Course Management Sites

General Student Resources

News Sources on Latin America

General Sources on History

Books Recommended for Purchase

Maps

Mexico

Morelos

History

365

Peasants, the State and Rebellion in Mexico

Fall 2002

Mr. VolkRice 309, x8522Office Hours: Monday 1-2 PM; Tuesday, 11-12

AM ; Wednesday, 10-11 am.

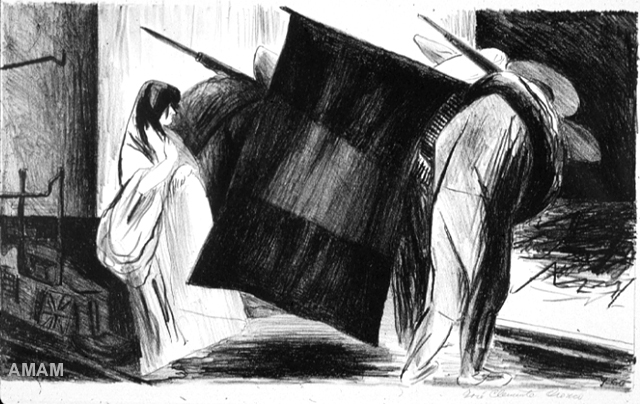

Jose Clemente Orozco, The Flag (Allen Memorial Art Museum)

The purpose of this course is the in-depth investigation of the manner in which subaltern populations, peasants in this case, influence, impact, or otherwise have an effect upon a state which they do not control, and the manner in which historians go about studying this process. Since rebellion is the most common (but not only) vehicle by which peasants hope to impact state behaviors, we will focus on moments of rebellion. While I will argue that subalterns can have an impact outside of their local settings, not all the authors we will read share that opinion, and some strongly disagree.

Our tasks include reaching a clear understanding of the principal terms that we employ in this specific historical field (particularly “peasants,” the “state,”“hegemony,” etc.), exploring our assumptions about rural populations and their ability to shape a political sphere which is most often formally determined in urban (“modern”) settings, and developing a theoretically informed methodology which can guide our analysis of these issues.

Although there are abundant examples of peasant rebellion throughout Latin America, and from pre-colonial to modern times, we will only examine rural populations in Mexico from the early nineteenth century to the present. There are two primary reasons for this: (1) While we can develop some general arguments about subaltern politics, our best analyses need to be historically grounded and contextualized. We can do that better if we concentrate on only one social formation (Mexico) as opposed to jumping from one country to another. (2) Beyond a doubt, Mexico has given rise to the most sophisticated (and most exciting, in my opinion) historiography, a good portion of which is available both in English and (even) in paperback! There are similar reasons for staying in the post-independence period, and we will explore these further in class.

Requirements and Grading

Your final project will be a 10-15 page paper (or equivalent project) on any topic covered in the course. You will need to clear the final topic with me by November 18. The project is due on December 16 (the last day of reading period), although you may receive an extension (if requested) until December 20, the time scheduled for seminar exams (although there will not be a final examination in this seminar). All projects submitted between Dec. 16 (at 4:30 PM) and December 20 will be graded down one grade-step per day unless you have requested and received an extension from me. All projects submitted after 2:00 PM on December 20 will not be graded unless you have received an official incomplete in the course. If you choose to present a final project in a format other than a paper, you will need to clear that with me.

I expect all written work to be thoughtful, well constructed, and spell-checked! An advanced warning: computers always seem to go down just when you are putting in your final paragraph. Always save your material frequently to a floppy, not to the hard disk. If the computer crashes, at worst you will only lose a few paragraphs. So don't tell me that the computer ate your paper.Final GradeYour final grade will be based on your weekly written work, the quality of your work as a respondent, your final project (30%) and your class participation (20%). I don't expect everyone to understand fully all of the reading; I do expect you to raise questions when you don't understand.

Work at Oberlin is governed by an Honor Code. If you are unclear what that entails, please consult the information at the Honor Code site.ACCESSING THE COURSE: Course materials can be found on the “ CourseInfo” Blackboard system. This electronic bulletin board will post all the outlines for the course lectures, the syllabus, exams and paper assignments, and other materials useful for the course. You must register to get into the system, and I will provide information on how to do this and how to use the system in the first week of classes. In the meantime, click the following for information on accessing Blackboard. Once you are registered, you enter via a password, and then can locate daily outlines, assignments or other useful information. It is important that everyone registers for the CourseInfo Blackboard system as it provides me with an easy way to email the class.

SOURCES ON LATIN AMERICA: I have compiled a great many internet sources and resources on Latin America at Sources and Resources on Latin America. This resource includes a variety of materials from the history of Latin America to organizations and publications of interest to activists working on Latin American issues.

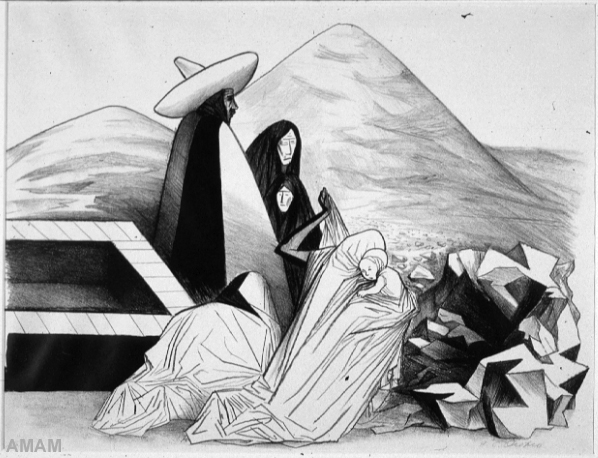

(Jose Clemente Orozco, Mexican Landscape, Allen Memorial Art Museum)

Books Recommended for Purchase

Florencia Mallon, Peasant and Nation: The Making of Postcolonial Mexico and Peru (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994).

John Womack, Jr., Zapata and the Mexican Revolution (New York: Random House), 1970.

Samuel Brunk, Emiliano Zapata! Revolution and Betrayal in Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press), 1995.

Mariano Azuela, Los de Abajo (New York: Signet), 1996 reissue.

Subcomandante Marcos, Leslie Lopez (translator), Frank Bardacke, Shadows of Tender Fury: The Letters and Communiques of Subcomandante Marcos and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (New York: Monthly Review Press), 1995.

Howard Campbell, et al. eds., Zapotec struggles : histories, politics, and representations from Juchitán, Oaxaca (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press),1993. [NOTE: It is likely that this is out of print and you will need to buy it used from Amazon.com or another service, if you want to purchase it, or get it from Ohio LINK or the library.]

Jennie Purnell, Popular Movements and State Formation in Revolutionary Mexico: The Agraristas and Cristeros of Michoacán (Durham: Duke University Press), 1999.

NOTE: Course materials will be available in a variety of formats:

— All the books recommended for purchase are also available on reserve in Mudd. You can also request library copies of them via Ohio Link.

— Many of the articles which have been copied are available in hard copy on reserve in Mudd and on-line via the ERes system.

— Those articles noted as “JSTOR” are only available by the internet. They are a part of a full-text archive of scholarly journals. The easiest way to access these journals is via the on-line copy of this syllabus — they are linked directly to the article in question. These articles can be downloaded and/or printed directly from JSTOR.

Syllabus

September 9: Background on Mexican history (lecture/questions)

For you to study peasants in Mexican history, It is essential that you have a background knowledge of the broader history of Mexico. Many of the readings will provide this over the course of the semester, but this lecture, in particular, is designed for those of you unfamiliar with Mexico's history. Although it is not required, you might want to consult a standard textbook history such as Michael Meyer and William L. Sherman, The Course of Mexican History (New York: Oxford University Press), various editions, or Jaime Suchlicki, Mexico: from Montezuma to NAFTA, Chiapas, and Beyond (Washington: Brassey's), 1996.

You can also read the appropriate chapters in some survey texts of Latin American history. See, in particular, the latest editions of Mark A. Burkholder & Lyman L. Johnson, Colonial Latin America; David Bushnell and Neill Macaulay, The Emergence of Latin America in the Nineteenth Century, and Thomas Skidmore and Peter Smith, Modern Latin America, all published by Oxford University Press.

See also: Mexican History, 1810-1940: A Chronological Summary of the Main Events and Developments

You can also read the useful section titled, “The Mexican Revolution,” skipping the introduction and focusing on “The Insurgency” and Caudillo Politics and the Liberal Reform”.

I: Theory

Week of Sept. 16 (reschedule date): Can the Subaltern Speak? Some theoretical approaches to “subalterns” and the peasantry.

Reading: Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Subaltern Studies: Deconstructing Historiography,” Subaltern Studies IV (1985): 330-363. [ERes]

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Marxism and The Interpretation of Culture, Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, eds. (London: Macmillan, 1988), pp. 271-313. [ERes]

Ranajit Guha, “Small Voice of History,” Subaltern Studies IX (1996): 1-12. [ERes]

Peasant Social Worlds and Their Transformation: This is an interesting site directed and designed by John Gledhill for the University of Manchester (UK) Department of Social Anthropology and the ERA Consortium. When you open it up, you'll be asked to fill out your name and affiliation and email (if you want), then you can go to the texts. Within the site, you'll want to read:

Peasant Reproduction and Capitalism: Read “Theoretical Perspectives.” Follow the links (“Next Page”) through Marx and Lenin, the Chayanovian Alternative, and “Beyond the Classical Debates” (the last page is “Rural Futures”). You may also want to look at the section on “Anthropologists and the Peasantry,” particularly, “Why did anthropologists get interested in the peasantry?”

II: “Prehistory"

September 23: The Hidalgo rebellions and the early 19th century.

Reading: Peter Guardino, “Barbarism or Republican Law? Guerrero's Peasants and National Politics, 1820-1846,” Hispanic American Historical Review 75:2 (1995): 185-213. [JSTOR]

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Angustia

John Tutino, “The Revolution in Mexican Independence: Insurgency and the Renegotiation of Property, Production, and Patriarchy in the Bajio, 1800-1855,” Hispanic American Historical Review 78:3 (1998): 367-418. [JSTOR]

Eric Van Young, “Millennium on the Northern Marches: The Mad Messiah of Durango and Popular Rebellion in Mexico, 1800-1815,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 28:3 (1986): 385-413. [JSTOR]

September 30: The Reform Wars of Mid-Century

Reading: Florencia Mallon, Peasant and Nation: The Making of Postcolonial Mexico and Peru (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press), 1994.III: History — The Mexican Revolution

October 7: Background and Approaches

Reading: Mary Kay Vaughan, “Cultural Approaches to Peasant Politics in the Mexican Revolution,” Hispanic American Historical Review (1999): 269-305. [JSTOR]

The Mexican Revolution (University of Manchester site): Read “Introduction,” skip the next two sections ( “Insurgency” and “Caudillo Politics and the Liberal Reform”), then read “The Porfiriato,” and “Agrarian Revolution”.

Mariano Azuela, Los de Abajo (New York: Signet), 1996 reissue.Recommended (but not required) background reading:

Michael J. Gonzales, The Mexican Revolution, 1910-1940 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press), 2002.

October 14: Zapata (1)Reading: John Womack, Jr., Zapata and the Mexican Revolution (New York: Random House), 1970.October 28: Zapata (2)Reading: Samuel Brunk, Emiliano Zapata! Revolution and Betrayal in Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press), 1995.

Diego Rivera, Zapata (Martin Art Gallery)

November 4: Constructing the Revolutionary Image (3)Reading: Samuel Brunk, “Remembering Emiliano Zapata: Three Moments in the Posthumous Career of the Martyr of Chinameca,” Hispanic American Historical Review 78:3 (1998): 457-490. [JSTOR]

Preparation: You will be given some slides to consider for this week's class.November 11: Ideology

Reading: Plan de Ayala in English [Note: this document is also available in Spanish]

Corrido del Plan de Ayala: [Spanish only]

Michael W. Foley, “Organizing, Ideology, and Moral Suasion: Political Discourse and Action in a Mexican Town,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 32:3 (455-485) [JSTOR]

Judith Adler Hellman, “The Role of Ideology in Peasant Politics: Peasant Mobilization and Demobilization in the Laguna Region,” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 25 (1983): 3-29. [JSTOR]

Ana María Alonso, “U.S. Military Intervention, Revolutionary Mobilization, and Popular Ideology in the Chihuahuan Sierra, 1916-1917,” Daniel Nugent, ed., Rural Revolt in Mexico: U.S. Intervention and the Domain of Subaltern Politics, expanded ed. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), pp. 207-238. [ERes]IV: Post-history

Nov. 18: Topic for final project due during class

Nov. 18: Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s (The Cristero Revolt and Cardenas)Reading: Jennie Purnell, Popular Movements and State Formation in Revolutionary Mexico: The Agraristas and Cristeros of Michoacán (Durham: Duke University Press), 1999.

Marjorie Becker, “Black and White and Color: Cardenismo and the Search for a Campesino Ideology,”Comparative Studies in Society and History 29:3 (1987): 453-465. [JSTOR]Nov. 25: The Subaltern Voice?Reading: Howard Campbell, et al. eds., Zapotec struggles : histories, politics, and representations from Juchitán, Oaxaca (Washington : Smithsonian Institution Press),1993. [Note: limited editions available; buy used from Amazon or other seller.] Pages to be assigned.

Optional: Jeffrey W. Rubin, “COCEI in Juchitán: Grassroots Radicalism and Regional History,” Journal of Latin American Studies 26:1 (1994): 109-136. [JSTOR]

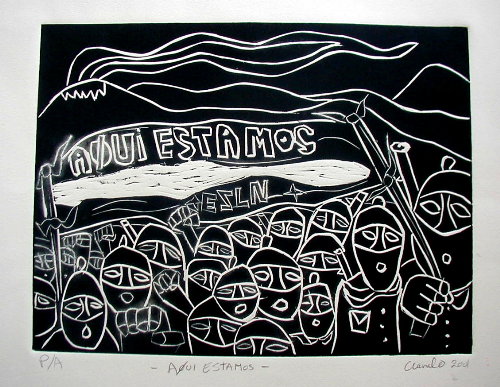

December 2: Modern ZapatismoReading: Subcomandante Marcos, Leslie Lopez (translator), Frank Bardacke, Shadows of Tender Fury: The Letters and Communiques of Subcomandante Marcos and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (New York: Monthly Review Press), 1995.December 16: Final project due.Note: This project is due on December 16 (the last day of reading period), although you may receive an extension (if requested) until December 20, the time scheduled for seminar exams (although there will not be a final examination in this seminar). All projects submitted between Dec. 16 (at 4:30 PM) and December 20 will be graded down one grade-step per day unless you have requested and received an extension from me. All projects submitted after 2:00 PM on December 20 will not be graded unless you have received an official incomplete in the course.

Films: The following films will be shown at scheduled times (which we will decide in the first week) over the course of the semester.

Alonso's Dream (2000; Danièle

Lacourse and Yvan Patry, dir.); 71 minutes.