An Enormous Gift and Responsibility

by Linda Shockley

In New Orleans, there seems to be a credo that if it's worth doing, it's worth doing with music. For Benjamin Jaffe, New Orleans born and bred, the credo holds an everyday application as he is the caretaker of Preservation Hall, which was founded by his parents in 1961.

Every evening, the line to Preservation Hall forms early down

St. Peter Street in the French Quarter of New Orleans. Although

the air is as heavy as a smoker's cough, folks don't mind the

wait because they can already hear the music through the open-shuttered

windows at the landmark structure. They know it won't be long

until they pass under the inauspicious wooden sign that reads

Preservation Hall, and enter the iron gates, grab a place on a

bench and catch the musicians live. This is real music. Traditional

New Orleans jazz. And the keeper of Preservation Hall is jazz

bassist Benjamin Jaffe '93.

Preservation Hall was founded in 1961 when tuba player Allan Jaffe and his wife Sandra converted a small art gallery into a concert hall where local retired and aging musicians could play. The formula was simple and it remains in place today:

-

Create a concert hall that is open nightly from 8 p.m. until midnight.

-

Don't serve food or drinks: only music.

-

Anyone of any age is welcome.

-

The sets will last approximately 35 minutes.

-

The admission charge is $5.

Jaffe

says that formula of presenting New Orleans jazz in a concert

hall was considered a revolutionary idea at the time. "This was

just before folk music hit it big, just after the founding of

the Newport Jazz Festival. New Orleans jazz was considered too

old-timey. And before 1968, while it was not uncommon for mixed

bands to perform in the North, it was still considered rare and

risky for blacks and whites to perform together especially in

front of mixed audiences."

Jaffe

says that formula of presenting New Orleans jazz in a concert

hall was considered a revolutionary idea at the time. "This was

just before folk music hit it big, just after the founding of

the Newport Jazz Festival. New Orleans jazz was considered too

old-timey. And before 1968, while it was not uncommon for mixed

bands to perform in the North, it was still considered rare and

risky for blacks and whites to perform together especially in

front of mixed audiences."

While many businesses stumble in the handing-off process from one generation to the next, Preservation Hall has continued to thrive and serve its mission under the younger Jaffe's care. A comfort factor plays a primary role in the ease of the transition. "I guess you tend to take music for granted if you grow up in this environment," Jaffe explains. "I was born and raised in the French Quarter. We didn't even own a car because it was a world into itself.

"I grew up knowing some of the great musicians. Many of them were in their 70s and 80s. While many of them weren't familiar names to the mainstream record-buying public, they were extremely influential in the development of New Orleans jazz: Chester Zardis, Sweet Emma Barrett, Billie and De De Pierce. These were people I got to hear several times a week. It's amazing to hear that every night. Now, in history books, they're studying people I knew."

Jaffe's work began and his education continued when, one single day after graduation, at age 22, he flew to Paris to meet the Preservation Hall Jazz Band. "I was exposed to so much new information, more styles of music, and spending time with musicians who encouraged me to experiment. I've carried that with me. He soon after returned to New Orleans to take over the management of Preservation Hall: his father had passed away; his brother Russell, who plays bass horn, was in law school; and his mother was in semi-retirement.

Jaffe adds, "When I returned to New Orleans, one of my primary challenges was to preserve the building and our musical archives. We've been in a restoration phase for a couple of years. Moisture in the South takes a toll on a structure in a very short time and the building was in a neglected state."

That restoration has included the addition of a first-floor office and the rebuilding of the second story, including a new porch and stairs. All new structural work in New Orleans must meet stringent historical code mandates for style, color and historically-appropriate materials.

"Preserving the archives has been another one of my primary objectives. My father collected audio, video, photographs, articles and interviews; his secretary was a librarian. We've spent seven years reorganizing. We're still in a bit of a transitional period as many older musicians have died and younger musicians are taking their places. The musicians now range in age from 30-60. People always asked my parents what will happen to the hall as the musicians pass away. I don't worry about it too much because this music is passed down along families. There's a strong tradition of apprenticeship in New Orleans. Every musician in New Orleans has family members who also play music. Music is part of the lifestyle. Here, the musicians aren't necessarily on the stage but on the streets. This dates back to the turn of the 20th-century.

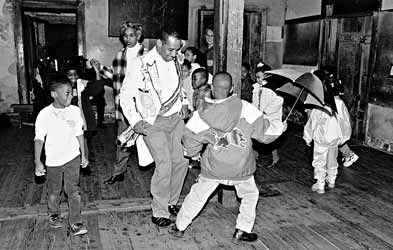

But running and maintaining the concert hall is only one aspect of Jaffe's work. He's also responsible for the national touring schedule of the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, which performs 120 concerts a year. He's responsible for the Preservation Hall recording collection. And he's responsible for the children's education program, which includes: the Gumbo Jazz Outreach program that tours 25 schools; the local program that opens the hall every Friday morning during the academic year, from 10 a.m. -12:30 p.m., to elementary school children; and offering performances and master classes for visiting school groups.

It was this education program that caused Jaffe to call upon his Obie roommate Ethan Graham '92, a psychology and music major who studied both classical and jazz. "When I returned I felt totally overwhelmed with the amount of work to be done," says Jaffe. "I thought Ethan would be the perfect person to continue the educational program and enhance it."

Following studies at Oberlin, Graham had received an M.A. in education from Tufts University, received his teaching certificate, and apprenticed at Shady Hill School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He also taught in Pittsburgh for a year before relocating to New Orleans to become education director at Preservation Hall.

"My challenge," says Graham, "in the outreach program is to keep it a New Orleans education. I came from a conservative, classical education the Gilman School in Baltimore and that lecture-based concept runs counter to the New Orleans mindset. The New Orleans audience is very different from outside audiences. Kids from New Orleans know the music and have uncles and aunts and parents who play it. When a group from Texas came to Preservation Hall, most the teachers and students sat passively in their seats. One teacher and her class was different; they were well behaved but they were bouncing up and down in the seats and totally with the music, which is more like the kids from New Orleans.

"I want the educational component to be fun. We combine music, story-telling, second line dancing, and parading to provide a history of New Orleans jazz. These kids leave feeling good. You can see the excitement on their faces when they march out that door."

Graham

says his time at Oberlin has served him well in New Orleans. "I

visited  Oberlin

twice when I was considering attendance there. I loved it so much

because the people were funky and offbeat. I realized that I had

a place among creative individuals at Oberlin. And like Oberlin,

New Orleans is filled with creative individuals, some of the most

insightful and sensitive people I've ever met. Success isn't defined

in the typical way. Oberlin and Preservation Hall help you define

success on your own terms, and to decide on what really matters."

Oberlin

twice when I was considering attendance there. I loved it so much

because the people were funky and offbeat. I realized that I had

a place among creative individuals at Oberlin. And like Oberlin,

New Orleans is filled with creative individuals, some of the most

insightful and sensitive people I've ever met. Success isn't defined

in the typical way. Oberlin and Preservation Hall help you define

success on your own terms, and to decide on what really matters."

Graham continues, "I remember wanting a definitive answer from Wendell Logan as to whether I was good enough and he said get in line with the rest of us. He warned us that there are no promises. He said it's a crap shoot and a struggle, where success is measured in growing creativity and exploration, not the status quo. It's still important for me to hear his voice."

Jaffe says, "I spent most of my time with Wendell Logan and I loved how he taught because his style was how I learned best. He introduced me to other musicians. He'd tell stories in the first person, just like the musicians from New Orleans. These are primary sources, not stories from books. He encouraged us to find the truth. He encouraged us to take risks. He took us to Cleveland, Elyria, Lorain. He dared us to learn what it means to be real artists.

"I always felt there were no limitations with Wendell. He doesn't push you; he expects you to show the initiative. And we did. I remember a group of jazz students spent three months booking a tour that included 20 performances, talking to assemblies and offering master classes at high schools in Atlanta, Birmingham and Columbus. There were seven of us in a cheap motel room cooking off hot plates. It was wonderful and exhausting."

And, says Jaffe, Logan isn't one to pontificate. "One of his former students sent a tape that was titled, 'Wendell Logan's Theory of Music.' We listened to it, fast-forwarded it, and it was blank from beginning to end. I loved that. Wendell taught that there shouldn't be any rules when it comes to learning or life. I remember calling him one day for encouragement after a particularly stressful day and he said, 'Well, you know Ben, calm waters never made for a skillful sailor.' "

Having said that, Jaffe sits back on the sofa in the office with the Preservation Hall cats, Little and Champ, and smiles.