Course Management Sites

General Student Resources

Useful On-Line Library Resources

Important Museum Sources

American Association of Museums

Association of Art Museum Directors

Association of Science-Technology Centers

Group for Education in Museums

Institute of Museum and Library Services

International Council of Museums

Visual Understanding in Education

------

Museums On-line (1,700 Museums)

Museums in the USA (1,000+ web listings)

-----

Children's Museum of Cleveland

Cleveland Museum of Natural History

Dittrick Medical History Museum

National Inventors Hall of Fame

Oberlin Improvement and Historical Association

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum

Western Reserve Historical Association

-----

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archeology (Oxford)

National Museum of American Art

National Museum of American History

National Museum of the American Indian

National Women's History Museum

Peabody Museum of Natural History (Yale)

General Sources on History

Books Recommended for Purchase

History

312

Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge

Spring 2003

Mr. VolkRice 309, x8522Office Hours: Monday 1-2 PM; Tuesday, 11-12 AM ; Wednesday, 10-11 AM and by appointment

Reading

You are expected to do the reading, and to complete it in a timely manner (i.e., prior to the meeting of the class). There is a substantial reading load and so I strongly recommend that you form into 3-4 person reading-groups. You are welcome and encouraged to split up the reading within the group as long as each reader has an opportunity to report back to the group of the material that he/she has read.

Museum Visits

Museum visits are planned around most weekly assignments. We will discuss at the first class how we will schedule off-campus visits. It is possible that not everyone will be able to visit every site, but the expectation is that you will make most of the visits. (I will help you understand what "most" means during our first class.) Museum visits and information related to the visits will be posted under the "Announcements" section of Blackboard.

Requirements and Grading

(1) Weekly Assignments:

Four students will be in charge of each class session. Two of the four will write a short (3-5 page) paper suggesting some basic analytic and/or historiographic issues raised in that week's readings. I will provide some guidance for these papers in terms of the questions to be asked. These two are responsible for posting the papers to the “Blackboard” system by the Tuesday afternoon (no later than 6:00 PM) prior to each Wednesday evening's class at which point we will all discuss the readings.The other two students will serve as respondents to the papers, summarizing the main points of the assigned paper and starting the general discussion. All the other members of the class are required to bring discussion questions to class based on their reading. I will collect these questions at the beginning of class. The number of times that you will each be assigned to write papers and serve as a respondent will depend on the total number of students in the course, but, generally speaking, you will likely be responsible for writing papers for two classes and serving as a respondent for an additional two classes. During the first class, we will assign responsibilities as well as grading options for these papers. I will provide written feedback on all papers; respondents will get a check+, check, or check- as a grade.

(2) Museum Critiques (two) Information on the writing of museum critiques will be handed out at the start of class and will be based on "Visiting the Museum: Some things to think about in general and in writing your critiques." First critique due March 5; second critique due April 9.

(3) Final Project

A final museum-design project (don't worry - technical expertise not required). Proposal due April 2; Bibliography/resources due April 23; Final project due by May 13, with possible extension (with my approval) to May 15. No extensions beyond that date without an official incomplete.

(4) Participation. Class participation is essential and will be reflected in your grade. I understand that not everyone finds it as easy to participate actively, but this is a small class with a lot of interesting things happening. As very bright people, I'm confident that you'll all have wonderful things to contribute to the course. If you feel that something is preventing your full and eager participation in the course, please see me and we will try to sort it out.

20% Comments: 2 x 5% each 10% Museum Critiques: 2 x 10% each 20% Final Project 25% 25%

A Note on the Readings:

All books recommended for purchase should be available at the Oberlin College bookstore (or through on-line booksellers). These books will also be on reserve in the library. The other materials are collected into a course pack which will be available for purchase through the History Department. Two copies of the course pack will also be on reserve in the library. Those articles in the course pack are noted with an * in the syllabus. Furthermore, the articles in the course pack will also be available on the Electronic Reserve (ERes) system.

Museum Sites on the Web

There are probably thousands of museum sites on the web. I have listed a few sites devoted to museum associations, meta-sites on museums, local area museums, and a brief list of a few of my favorites. Feel free to give me your own, and I'll add them. The listing is only available on the on-line syllabus.

Books Recommended for Purchase:

Stephen T. Asma, Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums (New York: Oxford University Press), April 2001.

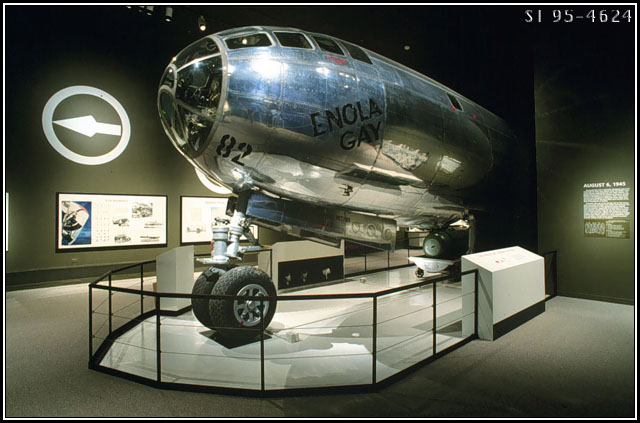

Steven C. Dubin, Displays of Power: Controversy in the American Museum from the Enola Gay to Sensation (New York: New York University Press), Dec. 2000.Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures. The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display (Washington and London: Smithsonian Press), 1991.

Stephen E. Weil, Making Museums Matter (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press), 2002.

Lawrence Weschler, Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder. Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Marvels of Jurassic Technology (New York: Vintage Books), 1996.

"Aztecs" (Royal Academy of Arts, London)

February 5: "The Primary Function of Any Museum Is…"

Introduction. What is a Museum?

James A. Boon, "Why Museums Make Me Sad," in Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures. The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display (Washington and London: Smithsonian Press, 1991), pp. 255-277. [NOTE: This is a good essay to read both at the beginning and the ending of the course. In its style, almost more than in its content, it mimics the museum and the process of museum going. Read it first, without stopping to "figure everything out." Then return to it at the end of the course and see what you make of it.]

*Sharon Macdonald, "Introduction," in Theorizing Museums. Representing Identity and Diversity in a Changing World, ed. Sharon Macdonald and Gordon Fyfe (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), pp. 1-18. [* means that the article is on Electronic Reserve -- ERes]

*Carol Duncan, "The Art Museum as Ritual," in Civilizing Rituals. Inside Public Art Museums (London and NY: Routledge, 1995), pp. 7-20. [ERes]

*Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, "What is a Museum?" in Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), pp. 1-22. [ERes]

February 12: Wonderment and the Museum Purpose. Collections, Collecting,

Organizing.

*Jorge Luis Borges, "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius," in Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), pp. 68-81. [ERes]

Stephen Greenblatt, "Resonance and Wonder," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 42-56.

*Susan M. Pearce, "Collecting: Shaping the World," in Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1992), pp. 68-88, and "Museums, the Intellectual Rationale," (pp. 89-117). [ERes]

*D.H. Lawrence, "Things," The Complete Short Stories, Vol. III (London: Heinemann, 1955), pp. 844-853. [ERes]

Stephen T. Asma, Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums (New York: Oxford University Press), 2001. (Begin)

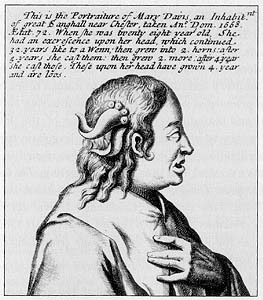

The horn of Mary Davis of Saughall (Museum of Jurassic Technology)

Virtual Visits:

February 19: Museums, the Rise of Modernity, and the Creation of the Public Sphere

In this section we will explore the relationship of the museum to modernity - in particular we want to explore the relationship of museums to the notion of public space, both its historical creation and its specific location in the late-18th and 19th century. We will focus on department stores, the press, fairs, and circuses. We also want to examine the promise of museums as related to their location in political modernity: democratic representation (both in the museum and in terms of museum goers). The readings set these issues out theoretically (Habermas) - and you are encouraged to read that first - and historically (Wallach). Pearce explores the various impulses behind collecting (leading to different types of museums or collections) and offers a brief overview of the history of museum collections. Lawrence is, well, fun.

*Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991 [1962]), pp. 27-51, 57-67. [ERes]

Stephen T. Asma, Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads, (complete).

*Kevin Walsh, "The Idea of Modernity," The Representation of the Past: Museums and Heritage in the Post-Modern World (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), pp. 7-38. [ERes]

Recommended: *Tony Bennett, "Museums and Progress. Narrative, Ideology, Performance," in The Birth of the Museum. History, Theory, Politics (London and NY: Routledge, 1995), pp. 177-209. [ERes]

Museum Visit:

Wednesday, Feb. 19: Natural History Museum (Cleveland): Leave Oberlin approx. 5:30, dinner at "Mi Pueblo," then museum.

Virtual Visits:

Harrods. The approach here is to look for similarities and differences between the museum and the department store, two early public spaces. Consider the interactions between spectacle, display, consumption, and acquisition. You might be particularly interested in visiting the lingerie department or ladies accessories. If you were in London, I would have you visit the "Egyptian Room." What is the department store "look" vs. the museum "look," and what is the visitor's gaze at each?

February 26: Museum and Modernity I: Museum Design - Ways of Narrating, Ways of Seeing

Two main issues need to be discussed in

this section, both of which build off the idea of the museum as a product

of modernity: (1) The idea of the museum as a narrative structure. (Roberts)

Much like a novel (itself a 19th century phenomenon) or a nation, the

museum is a narrative structure which is fundamentally implicated in interpretation.

(2) The design and space of the (modern) museum is bound up with its existence

as a public space. (Bennett) In that sense it is expected to be open to

publics at the same time that

it is concerned both with how the publics will behave in museums and how

they will use the museum. We will explore these issues in terms of the

design of the interior museum space (rather than its external architecture),

and as relates to the transmission of certain "privileged" forms

of knowledge, science (Macdonald)

*Lisa C. Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative. Educators and the Changing Museum (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997), pp. 56-67, 131-150. [ERes]

Svetlana Alpers, "The Museum as a Way of Seeing," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 25-32.

*Tony Bennett, "The Exhibitionary Complex," in David Boswell and Jessica Evans, Representing the Nation: A Reader. Histories, Heritage and Museums (London and New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. 332-361. [First published in New Formations 4 (1988): 73-102][ERes]

*Susan M. Pearce, "Meaningful Exhibition: Knowledge Displayed," in Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study (Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1992), pp. 136-143. [ERes]

*Sharon Macdonald, "Exhibitions of Power and Powers of Exhibition. An Introduction to the Politics of Display," in Sharon Macdonald, ed., The Politics of Display: Museums, Sciences, Culture (London & NY: Routledge, 1998), pp. 1-17 (only). [ERes]

Museum Visit:

March 1: Cleveland Museum of Art (Meet at 1:00 to drive in)

Virtual Visits:

There are literally hundreds of possibilities. You might try:

Walker Art Center (Minneapolis) (Take a look at the Michelangelo Pistoletto exhibit)

First Museum Critique Due March 5 (turn in during class)

March 5: Museums and Modernity II: Museums and the Nation

*Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach, "The Universal Survey Museum," Art History 3:4 (December 1980): 448-469. [ERes]

*Bluford Adams, "Barnum's Long Arms: The American Museum," in E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman & the Making of U.S. Popular Culture (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), pp. 75-115. [ERes]

*Alan Wallach, "William Wilson Corcoran's Failed National Gallery," Exhibiting Contradiction: Essays on the Art Museum in the United States (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998), pp. 22-37. [ERes]

Teresa Meade, "Holding the Junta Accountable: Chile's 'Sitios de Memoria' and the History of Torture, Disappearance, and Death," Radical History Review 79 (winter 2001): 123-139.

No Museum Visit

Virtual Visits

Again, hundreds of possibilities. Consider those particular museum sites that carry the burden of delivering a national message, either in the direct sense (e.g. the National Museum of American History), as a showcase of the nation (the "universal survey museum", of which the Louvre is the first), or attempt to influence the discourse as to what values should be represented in the national past/present (e.g. the National Civil Rights Museum). Others:

We have defined three broad purposes for the museum (used here in its widest context): (1) education; (2) aesthetic/visual enjoyment and pleasure; and (3) entertainment. In its modern context, the vast majority of museums see their primary task as educational. This week we will explore questions of learning theory and how new theories of learning have impacted the design of museums.

*Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, "Learning from Learning Theory in Museums," The Educational Role of the Museum, ed. Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, 2nd ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. 137-145. [ERes]

*George E. Hein, "Educational Theory," in Learning in the Museum (London and New York: Routledge, 1998), pp. 14-40. [ERes]*Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Kim Hermanson, "Intrinsic Motivation in Museums: Why Does One Want to Learn?" in Hooper-Greenhill, The Educational Role of the Museum, pp. 146-160. [ERes]

*Helen Coxall, "Museum Text as Mediated Message," in Hooper-Greenhill, The Educational Role of the Museum, pp. 215-222. [ERes]

*Kirsten M. Ellenbogen, "Museums in Family Life: An Ethnographic Case Study," in Gaea Leinhardt, Kevin Crowley, and Karen Knutson, eds., Learning Conversations in Museums (Mahwah, NJ and London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002), pp. 81-101. [ERes]

Other resources:

John H. Falk and Lynn D. Dierking, Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning (Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press), 2000.

Gaea Leinhardt, Kevin Crowley, and Karen Knutson, eds., Learning Conversations in Museums (Mahwah, NJ and London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 2002.

Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and Their Visitors (London: Routledge), 1994.

Baseball centers around the (seemingly) eternal struggle between pitcher and batter, and each uses physics, albeit intuitively, to gain a slim advantage over the other in determining the fate of the game's center of interest -- the ball.

(From a current exhibit at the Exploratorium on the physics of baseball)

Museum Visit

March 15: Great Lakes Science Center (Meet at 1:00 PM for drive into Cleveland)

Virtual Visits

Exploratorium (San Francisco)

Children's Museum (Boston)

Museum of Science & Industry (Chicago)

March 19: Material Culture and the Production of Historical Narratives. Artifacts, Authenticity, Truth

A particular modernist assumption is that museums, by providing their visitors with the artifact, present them not just with "the real thing," but with the truth. Thus, the museum is about "truthful"objects and "accurate" messages. Weschler, and David Wilson, remind us that museums do not always serve these purposes… or do they? Wallach notes that authenticity and originality are not always the same thing.

Lawrence Weschler, Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder. Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Marvels of Jurassic Technology (New York: Pantheon), 1995.

*Alan Wallach, "The American Cast Museum: An Episode in the History of the Institutional Definition of Art," in Exhibiting Contradiction. Essays on the Art Museum in the United States, pp. 38-56. [ERes]

Spencer R. Crew and James E. Sims, "Locating Authenticity: Fragments of a Dialogue," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 159-175.

NOTE: For those intrigued by the Museum of Jurassic Technology, the MJT has just published its own "Jubilee Catalog," The Museum of Jurassic Technology, listed as authored by "The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Information" in 2002. The slim book describes (but doesn't analyze) the exhibits in the museum. This is not the "real" story of the museum (which is encountered in Weschler), but the museum's own presentation.

Recommended: *Susan A. Crane, "Curious Cabinets and Imaginary Museums," in Museums and Memory, Susan A. Crane, ed. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000), pp. 60-80 and The Museum of Jurassic Technology, "Geoffrey Sonnabend: Obliscence: Theories of Forgetting and the Problem of Matter: An Encapsulation by Valentine Worth," in Crane, ed., Museums and Memory, pp. 81-90. [ERes]

Miles Orvell, The Real Thing : Imitation and Authenticity in American culture, 1880-1940 (Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press), 1989.

No Museum Visit Scheduled: Try to visit museums over spring break!

Virtual Visits

March 26: Spring Break

April 2: Museums, Memory and History

In general, the objects preserved in museums are solid (i.e., three dimensional) and originate in the past, so that the observer experiencing them in three-dimensional space must somehow also cross a temporal barrier. In this sense alone, then, museums are not the same as, say, illustrated books. But if we recognize this difference, we also need to raise some basic questions about how museums (fundamentally non-art museums, in this context) work. The questions we confront have to do with what is "real," what is "authentic" (and, in that sense, we can also be dealing with art and the question of forgeries), and how we relate to "old" three-dimensional objects. Do objects have meaning sui generis? What role do museums have in terms of mediating experiences? In this week, we the explore the relationship of material culture (the artifact) to "truth," "reality," or "authenticity," and the specific set of questions which are raised for institutions which choose to preserve and promote material culture.

The readings all involve objects (artifacts) and their meanings - the relationship between artifact and meaning. Radley treats the way in which we perceive objects in a social psychological way. Both Crew and Sims and Pearce, on the other hand, suggest how historical study gives meaning to material culture and how our possession of objects for the human past influences the way in which we understand the past. The Mamet script is a playful approach to all the questions of "reality" within a museum context.

*Susan M. Pearce, "Meaning in History," in Museum, Object, and Collection: A Cultural Study (Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1992), pp. 192-209. [ERes]

*John Urry, "How Societies Remember the Past," in Theorizing Museums. Representing Identity and Diversity in a Changing World, Macdonald and Fyfe, eds., pp. 45-65. [ERes]

*Alan Radley, "Boredom, Fascination and Mortality: Reflections Upon the Experience of Museum Visiting," in Gaynor Kavanagh, ed., Museum Languages: Objects and Texts (Leicester, London and NY: Leicester University Press, 1991), pp. 65-82. [ERes]

*Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative, pp. 88-103. [ERes]

*David Mamet, "The Museum of Science and Industry Story," in Five Television Plays (New York Grove Weidenfeld, 1990), pp. 91-125. [ERes]

*Gaynor Kavanagh, "Dream Spaces, Memories and Museums," in Dream Spaces: Memory and Museum (London & New York: Leicester University Press, 2000), pp. 1-8. [ERes]

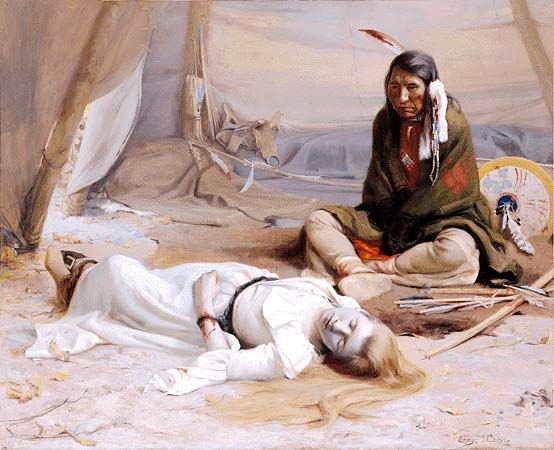

"The Captive," Eanger Irving Couse (1891), Phoenix Art Museum

Recommended:

*Raphael Samuel, "Preface: Memory Work," and "Unofficial Knowledge," in Theatres of Memory (London: Verso, 1994), pp. vii-xiii; 3-48. [ERes]

*David Glassberg, "Public History and the Study of Memory," The Public Historian 18: 2 (Spring 1996), pp. 7-22. [ERes]

*"Roundtable: Responses to David Glassberg's 'Public History and the Study of Memory,'" with responses by David Lowenthal, Edward T. Linenthal, Michael Kammen, Linda Shopes, Jo Blatti, Robert R. Archibald, Barbara Franco, and David Glassberg, The Public Historian 19:2 (Spring 1997), pp. 30-72. [ERes]

Museum Visit (Tentative):

April 5: Youngstown Historical Center of Industry & Labor

Virtual Visits:

Transatlantic Slavery: Against Human Dignity (National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, Liverpool, UK)

Ironbridge Gorge Museums (Ironbridge Gorge, UK)

Tate Britain (London)

Second Museum Critique Due April 9 (turn in during class)

April 9: Culture Wars. The Battle to Shape Social Memory

The authority of museums to create interpretations

is challenged today as never before both by the visiting public and museum

professionals. Because museums are central public institutions that mediate

culture for growing numbers of people, they have become ground zero of

"culture wars" in many countries, particularly the United States

and, to a certain extent, Britain. Museum curators, museologists, and

students of museum practice now read the names of specific exhibits as

if they were battles sites from major wars: Harlem on My Mind (Metropolitan

Museum of Art, 1969), The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of

the Frontier, 1820-1920 (National Museum

of American Art, 1991); Sigmund Freud: Conflict and Culture (Library

of Congress, 1998), Birth and Breeding: the Politics of Reproduction

in Modern Britain (Wellcome Institute,

1993-4). For most observers, the most impressive battle of this war

was the Enola Gay exhibit (originally titled The Crossroads: The End of

World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War) that was

to open at the Smithsonian's National

Air and Space Museum in the mid-1990s. All our readings this week

concern this exhibit, and we will want to examine a number of issues.

Why are museums becoming such critical spaces for "culture wars"?

The museum's obligations of interpretation or, as one curator puts it:

"Why not take sides? Why not be partial? How can we possibly understand

the issues involved, when the whole point of history is being systematically

denied?" A reasonable assessment, but how does this play out at publicly

funded museums, particularly those thought to be representative of the

"nation" as a whole? How can museum curators prepare their defenses

for seemingly inevitable attacks?

*Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative, pp. 72-79. [ERes]

Steven C. Dubin, Displays of Power: Controversy in the American Museum from the Enola Gay to Sensation (New York: New York University Press, 2000), Chapters 1, 5, 6. Then pick either 2, 3, or 4. (Or, feel free to read the entire book!)

For a spectacular web site on the Enola Gay controversy, consult Edward J. Gallagher, Lehigh University: http://www.lehigh.edu/~ineng/enola/

Remains of the "Enola Gay," National Space and Air Museum, Smithsonian

Guest Visitor: Barbara Clark Smith (Curator, Division of Social History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian)

Museum Visit (Tentative):

April 12: Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and Museum

Virtual Visits:

April 16: Museums and the Ethnographic Other

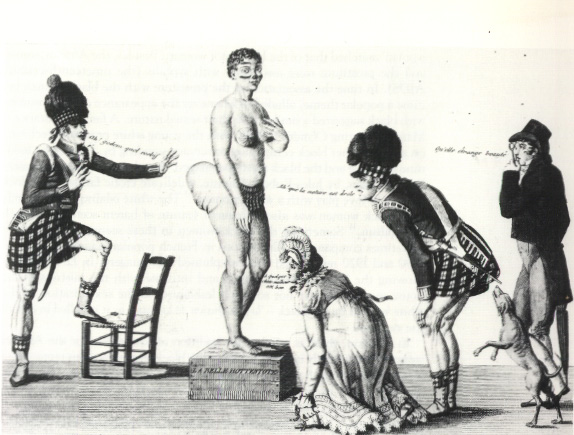

Here we look at the importance of the museum in its binary creation of the Other. The question to be examined is how a particular artifact/people/culture/time becomes available to an unfamiliar people. The exoticization of the unfamiliar (i.e., its separation from a presumed familiar) is often mediated by specific ideological institutions among which museums are central. Dias' focuses on the process of constituting racial difference, arguing that it is associated with the ways in which race is visualized and suggesting that anthropological collections and museums were important "systems of evidence" in the conceptualization of racial difference. An important issue here is the fact that this process seems to be accomplished by liberals and social reformers, not reactionaries, and that we must be aware of the museum as a "democratic" space, open to the public, when we understand the ideological role which it played in the 19th century (and now).

*Tracy Lang Teslow, "Reifying Race: Science and Race at the Field Museum of Natural History," in MacDonald, ed., The Politics of Display, pp. 53-76. [ERes]

Various articles from Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, including: Michael Baxandall, "Exhibiting Intention: Some Preconditions of the Visual Display of Culturally Purposeful Objects," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 33-41.

"La Belle Hottentot," French Print

Museum Visit:

April 19: Allen Memorial Museum of Art

Virtual Visits:

Pitt Rivers Museum (Oxford)

Ashmolean Museum of Art & Archeology (Oxford)

American Museum of Natural History (New York)

April 23: Museums and the The Human Subject

*Stephen Jay Gould, "The Hottentot Venus", in The Flamingo's Smile: Reflections in Natural History (NY: W.W. Norton & Co, 1985), pp. 291-301. [ERes]

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, "Objects of Ethnography," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 386-416 (only).

*Paul Greenhalgh, "Human Showcases," Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World's Fairs, 1851-1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), pp. 82-111. [ERes]

No Museum Visit

Virtual Visits:

Mutter Museum (You might want to visit the exhibit on "The Social History of Conjoined Twins")

Famous Freaks (A web site with no pretense of being a museum, nonetheless suggests that "freaks" are still an object of the museum gaze)

April 30: Museum Projects Presentations: Making Museums Matter

Stephen E. Weil, Making Museums Matter (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press), 2002. [Pages to be assigned]

May 7: Museum Projects Presentations

Optional Readings for April 30 and May 7: We have focused almost exclusively on the historic museum, particularly in the 19th century, the moment of its greatest impact and importance. At one level, it is not hard to critique museums and museum practices in the way in which they solidify discourses about difference, hierarchy, and power. But the museum (or theme park or heritage site, etc.) remains an important, even vibrant institution which can offer its visitors new insights and which can destabilize the very discourses that museums have created in the past. The articles this week offer suggestions, from the curators' viewpoint, as to how this can be accomplished. Gurian wonders how best to design exhibits that can help people learn and realizes that curators must work against the discipline that has taught them what "appropriate behavior" in museums is. Vogel argues that museums always "recontextualize and interpret objects," and one should not apologize for this. Rather, by discussing specific exhibits, she suggests how curators must be "self-aware and open about the degree of subjectivity" in their collections. Using a somewhat thicker theoretical approach, Porter explores the ways in which museums constitute masculine and feminine and then describes a series of contemporary exhibits in Britain and northern Europe that challenge conventional readings. And Jones suggests how exhibitionary practices can rework the British colonial legacy. The exhibits discussed in these articles are just a few of many (see the optional reading for this week for more) which have been mounted in the past decade that suggest that the museum and its related exhibitionary institutions remain very much engaged in a struggle over how knowledge is to be shaped.

Elaine Heumann Gurian, "Noodling Around with Exhibition Opportunities,"

in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 176-190.

Susan Vogel, "Always True to the Object, in Our Fashion," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 191-204.

*Ivan Karp, Christine Mullen Kreamer, and Steven D. Lavine, eds., Museums and Communities. The Politics of Public Culture (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press), 1992. See, in particular, Jane Peirson Jones, "The Colonial Legacy and the Community: The Gallery 33 Project," pp. 221-241. [ERes]