Often the best plays strive to tackle difficult topics and emotions and raise questions which demand ample thought. Weldon Rising, a play by Phyllis Nagy which is running at the Little Theater this weekend, accomplishes both of these tasks very successfully.

Directed by senior theater major Sarah Rooney, the production takes great risks which contribute to the show's excellence.

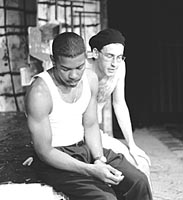

The plot revolves around the murder of Jimmy, played by junior Nicholas Sweeney, and the reactions of those who witness the crime. His lover Natty, played by senior Ben Esner, deals with the guilt and regret of his own cowardice.

The transvestite, Marcel, who was working the corner at the time, played by sophomore Lavell Blackwell, has his own issues of self and honesty with which to deal.

The lesbian couple who live in the same apartment building, Jaye and Tilly, played by junior Fedje Tangen-Donnelly and senior Lisa Ward, respectively, also work to make sense of the shocking violation of their safety and their responsibility to respond to witnessing the crime.

This play examines the actual stabbing of Jimmy as a hate crime committed by a passerby, played by Nathan Dore, and the response of each character in the aftermath.

The actors provide honest and committed roles as they draw the audience close to them with their emotional forwardness. The characters' responses to the crime, from refusing to deal with it to drinking the guilt away to self-hatred, run the gamut and provide diverse opportunities for audience sympathy. The characters are neither static nor completely consistent, which provides authenticity.

Set in the exaggerated heat of the hottest day of the year, with occasional radio announcements reminding viewers of the upwards of 180 degrees, the tension is great but not unbroken. Happily and surprisingly, this play which examines such heavy questions is able to keep itself from the mires of depression.

The characters deal with difficult problems but there is certainly comic relief in the frankness of both Tilly and Jaye and the suggestive stereotyping of Marcel. There are great lines and characterization in this play.

Although it might have been easier to take a more heavy-handed approach to the topic, the abruptness of language and unexpected humor effectively captivate viewers. Consequently, audience members are left with things to consider instead of a mere heavy, issue-laden plot.

The play is certainly not one for the squeamish, however. In the retelling of what happened and examination of the current situation, the crime is repeated multiple times, none of which cease to be upsetting. The recent murder of Matthew Shepard neither makes this action any easier to watch nor easier to listen to Dore's character talk about his act with apathy and chilling coldness.

The language of the play is abrupt and true to life, often involving some phrases that perhaps visiting parents could object to. Finally, if one is not bothered by the language or the violence, the viewer must accept considerable nudity in the end of the play. This is one of the obvious risks that Rooney and her actors have decided to take, and one which works.

The set works well with the plot in that it allows a crossing between settings for the characters, though this can be confusing. Parts of the action jump back and forth in time and blur what may be reality, creating an engaging unraveling of the story.

The only part of the show which may leave the viewer confused is the conclusion. What seems like a mostly realistic representation of an event throughout most of the play changes to a stranger, more confusing blurring of reality.

The impossible heat, with newsflashes of disintegrating bridges and melting busses, begins the trend and the ending pushes it further. While the ending does not hurt the play's power and courage, it may leave the audience wondering.

This can either help to emphasize the trouble the characters experience throughout the play or can complicate the ideas. The very end can be seen as more of a rebirth of sorts, as opposed to a total apocalypse. While neither choice neatly closes the play, the piece raises its share of questions, as any daring play hopes to accomplish.

The Kiss: Beth O'Brien (photo by Beth O'Brien)

Thespians: Junior Nicholas Sweeney and senior Ben Esner in Weldon Rising. (photo by Beth O'Brien)

Copyright © 1998, The Oberlin Review.

Volume 127, Number 8, November 6, 1998

Contact us with your comments and suggestions.