|

| Home :: Features :: The Roof That Jazz Is Raising The Roof That Jazz Is Raising By Marci Janas ’91

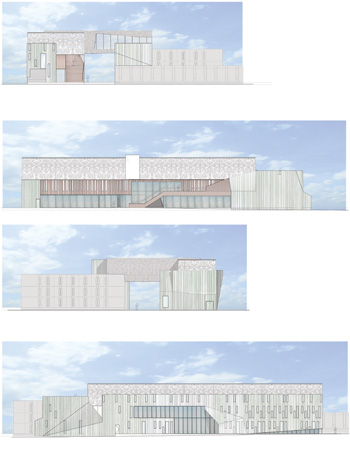

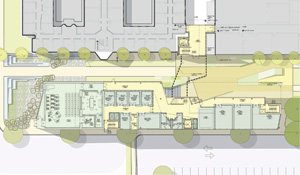

“A building should broadcast its purpose to the world,” says Paul Westlake, who leads the architectural team designing the Phyllis Litoff Building, a new home for jazz studies at Oberlin. With that in mind, Oberlin’s charge to his architectural firm, Westlake Reed Leskosky, was ambitious: craft a building to house jazz studies and the Conservatory’s academic programs in music history and music theory, a world-class recording studio, and the largest privately held jazz recording collection in the United States; integrate a dynamic architectural vision into the Conservatory’s interior and exterior geography; design the first music facility in the world to attain a gold LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) rating; and pay tribute to two remarkable individuals—the man who has personified jazz at Oberlin for the last 35 years, Wendell Logan, Professor of African American Music and Chair of the Jazz Studies Department, and the late Phyllis Litoff, beloved New York City jazz impresario, cofounder of the famed jazz club Sweet Basil, and philanthropic muse. “Under Wendell’s leadership, the Conservatory has become one of the world leaders in jazz education,” says David H. Stull, Dean of the Conservatory. “The jazz department retains a phenomenal faculty and a dynamic curriculum. This is undoubtedly the reason that we have drawn such an exceptional group of students, because it has certainly not been the existing facility.” [The jazz program is currently housed in Hales Gymnasium. —Ed.] “It is a great tribute to Wendell’s vision and his enormous personal investment that this program, its faculty, and its students are so highly regarded throughout the profession. This is the driving force behind the dream of creating a new home for jazz studies.” The genius behind the Westlake design is its integration of a powerful and innovative building with the Conservatory’s existing architecture and program. The Litoff Building will house the jazz department in an appropriate space, and its new offices supporting the music history and theory divisions will help reclaim the practice rooms in the Robertson wing and the second floor of the Bibbins building. This restoration will allow for the creation of new classrooms, studios, and chamber music rehearsal spaces, and will support a range of new programs and increase the number of practice rooms, providing a “a much-needed enhancement to our facility for both majors and non-majors,” says Stull. Form Following Function

“This is a building for playing music and learning about music,” says Westlake. “If you did not have a sign on this building—if there were no conventional, graphic means of announcing its purpose—you would know that this is a music building by its imagery.” After more than a year of discussions and meetings, Westlake Reed Leskosky’s design is as innovative as a sideman’s improvisation. Included are such startling riffs as a massive cantilevered roof, three stories high, that will hover in the air between the building and Robertson Hall, providing an iconic social space that Westlake calls “the soul of the Litoff Building.” Westlake envisions this shared realm—a lounge for the use of everyone at the Conservatory—as “a creative hub of thought, innovation, and creativity, an alluring magnet that will encourage social interaction.” Students, faculty, and staff will intersect here, taking advantage of its glass-walled westward views, wireless access, and caffeine-enhanced refreshment area—perfect for fueling late-night jam sessions. “This building is brilliantly conceived to reflect who we are and what we stand for at Oberlin,” says Stull. “It is about bringing all of us together and reflecting our dedication to the pursuit of great art, to harmony within our community, and the imperative need to steward our environment. It is highly innovative in its conception, which reflects the Conservatory’s approach to all of its endeavors.” Music from Oberlin The recording studio/performance space in the Litoff Building will be one of the finest of its kind in the nation. “Many recording facilities are designed to record a very small number of instruments at one time,” says Michael Lynn, Asso-ciate Dean for Technology and Facilities. “This studio will be large enough that it will offer a genuine acoustical environment and allow for high-quality recording of many types of music and many sizes of ensemble. The acoustics will also be adjustable to suit the particular musical situation.” The acoustical consultant for the Litoff Building is Dana Kirkegaard, of Kirkegaard Acoustic Design; his last Oberlin gig was the Kay Africa Memorial Organ in Finney Chapel. From this magnificent space, music, lectures, and contemporary media of peerless quality will be transmitted to the world. “Our vision is to harness the enormous resource of digital communication by streaming live performances and producing great recordings,” says Stull. “Through this medium we will be able to provide outreach to children, prospective students, alumni, and fans of serious music. With the advent of Oberlin Music, the Conservatory’s new recording label, we will be able to dramatically enhance the output and availability of music performed and created by our students and faculty. We will literally make the superb music of Oberlin accessible to the world.” The History of Jazz … at Oberlin

The love that James Neumann ’58 of Chicago has for jazz is manifest in a collection of more than 100,000 recordings and a vast array of posters, ephemera, and iconography. It is believed to be the largest privately held collection in the United States, and he and his wife, Susan, are giving it to Oberlin, where it will have pride of place in the Litoff Building. Jim Neumann was a 14-year-old science buff and self-proclaimed “baseball fanatic” growing up in Chicago, Illinois, when a neighbor who played guitar had him listen to a recording of Johnny Smith’s Moonlight in Vermont. It was the first jazz record Jim had ever heard, and he was hooked. “Nothing was better than that,” he says. “I gave up baseball quick.” A biology major at Oberlin, Jim was a mover and shaker in the Jazz Club, where he booked such acts as Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck, Woody Herman, Count Basie, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Duke Ellington, and Stan Kenton. A radio program of his on WOBC, “Jazz Hot and Cool,” allowed him to tape interviews with some of his idols. He began acquiring autographs, recordings, and memorabilia, simply because he loved everything to do with jazz. By the time he graduated from Oberlin, married, and joined his father’s Chicago business, New Metal Crafts, Inc. (a fine-lighting products manufacturer that rigged out all of the lighting at Disneyland Resort Paris), Jim’s avocation as a collector was established. Worldwide travels on behalf of New Metal Crafts (he is the company’s president) enabled him to “feed his love of jazz” and allowed him to live his dreams, scouting out hole-in-the-wall record shops in far-flung locales and adding such extremely rare items to his cache as the Swedish program for a 1939 Duke Ellington performance in Stockholm. A particular trove was a large collection of recordings impossible to obtain in the U.S. that Jim discovered in Genoa. The shop owner had protected his stock in underground caves during World War II. From 1977 to 1985, Jim and Susan were record producers. Bee Hive Records’ greatest claim to fame was a Grammy nomination for Johnny Hartman’s album Once in Every Life. Songs from the album were featured in the film The Bridges of Madison County. Jim’s first choice for a repository had always been Oberlin. “I wanted the collection to remain in the Midwest,” he says. “I’m proud to be a graduate of Oberlin … proud of Oberlin’s spirit, history, and the Conservatory’s great reputation. My hope for this collection at Oberlin is that it enhances the school as a center for scholarly work. If you want to understand the history of jazz performance, you’ll want to come to Oberlin.” The Jim and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection will be archived in a space specifically designed to protect it and to provide resources to digitally preserve it over time. “Listening to the definitive recordings by the great jazz artists is essential to a complete education,” says Stull. “This collection, in conjunction with digital access, will provide our students with an unparalleled resource dedicated to supporting their evolution as performers. The recordings will be available from anywhere on campus, including all of the spaces within the new building. This is an exceptional gift from Jim, and we are enormously grateful to be the beneficiaries of such an important collection.” Gold Standard

According to the web site of the U.S. Green Building Council, the LEED Green Building Rating SystemTM is the nationally accepted benchmark for the design, construction, and operation of high-performance green buildings. Given Oberlin’s environmentally responsible values and leadership, it was not difficult, says Westlake, to achieve a basic LEED threshold. A commitment to using good building practices—local and recycled building materials, carpets and paints that produce no off-gases, and occupancy sensors that will monitor ventilation demands—along with other mechanical and plumbing factors, put Oberlin at the silver level. But to go for the vaunted gold, a ranking few buildings achieve, is more than a challenge for Oberlin; it is a moral imperative. Doing so became a point of intrigue for the design team, as well. Research revealed that Oberlin’s substrate is ideally suited for the use of a closed-loop geothermal heating and cooling system. This extremely efficient system, in addition to being cost-effective, would effectively secure the building a gold LEED rating, the coveted A-plus on the U.S. Green Building Council’s report card. As an added value, using a geothermal radiant system reduces the need for ductwork, thereby reducing the need for penetrations in floors, ceilings, and walls that compromise acoustics. The environmentally responsible path is also the musically preferred path. How pitch-perfect. A Need For Support “The Oberlin Conservatory of Music is top-rated, and its jazz program is world class,” says Cleveland businessman Stewart Kohl ’77. In 2005, he and his wife, Donna, committed $5 million to Oberlin—the largest private gift in support of jazz education at a U.S. college—to support construction of the Litoff Building. “The Conservatory needs and deserves a physical home worthy of the outstanding faculty and brilliant young musicians that are its soul,” says Kohl. “Given the economics of higher education, especially in the musical arts, this simply can’t happen without significant alumni support.” A record donation from the Kulas Foundation soon followed the Kohls’ gift, as did two separate gifts of $1 million—from Joseph Clonick ’57 and from an anonymous donor. Friends of the project have made several other substantial gifts. The total project cost for the building, including specialized equipment for the recording studio, a number of new Steinway pianos, and an endowment, is projected at $22 million. “This is a time when we need everyone in our community—alumni, parents, friends, and supporters—to help us realize this dream,” says Stull. “This will be a flagship building for Oberlin and will provide a terrific resource for everyone. The Litoff Building represents the essential nature of Oberlin through its ingenious design and its reflection of our values. It is certainly worthy of great investment.” Editor's Note - Effective April 22, 2010: Since this article originally appeared, the Litoff Building has been renamed. Oberlin's new home for jazz studies, music history, and music theory is now the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building. |