Oberlin Women's Athletics in the Early Twentieth Century

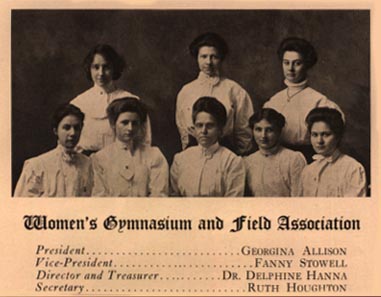

Women's physical education emerged for the first time in the mid-19th century. By the turn of turn of the century colleges were offering, and even requiring, athletics and other activities for their female students. However, far from developing physical education departments to parallel the athletic experience of male students, colleges shaped programs for women that would not disrupt contemporary gender roles and identities. Yet even within these confines, women were able to achieve a new level of independence and control unseen before. The effort of women to create a non-threatening program while simultaneously claiming control over their physical health is seen in the development of Oberlin College's Women's Gymnasium and Field Association(GFA), an association lasting from 1904 through 1926.

According to late nineteenth and early twentieth century medical professionals, women were the weaker sex, given to sudden bouts of sickness and overcome with frailty(Cahn 1994). These doctors saw physical exercise as a potential route to increased health and strength for women. However, any exercise was highly regulated for fear of doing damage to a woman and, in particular, to her reproductive system. Therefore athletics were limited to sports that did not involve excessive exertion or require a great deal of endurance. Sports which are extremely physical today were controlled by rules which limited movement. Thus, the GFA originally offered sports like tennis, skating and gymnastics. Basketball, when first offered in 1896, was played on a small court and did not include dribbling. While the GFA was able to encourage the development of athletic skill and endurance to some extent, annual reports continuously stress the importance of spirit and enthusiasm over athletic performance.

Athletics for women were further limited by another philosophy which, ironically, helped to create an opportunity to play in the first place. Educators such as Delphine Hanna saw physical education as an important component in creating a whole person. As Francis Hosford, Oberlin Professor Emeritus, wrote of Hanna's philosophy in 1923,

"It is increasingly evident that the purpose of physical training is not to make muscular marvels out of those already strong and active, but to give the body as well as the mind an education which will enable every individual to make the best use of all his powers in the business of life."

While educators viewed athletics for men and women within the context of this theory, the increase of men's intercollegiate sports in the early twentieth century shifted the emphasis from the holistic experience to winning. For women, however, this philosophy became the cornerstone of athletics for the next century, and still, to some extent is present today.

The GFA was an organization which aimed to increase the general well-being and happiness of its members through sport and social events. The goals of the GFA coincide with the physical education departments aims to,

"develop motor skills, endurance, strength, self control, and self confidence. The advanced course aims to develop a higher degree of muscular coordination, shorter coordination time, physical judgment, and such moral and social qualities as courage, presence of mind, decision, regard for authority, capacity for leadership, cooperation and self-sacrifice"(Leonard 1922).

These aims contrasted strongly with the philosophy behind men's athletics, listed in the same article as being designed teach men to "defend oneself effectively, to bear physical punishment coolly, and to react instantly to changing circumstances."

Therefore, the GFA sought to develop a well-rounded schedule of activities of both an athletic and social nature. In addition to offering intramural sports, the GFA held classes and lectures geared towards fulfillment of this goal. Classes, taught on subjects like proper attire and cooking, were held in equal importance as sports and seen as fulfilling a similar purpose. The GFA used athletics and social activities to develop an entire person, not to give women the opportunity to have fun with sports.

Dances and pageants furthered female students in their social development. The emphasis placed on these activities in annual reports indicates that these events were more important than sports. In the 1913-1914 school year, the pageant was seen by the board of the GFA as the biggest event of the year.

Within the theory of athletics as a route to holistic health, competition was viewed as damaging and counter-productive for women. Even though the GFA held intramural tournaments and encouraged female students to work hard to earn their varsity sweaters, Oberlin College treated women's athletics in such a way as to de-emphasize any level of competition or importance outside of self-development. Within the context of sports, Oberlin struggled to keep its female students ladylike and locked in to their proper roles.

In looking at old Hi-I-Hi's (the Oberlin yearbook) and Oberlin Reviews, a striking contrast is apparent between coverage of men's and women's sports. The Review devotes almost entire issues to men's athletic competitions. The Hi-O-Hi features four page spreads on each men's team, including photos of the teams in action. As for women, the Review occasionally mentions GFA meetings or events, but never discusses performance or results of games. The cover page of the women's athletic section in the Hi-O-Hi often depicts a highly feminized woman engaged in a low impact physical activity. Photos of the GFA board and different teams are included, but there are no action shots.

While the school's neglect to recognize the GFA may seem detrimental to the development of women's sports, it ultimately helped members of the association gain a new level of freedom. In a rigidly patriarchal world, the GFA offered these women a rare opportunity for autonomy. While they functioned within the confines of a preexisting idea of women and sports, women were the sole decision makers in the GFA. They elected each other on to the board, decided what sports and social events to offer, made their own budgeting decisions and controlled all other activities run through the association.

Members of the GFA, having no connection to Oberlin College other than their roles as faculty and students, were able to control every aspect of their organization. They determined the aims of the GFA and were able to decide how to achieve these goals without coming in conflict with men. While the GFA did not do much to question the existing societal perception of the relationship between women and sports, it provided a small group of women in the beginning of the twentieth century with an excellent opportunity to organize and increase participation of women in athletics.

back

to the begining

back

to my page

back

to the history 268 homepage