Our class will be broken up into two

sections, each guided by two seperate kinds of questions: (1) epistemological

questions, which

concern what, if anything, we can know, and (2) metaphysical

questions, which concern what there is. We began with Descartes'

Meditations, and his quest to find out what, if anything, does he know

with absolute certainty. We saw that he had an evil genius skeptical

hypothesis, and we have seen how he attempts to get out of this

skeptical worry. Related to Descartes' concerns in the Meditations, we

might also ask: to what extent does the limits of our

knowledge affect what there is, or what we think there is? To what

extent does what there is influence the limits of our knowledge? In

class, we'll discuss how one's metaphysics might be guided by

one's epistemology, or whether it might be the other way around. One

topic in philosophy where we can see these two sorts of worries--what

there is and our access to

what there is--influence or limit each other is by considering some

(baby) theories of perception.

Consider: you are reading with your eyes, on a computer screen or a print-out of this webpage, these black words on a non-black background. Perhaps you are simultaneously listening to your ipod or hearing the hum of the computer or listening to people jabbering in the background. Maybe you smell the ink of freshly printed paper or the after-stench of onions you had for lunch or someone's fruity gum or perfume. You are also having some sort of tactile sensations right now, like the feel of paper in your hands, or the firm contact of a desk chair or a couch or a barstool. And so on. You are have various sensations with (what you take) to be the outside world around you. You are like a bigger and better roomba, navigating around stuff in the world, taking it all in through your various sensory organs. Or so you might at first think...

How do your sensory organs work? How is it that you have access to the outside world? Are colors and sounds and tastes and textures and shapes--those things that you seem to attribute to objects out in the world--are they really out there in world? If you give yourself some time to think about it, this is what you might come up with:

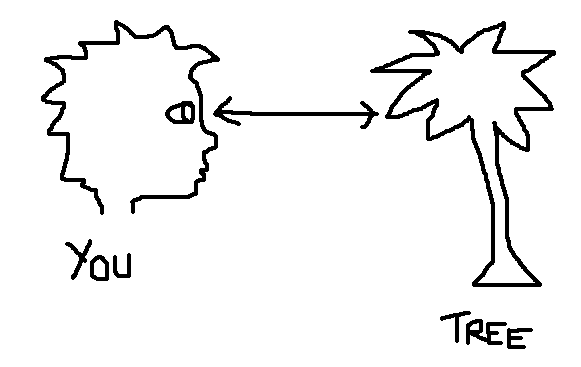

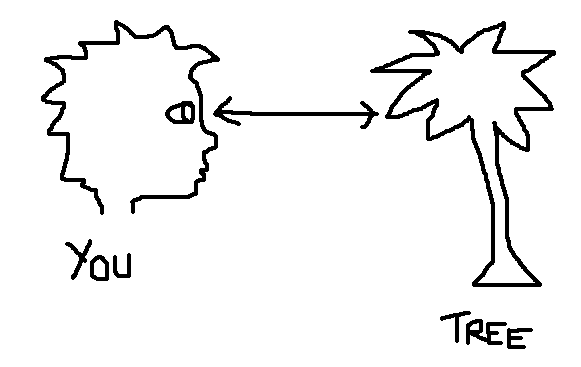

"There is me, a human, and the rest of the world, which I detect directly through my sensory organs. The rest of the world is independent from me; if I were to disappear, the rest of the world would still be here, and it would remain as I thought it was. Why do I have the sensation of seeing typed words right now? Because there are typed words in front of me now. Consider the following diagram for clarification:

(Not drawn to scale)

However, this view has several problems, which we went over in class, and which I will summarize briefly here:

(1) The relationship between external objects and ideas is incomprehensible. What sort of relationship would make sense in any case? How could we make sense of the relationship between external objects and our ideas? You might think that our ideas resemble or are simlar to or are like the external objects. Consider: How does a picture, a portrait, say, get to be about a particular somone? Well, first, the picture has to be like or resemble or be similar to the individual. In the above drawing, for example, I tried to show this by having the tree idea (the tree inside of the thought bubble) be somewhat similar to the external, mind-independent tree (the tree in front of the spikey-haired dude). But if this is right--if ideas get to represent or be about external things by being similar to them in the right sorts of way--then we run into a problem: we are only justified in thinking that two things are similar if we have experienced them both. If indirect realism is right, however, how do we know that our ideas are similar to external objects? According to this picture, the only access we have to external objects is by our ideas that we have of them. So we have no way to get at the external objects in order to confirm that these things are indeed similar to our ideas of them. It would be like claiming that a certain portrait represents a particular individual, Bob, who no one has actually ever seen. If no one has actually seen Bob, then how do we know that the picture looks like him at all? So the relation between external objects and ideas can't be one of similarity. But what other options are there? None that are coherent, says this line of argument.

(2) The veil of perception. Similar to the last objection, this one claims that there is, according to indirect realism, a perpetual veil of perception between us and things in the external world. We can never get at things directly, in other words, so how can we be sure that these things are even there? One answer might be: well, that there are external objects that are similar enough to our ideas is simply the best explanation for why we have the ideas that we do. Remember our explanation of the view: "why do I have the sensation of seeing typed words right now? Because there are typed words in front of me now, and they are causing me to have an idea of typed words. It is through this idea, then, that I have access to the typed words that exist out in the world." In response to this objection, however, is the following: the indirect realist has to at least admit that there are somtimes ideas that are not caused or connected to external objects. Just think of all the things that led the indirect realist to be an indirect realist in the first place--dreams, hallucinations, illusions, etc. Since the existence of external, mind-independent objects doesn't help explain why we have the ideas we do in these sorts of cases, why should we think it's any better of an explanation in other types of cases. Finally, just try to say--fill in the gritty details, that is--how it could be that an external, mind-independent thing causes or affects a mind-dependent idea. It's incoherent!

(3) Inconceivability Argument. Try to imagine something without imagining that you are there perceiving it. Go ahead. It's impossible. Everytime you try to imagine something, you have to imagine that you are looking in on the thing you've imagined--perceiving it from above, so to speak. This (supposedly) shows that objects do not exist independent of minds or ideas. [Incidentally, there's a problem with this argument. What is it?]

(4) Variability Argument. Recall problem (2) for Direct Realism: "What may look one way to you may look another way to another. Moreover, what may look one way to you at one time, may look another way to you at another. Colors, tastes, smells, feels, etc., can all vary from observer to observer, and can vary in the same observer at different times. If this is right, then which perspective is privledge? And how do we account, on the naive view, for the fact that some people have got it wrong, if there is such a priveledged perspective?" Notice that this isn't just a problem for colors, tastes, smells, etc., but it also seems to be the same with shapes, extension, texture, solidity, motion, etc. What may look smooth far away, may look jagged close-up; what is small far away may be large close-up; what is oblong from one perspective, can be perfectly round from another; what moves fast to one, can move slow to another, etc. In other words, it seems that all properties can vary from observer to observer, or from one time to another in the same observer. But if this is right, and if none of these perspectives is privledged, then what's left for external objects to be?

So, to accommodate the above sorts of objects, we might modify our Theory of Perception to the following...

So, on this view, things would 'disappear' if there weren't any mind to perceive it. Although this is sort of the wrong way of looking at it, since there are no objects 'out there' to disappear. Moreover, if there is a mind that perceives everything all of the time--perhaps God, say--then things wouldn't 'disappear' in any sense.

However, you might wonder whether, like direct realism, idealism can make any sense of the distinction between 'veridical' ideas and 'illusory' ones. Even the idealist has to admit that certain ideas, such as the one of you reading a string of words right now, are more vivid, steady, distinct, and orderly, than other ideas, such as the one you have when you have the idea of a watery image on hot asphalt. Also, some ideas are voluntary (as when you purposely look at the sun and then look away and see an orangey-red after image), while others are involuntary (as when you are reading the flow of these typed words right now). Can there be a distinction, then, on this view between 'dreams' and 'reality', for example?

Discussion pending...

Note: The summary above is very quick, dirty, and incomplete. For elaboration, and a more accurate representation of the views I've outlined, see the following helpful internet resources:

Consider: you are reading with your eyes, on a computer screen or a print-out of this webpage, these black words on a non-black background. Perhaps you are simultaneously listening to your ipod or hearing the hum of the computer or listening to people jabbering in the background. Maybe you smell the ink of freshly printed paper or the after-stench of onions you had for lunch or someone's fruity gum or perfume. You are also having some sort of tactile sensations right now, like the feel of paper in your hands, or the firm contact of a desk chair or a couch or a barstool. And so on. You are have various sensations with (what you take) to be the outside world around you. You are like a bigger and better roomba, navigating around stuff in the world, taking it all in through your various sensory organs. Or so you might at first think...

How do your sensory organs work? How is it that you have access to the outside world? Are colors and sounds and tastes and textures and shapes--those things that you seem to attribute to objects out in the world--are they really out there in world? If you give yourself some time to think about it, this is what you might come up with:

- The Naive Theory of Perception (A.K.A: Direct Realism)

"There is me, a human, and the rest of the world, which I detect directly through my sensory organs. The rest of the world is independent from me; if I were to disappear, the rest of the world would still be here, and it would remain as I thought it was. Why do I have the sensation of seeing typed words right now? Because there are typed words in front of me now. Consider the following diagram for clarification:

(Not drawn to scale)

On this view, external objects are

mind-independent, and we have direct access to them via our sensory

organs. Simple."

However, this view has several problems, which we will go over in detail in class, and which I will summarize briefly here:

(1) In the meditations, Descartes pointed out that the senses sometimes deceive. There are illusions, hallucinations, etc. It would seem silly to deny this. Just place a pencil half-way in a glass of water or waggle that same pencil between your thumb and forefinger, simultaneously moving your hand up and down. In each case, the pencil will look bent, even though it isn't. But the above naive picture has no room for such perceptual deceptions. Put another way: if we perceive things directly, then how can we ever explain misperception?

(2) There is perceptual relativity and variability. What may look one way to you may look another way to another. Moreover, what may look one way to you at one time, may look another way to you at another. Colors, tastes, smells, feels, etc., can all vary from observer to observer, and can vary in the same observer at different times. If this is right, then which perspective is privledge? And how do we account, on the naive view, for the fact that some people have got it wrong, if there is a priveledged perspective?

(3) Finally, in light of (1) and (2), how do we know for sure that there are these mind-independent objects out there?

So, to accommodate the above sorts of objects, we might modify our Theory of Perception to the following...

"There's me, and the rest of the world, which I detect indirectly through my sensory organs. The rest of the world is independent from me; if I were to disappear, the rest of the world would still be here, and it would remain roughly as I thought it was. So why do I have the sensation of seeing typed words right now? Because there are typed words in front of me now, and they are causing me to have an idea of typed words. It is through this idea, then, that I have access to the typed words that exist out in the world. Consider the following diagram for clarification:

However, this view has several problems, which we will go over in detail in class, and which I will summarize briefly here:

(1) In the meditations, Descartes pointed out that the senses sometimes deceive. There are illusions, hallucinations, etc. It would seem silly to deny this. Just place a pencil half-way in a glass of water or waggle that same pencil between your thumb and forefinger, simultaneously moving your hand up and down. In each case, the pencil will look bent, even though it isn't. But the above naive picture has no room for such perceptual deceptions. Put another way: if we perceive things directly, then how can we ever explain misperception?

(2) There is perceptual relativity and variability. What may look one way to you may look another way to another. Moreover, what may look one way to you at one time, may look another way to you at another. Colors, tastes, smells, feels, etc., can all vary from observer to observer, and can vary in the same observer at different times. If this is right, then which perspective is privledge? And how do we account, on the naive view, for the fact that some people have got it wrong, if there is a priveledged perspective?

(3) Finally, in light of (1) and (2), how do we know for sure that there are these mind-independent objects out there?

So, to accommodate the above sorts of objects, we might modify our Theory of Perception to the following...

- The Not-so-Naive Theory of Perception (AKA: Indirect Realism)

"There's me, and the rest of the world, which I detect indirectly through my sensory organs. The rest of the world is independent from me; if I were to disappear, the rest of the world would still be here, and it would remain roughly as I thought it was. So why do I have the sensation of seeing typed words right now? Because there are typed words in front of me now, and they are causing me to have an idea of typed words. It is through this idea, then, that I have access to the typed words that exist out in the world. Consider the following diagram for clarification:

On this view, external objects are still

mind-independent. It's just that our access to them is mediated through

our ideas of them. We have images in our head, as it were, and it is

through these images that we get to figure out what is what in the

world. This is why this view is called indirect realism: our access to

mind-independent, external objects is indirect."

However, this view has several problems, which we went over in class, and which I will summarize briefly here:

(1) The relationship between external objects and ideas is incomprehensible. What sort of relationship would make sense in any case? How could we make sense of the relationship between external objects and our ideas? You might think that our ideas resemble or are simlar to or are like the external objects. Consider: How does a picture, a portrait, say, get to be about a particular somone? Well, first, the picture has to be like or resemble or be similar to the individual. In the above drawing, for example, I tried to show this by having the tree idea (the tree inside of the thought bubble) be somewhat similar to the external, mind-independent tree (the tree in front of the spikey-haired dude). But if this is right--if ideas get to represent or be about external things by being similar to them in the right sorts of way--then we run into a problem: we are only justified in thinking that two things are similar if we have experienced them both. If indirect realism is right, however, how do we know that our ideas are similar to external objects? According to this picture, the only access we have to external objects is by our ideas that we have of them. So we have no way to get at the external objects in order to confirm that these things are indeed similar to our ideas of them. It would be like claiming that a certain portrait represents a particular individual, Bob, who no one has actually ever seen. If no one has actually seen Bob, then how do we know that the picture looks like him at all? So the relation between external objects and ideas can't be one of similarity. But what other options are there? None that are coherent, says this line of argument.

(2) The veil of perception. Similar to the last objection, this one claims that there is, according to indirect realism, a perpetual veil of perception between us and things in the external world. We can never get at things directly, in other words, so how can we be sure that these things are even there? One answer might be: well, that there are external objects that are similar enough to our ideas is simply the best explanation for why we have the ideas that we do. Remember our explanation of the view: "why do I have the sensation of seeing typed words right now? Because there are typed words in front of me now, and they are causing me to have an idea of typed words. It is through this idea, then, that I have access to the typed words that exist out in the world." In response to this objection, however, is the following: the indirect realist has to at least admit that there are somtimes ideas that are not caused or connected to external objects. Just think of all the things that led the indirect realist to be an indirect realist in the first place--dreams, hallucinations, illusions, etc. Since the existence of external, mind-independent objects doesn't help explain why we have the ideas we do in these sorts of cases, why should we think it's any better of an explanation in other types of cases. Finally, just try to say--fill in the gritty details, that is--how it could be that an external, mind-independent thing causes or affects a mind-dependent idea. It's incoherent!

(3) Inconceivability Argument. Try to imagine something without imagining that you are there perceiving it. Go ahead. It's impossible. Everytime you try to imagine something, you have to imagine that you are looking in on the thing you've imagined--perceiving it from above, so to speak. This (supposedly) shows that objects do not exist independent of minds or ideas. [Incidentally, there's a problem with this argument. What is it?]

(4) Variability Argument. Recall problem (2) for Direct Realism: "What may look one way to you may look another way to another. Moreover, what may look one way to you at one time, may look another way to you at another. Colors, tastes, smells, feels, etc., can all vary from observer to observer, and can vary in the same observer at different times. If this is right, then which perspective is privledge? And how do we account, on the naive view, for the fact that some people have got it wrong, if there is such a priveledged perspective?" Notice that this isn't just a problem for colors, tastes, smells, etc., but it also seems to be the same with shapes, extension, texture, solidity, motion, etc. What may look smooth far away, may look jagged close-up; what is small far away may be large close-up; what is oblong from one perspective, can be perfectly round from another; what moves fast to one, can move slow to another, etc. In other words, it seems that all properties can vary from observer to observer, or from one time to another in the same observer. But if this is right, and if none of these perspectives is privledged, then what's left for external objects to be?

So, to accommodate the above sorts of objects, we might modify our Theory of Perception to the following...

- The Not-so-Naive but Totally Crazy Theory of Perception (AKA: Idealism)

So, on this view, things would 'disappear' if there weren't any mind to perceive it. Although this is sort of the wrong way of looking at it, since there are no objects 'out there' to disappear. Moreover, if there is a mind that perceives everything all of the time--perhaps God, say--then things wouldn't 'disappear' in any sense.

However, you might wonder whether, like direct realism, idealism can make any sense of the distinction between 'veridical' ideas and 'illusory' ones. Even the idealist has to admit that certain ideas, such as the one of you reading a string of words right now, are more vivid, steady, distinct, and orderly, than other ideas, such as the one you have when you have the idea of a watery image on hot asphalt. Also, some ideas are voluntary (as when you purposely look at the sun and then look away and see an orangey-red after image), while others are involuntary (as when you are reading the flow of these typed words right now). Can there be a distinction, then, on this view between 'dreams' and 'reality', for example?

Discussion pending...

Note: The summary above is very quick, dirty, and incomplete. For elaboration, and a more accurate representation of the views I've outlined, see the following helpful internet resources:

- The

Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy's entry on Locke, Berkeley and

(in particular) The

Problem of Perception.

Page Last Updated: Sept.

17, 2008