to reconcile her middle class upbringing and her work with the underprivileged.

Evelina Belden's journal also explores her feelings on the social value and limits of settlement houses. Belden's opinions on this subject reflect much of Jane Addams' writing on in "The Objective Value of a Social Settlement."13 The women agreed on many topics such as their shared critique of tenement houses and the cramped arrangements where many impoverished families lived. As Addams noted, "Back tenements flourish; many houses have no water supply save the faucet in the back yard; there are no fire escapes; the garbage and ashes are placed in wooden boxes which are fastened to the street pavements."14 Belden echoed this sentiment, writing in her journal: "One alley almost here has about six front-back doors for as many families and probably as many families again living upstairs. The children had absolutely no yard except that narrow alley."15 Belden and Addams both entered a cultural space foreign to them, perhaps without a full appreciation of what it meant to be poor in a city at the turn of the twentieth century. The pity both expressed in their writing with regards to the lives of the indigent further illustrates the tension between the middle-class background of most settlement workers and the impoverishment of immigrants and workers.

However, Evelina Belden is perhaps most interesting when she diverges from Jane Addams' line of thinking. Addams spent the majority of "The Objective Value of a Social Settlement" describing the ways in which Hull House helped the community that surrounds it. "The more of scholarship," she wrote, "the more of linguistic attainment, the more of beautiful surroundings a Settlement among them can command, the more it can do for them."16 Belden, on the other hand, had mixed feelings about settlement houses as organizations and worried that they were ineffective at truly helping people. "[The settlement house] does not go far enough in instilling real solid principles," she fretted amidst her entries on the best way to run the Games Room. "It doesn't do much more than keep the children away from a bad form of amusement and social life."17 Evelina Belden worked hard for the Hiram House community during her stay there, but she remained aware of the limits of settlement houses and the problems presented by her privileged status in a space intended for poor immigrants.

Evelina Belden's journal also highlighted changes in women's roles during the Progressive Era through her understanding of how education could affect human relationships to religion. These ideas are especially illuminating when juxtaposed to early feminist ideas about reason and education. Over a century before Evelina Belden began working for settlement homes, Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1798) argued that women only appeared vapid and without ability to reason because they were taught "corporeal accomplishments" instead of orderly thinking, skills reserved exclusively for male education.18 In 1910, Belden extended this idea further, applying it to the poor and underprivileged youth she mentored.

Evelina Belden articulated these feelings through her reaction to a Salvation Army meeting designed for the uneducated poor, comparing it to a traditional church service attended by wealthy citizens of Cleveland. At the Salvation Army service, she described herself as "critical and beyond the spell of its magnetic influence," even if this service "really did [them] good."19 Later, she recounted that the traditional church "appeal[ed] to the intellect and not the senses" and was "too far away [and] cold" to move the poor.20 Through these descriptions, Belden explained that her education allowed her to understand Christianity from a position of reason, not emotion. She felt distant from the spirituality promoted by the Salvation Army, but recognized its appeal to a different, less educated class. Thus, in an expansion of Wollstonecraft's idea that education for women would allow them to reason, Belden emphasized the ability of education to influence the way the poor interacted with the world.

This shift in focus, from the plight of women to the plight of the indigent, highlights the fin de siècle promotion of women's moral duties, including charity to the poor. As she committed herself to her all-consuming settlement work, Evelina Belden embraced these Progressive ideals. Her late marriage at age 38 indicates that, for her, at least early in her life, her duty as a charity worker took priority over her duty as a wife and mother, a shift that Wollstonecraft, who advocated women's education in order for women to become more capable wives and mothers, probably never imagined.21

Evelina Belden's settlement house work broke traditional gender roles in other ways as well. She worked as a brass hobbyist in her spare time, creating a candle shade out of brass and even holding classes for Hiram House residents on brass work.22 At the time, the only comparable classes were offered by men. These and other seemingly incongruous details indicate how Belden's Hiram House experiences defy simple characterization. As both progressive and deeply religious, educated but concerned for the uneducated, Evelina Belden's work embodied many of the tensions within the larger settlement movement.23 Despite these tensions and complexities, what remains clear is that Belden's varied work at the Hiram House facilitated her later diverse career as social scientist and distinguished social reformer.

[4] A Historical Report, 9, 105-109.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Harrington, "Obituary."

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Harrington, "Obituary."

[10] Jane Addams, "The Subjective Necessity for Social Settlements," in Twenty Years at Hull House with Autobiographical Notes, edited by Jane Addams, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1912), 113-128.

[11] Evelina Belden Paulson, unpublished journal for 1909-1910 (cited hereafter as Belden Paulson Journal), October 20, 1909; in Paulson Papers, OCA.

[12] Ibid, 10.

[13] Jane Addams, "The Objective Value of a Social Settlement," Swarthmore College Library, http://www.swarthmore.edu/library/peace/DG001-025/DG001JAddams/objvalue.pdf, originally published 1893.

[14] Ibid, 2.

[15] Belden Paulson Journal, January 26, 1910.

[16] Addams, "The Objective Value," 3.

[17] Belden Paulson Journal, 26 January 1910, p. 50.

[18] Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, (originally published 1792).

[19] Belden Paulson Journal, 12 March 1910, pp. 109-110.

[20] Belden Paulson Journal, 12 March 1910, p. 110.

[21] Wollstonecraft, Vindication.

[22] Belden Paulson Journal October 6, 1909, October 14, 1909; A Historical Report, 34.

[23] For an additional outline of these tensions, see Mina Carson, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1990), 198.